The Jakarta Post of November 3rd brought interesting news: “Residents of the Angke Rusanawa low-cost apartment complex in West Jakarta were shocked by the discovery of a man’s body in the ceiling of an apartment early on Monday.” Residents allege the man died of an electric shock while trying to peep in on a newly wedded couple!

Indonesian moralists will say that peeping is the result of “negative” influences from the West, but it is not. Peeping is actually one of the most ancient Indonesian, and especially Balinese social habits. The Rajapala story tells how a boy steals a girl’s dress while she is bathing so as to force her to marry him. “Hard core” peeping is still documented. The Arjuna Wiwaha, an Old-Javanese poem from the 11th century, relates how the gods bestow the hero Arjuna, having defeated the evil Niwatakawaca, with the beautiful nymph Supraba, only to be peeped at in the act by the ladies-in-waiting.

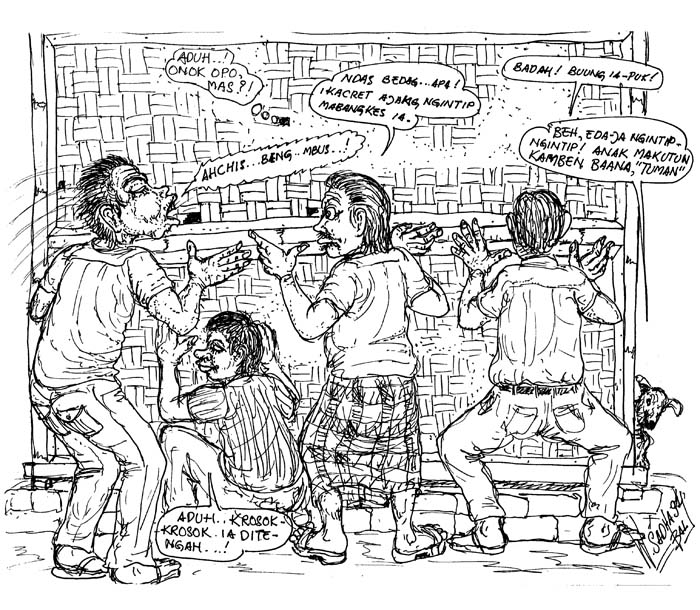

The Balinese puppet masters, for whom the poem is a sort of Bible, have not failed to note the educational function of the story and have made peeping a regular feature of their plays. Thus, peeping in Bali has a long history. It may have taken a new bend, due to the presence of tourism and modernity.

Peeping, from the point of view of its “victims”, is in Bali quite an experience indeed. When you are in love, you usually think that the world belongs to you and your lover alone. Privacy is the rule you adhere to. Actually, it is quite the contrary here in Bali! If you have the “love look” on your face, and you hang around Pandawa Beach with a radiant-looking partner, chances are, prospective peepers will notice you. Whether you are in a rented room, in a honeymoon bungalow or on a moon-lit sandy beach, they will show up sooner or later.

The peepers can manifest their presence in diverse ways according to the place where you are “performing”. Sometimes you will hear the croaking of frogs coming from your ceiling– very few peeping Toms are electrocuted.

_____

On other occasions, when you are lost in a deep French kiss on the beach, you might fail to notice that the leaves are moving in the opposite direction to the wind. These are signs that they are there, peeping at you, unabashedly enjoying themselves.

_____

If you have become aware of them, it is best to ignore them. Just carry on, as if nothing has happened. Just enjoy it, and they will soon get tired and leave. If you show that you suspect that they are peeping, they may all of a sudden, run away in a confused scramble, croaking and neighing loudly. This is more embarrassing, especially if it is your first night of love. It may cut the act short.

The fact that they have peeped at you does not embarrass your “peeping Toms” in the least bit. You may stumbled upon one of them in the streets and even if you don’t recognise him, he certainly will and will say, with a broad smile on the face,” Eh, Made, I watched you with pretty Asih last night. You were not bad at all. How many “rounds” did you end up with?”

If the conversation degenerates into this type of questioning, please be civilised. Don’t punch the fellow in the face, as an uncouth Westerner might. It is better to laugh away the matter with a comment such as: “I don’t remember, I am not very good at counting.”

If you know for sure that he was the only “peeping Tom”, you could try hitting him on the nose, but whenever you suspect someone you’d better not take any risks, as the Balinese seldom attend peeping sessions alone. As a collective-minded people, they like to take their friends to the “shows” and the chances are that there was an eye at each hole of your room or twenty youths crawling on the beach, or at least half of the village youth association of the banjar was present.

This means that, quite unwittingly, your prowess -or the lack of it- is made public to the whole village. Since they all joke about the peeping, and are all friendly, you too will feel like joking and being friendly with them. A bond is thus created, which protects the girl, all the more so if she belongs to the village.

This means that, quite unwittingly, your prowess -or the lack of it- is made public to the whole village. Since they all joke about the peeping, and are all friendly, you too will feel like joking and being friendly with them. A bond is thus created, which protects the girl, all the more so if she belongs to the village.

The function of peeping is therefore to remind lovers of their obligations. Sex is not only an act between two individuals; it is also a social responsibility.

Where does the peeping usually take place? Traditionally, in the public baths which are in the open but also behind the holes and curtains of Balinese houses. The village youths will never fail to notice a couple surreptitiously leaving an arja arja opera performance ahead of time. Tourist resorts are also favorite peeping spots, especially the beaches of Sanur, Legian, and, as of late, the Bukit, where peepers can peep in the daytime, with binoculars, from the top of a cliff.

Alas, things are fast changing with the arrival of mass tourism. Peeping loses its naive and educational flavor and becomes just an aspect of the business of sex. For prospective gigolos such as those found on the beach of Kuta or in the late night cafés of Ubud, it might be a distinct advantage to know all the sexual tricks of Western and Japanese women. Therefore they team up with hotel losmen owners or guards, who show them where the best peeping holes are, and how to conceal themselves. The hot spots are the honeymooners’ rooms. Although these days, guards are more selective and reluctant to share.

So, ladies, if you fall in love with a Balinese gigolo on your second trip to Bali, the guy might have learned your favorite “games” while you were honeymooning here ten years ago with your then legitimate husband. Your “gigolo” was there.

After all, training is the key word in the hotel industry, isn’t it?