Journalist Eric Buvelot and socio-ethnologist Jean Couteau have recorded 20 hours of discussion about changes that have happened in Bali since the 70’s. The conversation was structured and segmented according to many different aspects of Balinese life, mostly from a socio-historical perspective, to trace all the overturning in Balinese mores since 50 years, when modernity started to shape new behaviours down to the village level.

At the core of these changes is the birth of individuality in a communal society and the revolution it implies. The resulting changes have been more significant in 50 years than the ones happening during the previous millennium. At the end of this project, a 16 chapter discussion-based book will be published with the purpose of measuring to which extent Bali has morphed in so little time, a work never done before, encompassing all Balinese social and cultural matters. The French edition is due at the end of 2020 at Editions GOPE. The English one will follow next year. This month, we take a look with them at the status of women and how it evolved in modern times around concepts like love, marriage, divorce, polygamy, sexual liberation or even homosexuality.

Eric Buvelot [EB]: What can you say about love?

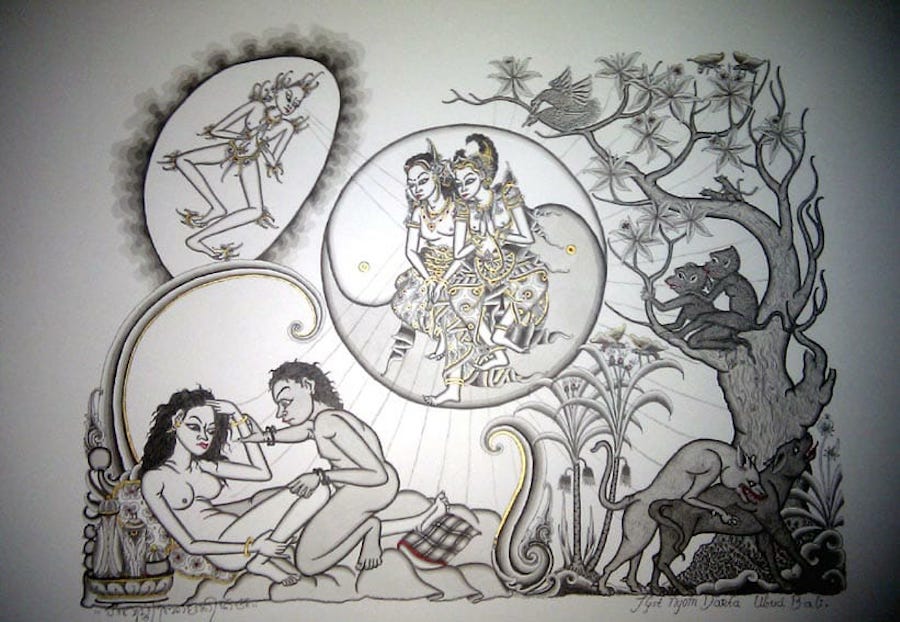

Jean Couteau [JC]: In deep Bali tradition, love reverberates cosmic relationships. Thus, in classical paintings, gods appear often alongside humans, in their own love scenes, for example Sang Hyang Ratih together with Sang Hyang Kamajaya. Dewi Ratih is the Moon Goddess, whereas Kamajaya is the god of Love (from Kama, sperm). There is a famous myth, according to which Kamajaya was punished and burned to death by the God Siwa. Ratih asked Siwa to follow her beloved and was thus reduced to ash herself. Ever since, love spreads as ash throughout the world.

It is divine power that activates human love. God is always present. As for sexual intercourse, it is said to be made possible through the intervention of Sang Hyang Deleng, “the god of the love stare”. This is roughly translated as the encounter of the two Kamas, white (sperm of man) and red (ovule of woman).

EB: It is love at first sight…

JC: Yes, it is forces from ‘out there’ that determine love. And it starts well before the current incarnation. Falling in love means jatuh karma: obeying to one’s karma, to obey the determination of previous incarnations. When incarnating, meaning being born, one comes right out from the tegal penangsaran, the Balinese “field of sorrow” or purgatory, and into this world.

Sometimes, one has to pay a “debt” of love, a debt incurred during the previous incarnation or even during one’s sojourn within the field of sorrow. For example if a female soul helped you cross the ‘shaking bridge’ (titi ugal-agil) and thus prevented you from falling into the flames of hell, you may well have a debt toward the corresponding female in real life.

EB: Is this really that far from the Western concept of love?

JC: It is totally different. The Western concept of love only appeared with modernity, in particular through the movies, starting in the 1950s, via open-air cinema screenings.

EB: What about the sexual aspect?

