One of the best ways to learn about different cultures is by looking at how they deal with death; i.e. how they dispose of people’s corpses and what status and attention they give, if any, to the latter’s soul.

In Bali, death is dealt with in such a way so as not only to get rid of the body, but also to open to the soul the path of release. This soul will then become a fully-fledged ancestor dwelling in what is called the ‘old country’ (tanah ane wayah), somewhere above the island’s mountains.

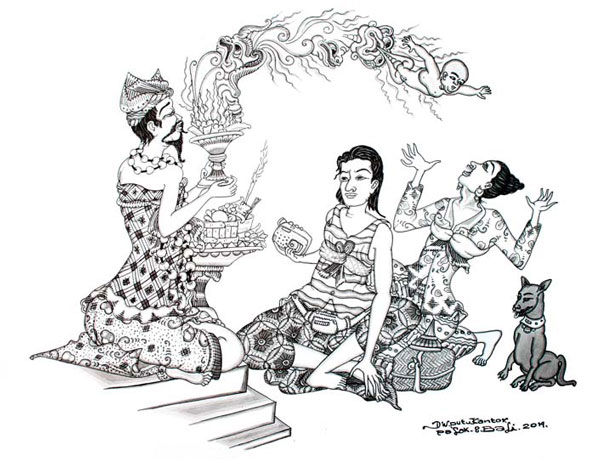

It is to obtain protection of ancestral souls that festivals are held, complete with welcoming gifts of food, dance and music – the magic of Balinese culture. In urgent instances, the ancestors are consulted through the intermediary of a balian (medium), whose function is to make the gods or spirits “talk” about what happens “over there” (kedituan), in the invisible world (niskala). Any disorder in this kedituan has an impact “over here,” in the world of humans.

The protective function of the ancestor (dewa hyang or raja dewata dewati) can be ensured only if the rituals of death are properly implemented, lest the soul of the dead turns into a lost soul (atma kesasar) and wrecks havoc among humans – something which happens, according to many, more often than they would like.

Hence, the importance of the bathing of the dead, the ngaben (cremation) and the various post-cremation rituals of release (mukur, majar-ajar, ngelinggihang), the purpose of which are to definitely separate the bodily components – thrown as ashes into the sea – from the spiritual components – the soul – which is sent back to its ancestral ‘old country’ (tanah ane wayah), while a shrine and effigy is prepared in the family temple to welcome it back with other ancestors during festivals.

To this Austronesian conception of the ancestor’s cult, the Balinese have added the Indian conception of reincarnation.

Thus, there is a cycle of lives and deaths, with the soul taking up a human mantle, which it must release during death on its way back home, above the mountain. In the Balinese traditional version of Hinduism, people always reincarnate among their kins.

However, this system of reincarnation creates a snag and it occurs whenever there is a pregnant woman’s death. According to the Balinese, once the red and white “desires” (Kama bang and Kama putih – egg and sperm), have successfully met and are united, it means that an ancestral soul is coming down to earth (incarnating).

Beginning with the magedong-gedongan ceremony, on the seventh month of pregnancy, the foetus is thought to be an incarnating being, which means that the woman is carrying two souls at once – her own soul and that of the foetus.

If she dies, the logic goes that the soul of the foetus should be dealt with in a way similar to that of the mother and, eventually, find its way back home to the ancestral home above the mountains. It should go back there even though it was not yet fully born.

The difficulty comes in separating the baby foetus from its mother. This is entrusted to time, with a little help from family members. So her corpse is not buried, nor cremated, directly, it is instead put to wait in an open pit for a period of time, usually not exceeding three days. Stones are put on her swollen womb to put pressure on the foetus inside.

Then, as in other types of death with burials, a bamboo separation is set all around the grave to isolate the spirits (negative forces).

These forces must be present, because they are usually deemed to be the real cause of the death, which is indeed confirmed by the consultation of a balian (medium), who “transmits” the request of the soul trapped in the women’s womb.

Then, the men of the banjar (village) association take turns to guard the grave. They spend their time talking or playing cards while waiting for what everyone expects: the “birth” of the dead child. After three days, indeed, the body starts decomposing, and sometimes, the dead baby comes out of “its own”; if it does not, in some villages, one pokes three times at it to push it out.

Even if it does not come out, the soul is eventually thought to have been released, and one can then carry on with the normal proceedings of death. Waiting for a cremation, sometimes years ahead, the mother is buried in her own part of the cemetery, in the place attributed to the persons of her clan, while the child, if it comes out, is buried in the setra bebajangan (children’s cemetery), located in the purest part of the burial grounds.

Upon its aborted “birth,” the soul of the dead baby is still pure and ready to “go directly back home,” i.e to the ancestors’ abode. It is deemed unbesmirched by the bad deeds of life and will therefore be able to reincarnate again very quickly, without having to pass through, and be purified by, neraka (hell/purgatory), like ordinary souls do. For this reason, when a cremation is organised, it is organised apart, with its own offerings and rites.

It must be said that the most ghastly aspects of this tradition above is fast disappearing.

Illustration By Dewa Putu Kantor