Tumpek Kandang is a day dedicated to Sang Hyang Rare Angon, the god of all cattle and livestock. On this day, domesticated animals on the island will receive great attention; the cows are washed in the river and dressed up like human beings, with special cone-shaped spirals made of coconut leaf placed on their horns.

The pigs are decorated, with their bellies wrapped with a white or yellow cloth. Prayer is, of course, offered to the gods for the welfare of these animals. Holy water and rice are sprinkled on the heads of these animals at the end of the ceremony. Our cultural expert Jean Couteau explains in detail the intricacies of this unique holy day for the Balinese Hindu.

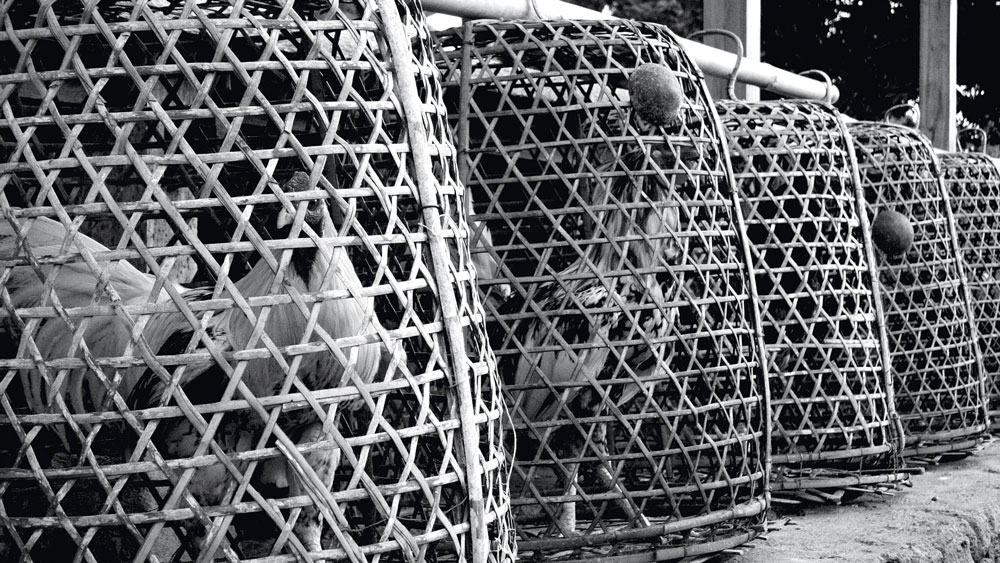

To see animals celebrated in a festival specially dedicated to them, you have to be in Bali. Some of you may have witnessed this festive day, Tumpek Kandang, addressed to pets, pigs, hens or, to be more precise, to the gods that symbolise them.

But before talking about the rites, a few words, boring but necessary, must first be said about the Balinese calendar system. There are two kinds of calendars in Bali: a 12-month lunar calendar and a 210-day ritual cycle called the Pawukon. The Pawukon year is divided into 30 weeks or wuku in the local language, each of which has its own name. The pawukon is itself divided into many shorter “week” cycles which run concurrently. Besides the 7-day “Babylonian” week, there are a 3-day week (Pasah, Beteng/ Tegeh, Kajeng), and a 5-day week (Umanis, Paing, Pon, Wage, Kliwon).

The conjunctions of the 5-day week and the 3-day week with the 7-day week determine most holy days. Thus each conjunction of the Saturday of the 7-day week with the Kliwon of the 5-day week will be a Tumpek, which will occur every thirty-five days and 6 times in a full 210–day Pawukon year. For each cycle of 210 days, there will be an otonan or, for temples, an odalan anniversary.

The 6 ‘Tumpeks’ of the cycle celebrate each important aspect of Balinese life:

Metal instruments on Tumpek Landep, a wayang puppet show on Tumpek Wayang etc. The Tumpek Kandang corresponds to the celebration of domestic animals.

Why these rites? Because if humans have in them three principles of life (Tripramana) consisting of bayu, sabda, idep, (life/energy, voice and thought), animals have two (life and voice), and must therefore be honoured as well. Plants do have their own Tumpek as well, Tumpek Uduh, because they have one principle (life/energy).

Usually, it is only women, or more precisely housewives, who are involved in the rites: they look after pets, hens and cattle and feel it as their obligation to look after the welfare of their animals. Yet, for big-scale tumpek kandang holy days, which occur every ten years or so, only a temple priest (mangku) or a shaman (Balian sesonteng), has the authority to “send up” the offerings to the gods, whereas when modest offerings are concerned, the woman of the house will conduct these rites.

The scale of the rites depends on the number of animals owned by the family. The more a family owns, the grander the ceremony. The most important ceremonies are found in the mountainous areas, whereas elsewhere a simple, ceremony with few “bebanten” offerings will suffice.

The opening to the ceremony is a set of offerings addressed, usually in the morning, to Rare Anggon, the godly herdsman – a manifestation of the God Siwa. But the rites and offerings dedicated to cows and pigs (Ngotonin sampi wiadi celeng) are performed in the evening. At four p.m. when the sun begins to glide down to its “royal bed” in the west, the offerings are ready. The pigs and the cows have been washed in the river and are therefore ready to be presented with their offerings, which vary according to the animals, whether they are cows, pigs or pets.

Once offerings have been presented to the deity, people may eat them. But this does not go without limitations. It is interesting to note that only women are allowed to eat the leftovers (surudan) of the offerings dedicated to pigs. According to Balinese belief, if the leftovers are eaten by boys (and men, in general), they will become lazy and stupid and even lose their prestige or authority. Yet, the leftovers (surudan) of the offerings dedicated to cows may be eaten by both men and women after they have been sacrificed to the aforementioned animals. I let our feminist readers elaborate on the gender bias such discrimination reveals!

There is of course a hierarchy of sorts between animals. Grilled/barbecued pork (suckling pig, or babi guling), is included in the offerings sacrificed by those who raise cows only. On the other hand, those who raise only pigs just dedicate modest offerings, whereas those who raise chickens, ducks and the like dedicate even smaller mewadah tamas offerings.

An interesting anecdote is that people may have pledged to make an offering to a female pig (bangkung) if this animal gives birth to many piglets. Once the vow has been uttered, the owner must fulfil his/her pledge. He/she will slaughter a piglet and dedicate it to the bangkung itself, together with otonan offerings such as those given for a full Pawukon year.

In preparing the offerings, the owner has to perform a strange ceremony:

To cut a little part of the toenail, the tip of its snout, the tip of its tail, the tip of its ears, and a little of its hair. Then the female pig is to be served with the hair and the toenail cut by its owner as the symbol that he or she has fulfilled the vow he/she once made.

As the owner dedicates the offerings to his/her pig, he/ she will say: “Buin pidan yang nyai ngelah pianak dasa, kuala apang luh dadua. Lakar tinggungin icang nyai kayang oton nyaine”, meaning: “If you can give birth to ten piglets among which are two female ones, I will dedicate offerings to you on the next Tumpek Kandang day, when you have your anniversary.

If the bangkung gives birth to exactly the number of piglets as the owner wishes, the owner will soon slaughter a female shoat (young pig), which is called kucit in the local language, grill/barbecue it and dedicate it together with the other offerings.