Bali is Indonesia’s window to the world. This role comes into full bloom with more and more global events taking place on the island, such as the the IMF and G20 summits. Whilst Bali participates in international affairs, on the other side of the coin, the world, too, participates in Bali’s affairs. In fact, Bali’s culture and philosophy provides lessons for the rest of the world, which quite often is in a state of war, be it in Ukraine, Yemen, the West Bank or otherwise.

This article was originally published in TIMELESS Bali Volume 2, an annual publication by NOW! Bali. Purchase your copy here:

Is Bali simply a venue for such struggles to be discussed? Or can it transmit to the participants of such influential gatherings a spirit of balance conveyed by its tradition? Has the inevitable meeting of this tradition with modernity generated a new sense of balance? Let us explore this idea further.

The Balinese have inherited a island of volcanoes, lakes and ash. The long-term historical endeavour has thus been to keep balance between themselves and the nature that surrounds them. While doing so, they have turned the island into one of the most fertile places on earth. They have literally “carved” it, creating a nature as much wild in its lush valleys and mountainous panoramas, as it is humanised in its forest temples and shimmering rice terraces.

This gargantuan effort to control the forces of nature needed an ideological support. This birthed the ancestor’s cult, linked to the ecology of the island. Humans are seen as “drops” of ancestral souls which dwell above the mountains. Their life unfurls in unending efforts to control the intangible forces that weighs over their daily life. The aim of the entire ritual system is to retain balance, through rites and offerings, between humans and these forces. If this balance is properly maintained, the soul, upon death, finds its way, again through rites, to the “old country” of its origin above the mountain, the ancestors’ abode, where it will wait for its next incarnation, down in Bali of course. This is the indigenous Balinese system at its core.

Through its contacts with India, which begun 2000 years ago, it became ‘Indianised’. The lords of the Indian cosmos were added to the ancestors and gods of the land from the local tradition. More recently, input from modern reformed Hinduism has clearly emphasised the notion of the Oneness of God (Sang Hyang Widhi), which enables Balinese Hinduism to find its place among the other religions of Indonesia.

Set on these dynamic foundations, Balinese culture has produced the stunning cultural beauty that has made it world-famous: colourful offerings of all shapes and sizes; dances to welcome the visits of the gods; fantastic cremation potlatches that reduces to flames colossal ritual towers symbolising the world, and more. With its natural beauty, cultural marvels and people’s smile, it is no surprise that, barely subjected to Dutch rule after a tragic war, in 1908, Bali appeared to its new lords as “paradise” and “abode of the gods”: instead of the spirit of hatred pulling Europe apart at the time, the Dutch found harmony and smiles all around. Ever since the 1920s, Bali has been one of the lights of the world.

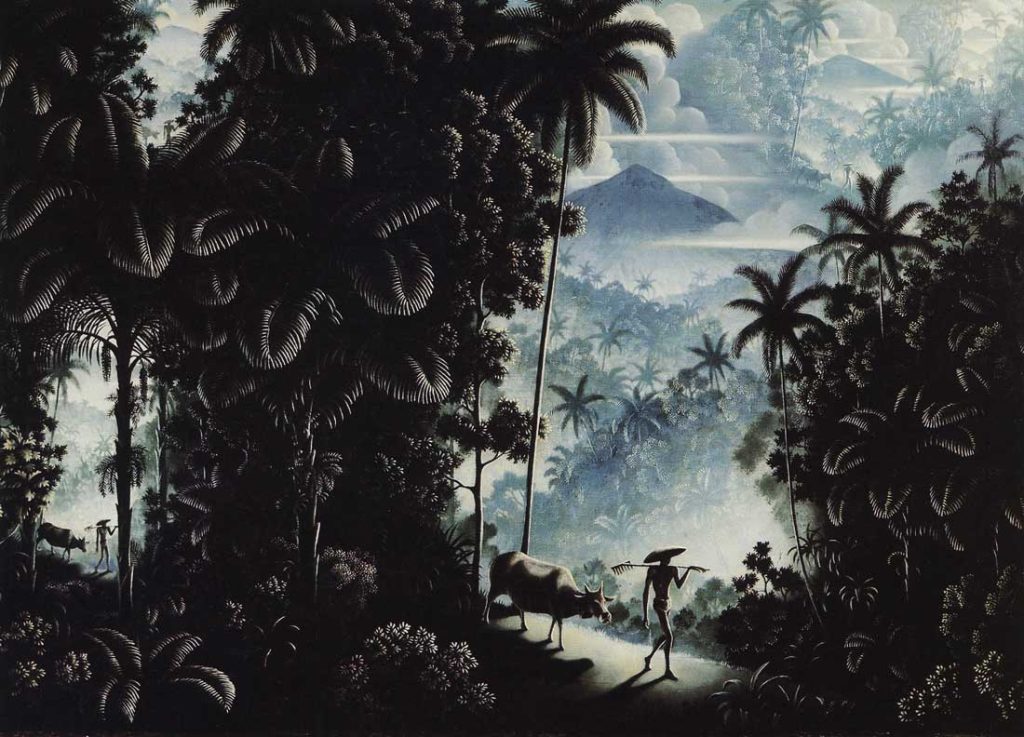

German artist Walter Spies was among the first foreign artists to have found inspiration in the peaceful ‘Dutch East Indies’, painting idyllic scenes of Bali that created a sense of wonder in Europe.