JC: The choice is a male affair. Women have little rights. The key word here is “to grab”, ngambil in the high-Balinese version, ngejuk in low-Balinese. It is often impossible for women to refuse the sexual request. This may have changed among educated Balinese, but marriage through rape (melegandang), even though banned, is still probably occurring in some parts of the island.

EB: So all of this has changed in the last 50 years? Then, where did young people meet?

JC: During drama gong, wayang or topeng drama performances. Balinese society was still predominantly rural, apart from a small educated elite. There were only 150,000 inhabitants in Denpasar, compared to a million today. There was not partying in Kuta, where only a few hundred hippies lived. Boys and girls met during the night shows accompanying ceremonies. Most often around an improvised stage (kalangan) lit by an acetylene lamp. The setting was, typically: on the first row, the children, seated cross-legged; behind them the girls, standing; and behind the girls, the youths, pushed around by the impatient crowd. This is, show within the show, where whispers of love and promises were exchanged as well as subtle caressing of backsides.

EB: Yes, but this still exists!

JC: Village festivals are not as popular as they used to be. Now, the budding Don Juans go to the city, or to Kuta. They prefer modern music to gamelan.

EB: Is polygamy legal in Bali?

JC: In modern discourse, polygamy is frowned upon, but in the reality of ordinary people’s life, it is perfectly acceptable… Let’s recall here that, in pre-colonial times, the king of Ubud, had something like 130 women. The women palace attendants, the penyeroan, were considered to be sexually available. Today, according to the law, it is not allowed, unless the first wife gives her consent.

Divorce is not really a way out for women. It is complicated by the fact that, when a woman marries a man, she also marries his clan, meaning his ancestors. She changes her ancestral affiliation. She thus passes from the ancestral gods of her father to those of her husband. For her, the divorce proceedings entails two ceremonies: one that follows the divorce proper, and one through which she is allowed to worship again in her father’s shrines. This is emotionally very demanding, so many women prefer staying with their unfaithful husband, which implicitly authorises the latter to take a new wife. It is considered unwelcome, but a smart guy can easily set up a small wedding ceremony in honour of the lower forces, which is called byakala. And the trick is done. The fellow can have one or two more or less camouflaged families. And the children are not born without a father, which is what matters, more than the law.

EB: However, does it happen today that it is the woman who requests a divorce?

JC: Yes! Despite what I just said, it is undeniable that women now have more autonomy. This is linked to education and urbanisation. Yet, in traditional circles, it is the woman whose husband is cheating who is considered in the wrong. A village friend may well come up with nice words: “If you cannot meet your husband’s needs, don’t be surprised if he goes looking elsewhere for his fare.” I must add that many modern educated Balinese will deny all these unsavoury aspects of the women’s condition. They refuse sociological reality. But when one starts to talk with the women here, they will tell what is really happening.

EB: What does the Balinese man see in the Western woman?

JC: An instrument of political and economic emancipation. To sleep with a Western woman is to deny the historical domination over the native woman by the white man. Sex creates a kind of equality. By the way more and more real. During the colonial period, white women only slept with princes; then there were the artists; now even taxi drivers are doing the trick.

EB: Well, one question: female homosexuality in Bali… Does it exist?

J C: It depends on the meaning given to the words. The practices of mecenceng juwuk, the women caressing one-another sexually, was long considered normal, and not as any deviation.

EB: Is sexual liberation happening in Bali?

JC: There is not enough autonomy of the person to enable this to happen on a large scale, at least in the Western sense of sexual liberation. There is rather behavioural differentiation. In the urbanised South, one witnesses the presence of contradictory social norms, which compete on the ground, according to one’s surroundings: Western standards, Islamic standards, modern-urban standards etc. School and, more and more, social media are playing an increasingly important role in this field.

Yet, in most villages, things remain very traditional. What matters is to avoid impurity. If you elope a woman by force, you have to cleanse your deed by a ceremony: it is necessary to restore equilibrium. And a divorced couple should do a ceremony before having sex again.

EB: Is there an upheaval of values?

JC: Yes, it started concretely with what we said earlier: the relationship with space changes with mobility. Born villagers, many Balinese become urban… And there, everything changes, the sexual and intellectual behaviours. Little by little. Traditionally, Balinese sought women in their village or clan. Except for those who benefited from a wider geopolitical environment, essentially the aristocrats, who could find a woman in another puri in order to consolidate their alliance network.

EB: What is the main impediment to women’s emancipation?

JC: The confusion between philosophical norm and social reality. When some intellectuals tell you that since there is symbolic complementariness between Purusa/Male/Spirit and Pradana/Female/Matter, there is also equality between men and women. They confuse philosophical norm and social reality and thus cover a reactionary practice with a progressive affirmation. Despite all the demands for change, the purusa always come first.