Bali has indeed had to cope with politics and societal change. It was not always easy. It has adopted Indonesian nationalism without trauma, other than the initial fight for Independence. The concept of nationalism, as put in the motto of Bhinneka Tunggal Ika, unity in diversity, and in the principles of the nation, the Pancasila, are in line with the deepest Balinese tradition: it underlines similarities rather than difference.

Bali has of course, after Independence suffered from the belief that society could be improved by whatever means, including violence, but it has recovered. It has restructured its Hindu tradition in a way that remains open, inventing in the process, based on village tradition, a “philosophy” of life, the Tri Hita Karana (the three causes of happiness in classical Kawi language). The Tri Hita Karana states as its goal the required harmony of humans with themselves, with nature and with the godly.

What is most interesting, however, is to see how artists have coped with change. How they have even defined it.

Village artists, heir to the great Balinese village tradition, have tended to depict themselves in an harmonious social and natural environment. While this may partially reflect the expectation of the market-exoticism, it also reflects, as explained above, the Balinese deep cultural yearning for harmony.

One finds the same quest for harmony in the main stream of Balinese modern art. After the Balinese intellectuals of the 1950s to the 1970s restructured Balinese religion in line with Hindu norms, most modern artists did the same with regard to visual art. They ‘Hinduised’ it. Some made artworks that symbolised, in a semi-abstract way, the Balinese conception of the Mandala (e.g. Pande Sukada). Others used geometric or semi-geometric symbols — dual structures or triangles — to convey the notion of cosmic dynamism and the trinity (e.g. Wayan Sika). This irruption of clear Hindu symbolism denoted the Hindu internationalisation of Bali and the concomitant awareness of the unavoidability of change, including the presence of history. The introduction of the notion of destruction came unavoidably along: one finds it in the works of artist Nyoman Erawan, whose painting deals with “decay” and Kali Yuga — a Hindu-defined era of conflict, the cycle we are said to be in present day.

Photo by Richard Horstman (lifeasartasia.com)

Yet, all these changes were inner “discourses”, held within the boundaries of the Balinese community. Never did they engage the outer world. This changed with the arrival of Made Wianta on the cultural-cum-artistic scene in the 1980s. Wianta did not wish to discuss Bali from a purely Balinese perspective. In most of his works, especially his installations, he “challenged” the impact of globalisation on Bali.

Made Wianta foresaw before everyone the implications of Bali’s insertion into the global world, and the problems likely to be faced as a consequence of this new interaction.

He started in the late 1980s, when he made a performance in which offerings were carried in a car. Not yet a reality at the time, it became so soon after. A few years later, he “performed” an automobile accident on a Balinese road. Mobility, he was telling us, was transforming the dream of a Balinese harmony. Wianta had also a dramatic understanding of the problems of violence. He had witnessed the bloodshed of 1965, where Western-imported ideology — Communism — had torn across a social hierarch that was already harmonious. He dreamed of harmony, not as “identity”, like most of his colleagues, but as a paradigmatic goal. In this context, he felt so much the violence inherent to the rapid transformation of the world that he decided to celebrate peace in a huge performance. He did so ahead of the new millennium, in 1998 as Eastern-Indonesia was wreaked by civil war,. He had organised 2000 students to spread a 2000m cloth all along the beach of Sanur.

The cloth, inscribed with peace messages, has both aesthetic and symbolic qualities. Upon it, Wianta drew abstract, archetypal and universal characters that blend with other world cultures. They represented natural forces such as waves, wind, movement which are themes directly connected with the performance. Movement is highly symbolic as it represents life and the events that unfold at every moment in Indonesia.

The 2000 high school students (dancers) and length of the cloth symbolised the year 2000 (millennium era) and our reflection of our peace. The students also have an aesthetic and symbolic dimension; they are the key performers and the most important symbols in the events. To Wianta peace has so many connections with teenage and student life, from their creativity to their experiences with conflict, narcotics, free sex and crime. This is very important for the next generation. Today, many of the students hold positions in various important jobs; Wianta believed in the importance in their partaking in voicing peace from Bali to the world.

Four years later, in 2003, after the Bali Bombing of October 2002, Wianta made an installation-performance which consisted of 25-30 “horror” paintings. They consisted of photographs of the bombing site and corpses repainted with blood taken from the Denpasar slaughterhouse.

The result was exhibited in a totally black-painted room one could only access with a small flashlight, in the middle of which was a simile island of Bali with corpses strewn on it . A “violent” statement against the violence of reality. It was exhibited at the 2003 Venice Biennale.

Wianta passed away two years ago. Among today’s artists, many still “talk” about Bali’s ever-dreamed harmony. Some refuse reality. One creates extraordinary colours to symbolically blend into the void (e.g. Wayan Karja). Others link Bali’s evolution to the historical path and pain of Indonesia (e.g. Mangu Putra and Kun Adnyana).

Who will answer the challenges raised at the international summits increasingly hosted in Bali? Will the island’s perpetual efforts to ‘retain’ harmony seep through the walls of the convention centres? In a world seemingly always under the threat of war, one can only hope. Or perhaps the works of Wianta should be put on display as a stark reminder.