On an island that can now feel overrun with hotels and resorts, few can rival the history of Tandjung Sari hotel in Sanur. One of the first resorts in Sanur, Tandjung Sari was at the forefront of the influx of tourists to the island and has remained one of the ‘seminal boutique hotels of tropical Asia’ over the last 60 years. Along the way a legacy has been handed down from its founders, to their children and now to a third generation. Over the next three editions, we’ll trace the history of this creative family and the impact they’ve had on their island home of Bali.

Text by Diana Darling, Edited by Summa Durie

This is Part 1 of a 3-part series.

Go To Part 2 – Go To Part 3

Tandjung Sari is an ageless beauty. At now sixty years old, this small hotel on Sanur beach, shaded by huge trees and quietly sheltering treasure at every turn, remains serene, discreet and elegantly modest.

It began in 1962 as a place to spend the night for its owner Wija Wawo-Runtu (1926–2001) and his English wife Judith when they came to Bali from Jakarta on shopping trips for their antiques business. Soon extra bungalows were built to accommodate friends, then friends of friends. It became a hotel almost without anyone noticing it; but within a few years it was internationally renowned among smart people as the place to stay, if you could get in.

What drew people was the Tandjung Sari’s judicious blend of the low-key and the luxurious. The architecture was simple, using local materials and Balinese building techniques; yet the location was on prime beachfront with wonderful gardens; the rooms were furnished with Balinese antiques; and the hospitality was warm and sophisticated. Guests had the feeling of experiencing a highly refined version of “the real Bali” with all its sounds and silences, its deep perfumes, its bare-handedness and hilarity, and powerful enchantment at the edge of a spangled sea — while still being able to luxuriate in a good bed or over a gin and tonic.

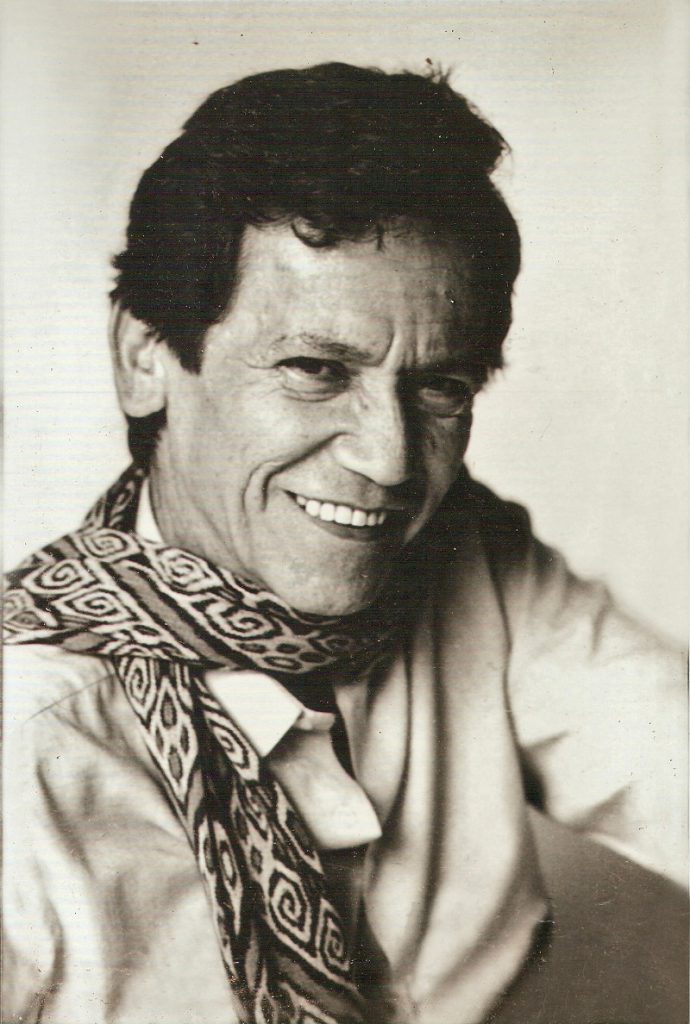

All this was orchestrated by the very central figure of Wija Wawo-Runtu, a multi-talented man with more than his fair share of beauty and a ceaseless, good-natured charm. Rather informally and with much flair, he was a filmmaker, interior designer, collector and dealer of art and antiques, amateur architect and scholar of Balinese culture. He was a reader, a scotch-drinker, an entrepreneur, and a devoted father.

If you conjure Sanur in the early 1960s when the Tandjung Sari was born, the vision you get will be a quiet one. The beach then was nearly deserted during the day, except for the coming and going of fishermen in their bright little boats, and at low tide the harvesting of coral from the lagoon’s protective reef. The Balinese considered coral a handy building material for walls, and as they burned it on low fires to make slaked lime for mortar, the smoke spread a pungent gloom smelling of the sea. At night it was very dark unless there was moonlight. The Balinese didn’t live on the beach. The sea was understood to be a place of magical danger, and for this reason they built a string of small temples along the coast. They planted coconut trees at the edge of the beach and tethered their cows in the shade to graze on the rough grass. The ancient settlement of Sanur village was inland. The few lights here and there along the beach would be the tiny flames of little kerosene lamps; electricity was still scarce in Bali in the 1960s. Evening was a time to gather close to home. The night sounds would be crickets, frogs, owls, the sea and the wind.

Wija Wawo-Runtu understood that what visitors wanted was intimacy with Bali. They wanted to feel the air of Bali on their skin. They wanted to inhale the scent of its incense and flowers — to live in what they imagined was a Balinese way, but more comfortably.

Wija was born in Utrecht, Holland in 1926; his mother was Dutch, and his father was from Manado, North Sulawesi in eastern Indonesia. The family moved to Sukabumi, West Java, when Wija was a child, and he grew up there. Wija married Judith, a young English painter, in London in 1952, and their first child, Fiona, was born there. (Their five children — Fiona, Iskandar, Timi, Yaya, and Ade — were born within the first six years.) In 1953 the couple decided to move to Jakarta, Indonesia. They designed and produced bamboo furniture. It was for the collecting of antiques and art objects that they often went to Bali, where they would buy old statues and other Balinese exotica with which people still love to decorate their homes.

Legend has it that Judith chose the piece of land on which the Tandjung Sari would be built while scouting the coast with Jimmy Pandy in a jukung, one of those tiny and gaily painted outrigger sailboats used by fishermen to skim the lagoon and venture beyond the reef into the seas of the Bay of Badung. One can imagine the pair sailing along the palm-fringed beach in the bright wind and seeing an exceptionally pretty stretch jutting a bit further into the lagoon than the rest. After some inquiries, it was found that the owners were willing to sell the land. There was nothing on it but some large trees and a coconut grove, with a small temple by the beach, called Pura Tandjung Sari — ‘temple of the cape of flowers’. They built a little house of woven bamboo with a roof of woven coconut leaves. Fiona Wawo-Runtu says of her parents, “Maybe their courage came from being artistic. Artists always say, ‘Let’s try this, and if it works, ok, and if it doesn’t work, it doesn’t matter’.” Around the house they planted a garden that was a profusion of flowers. Their little paradise attracted friends from Jakarta, and by 1962 they had built four small bungalows for friends who wished to visit.

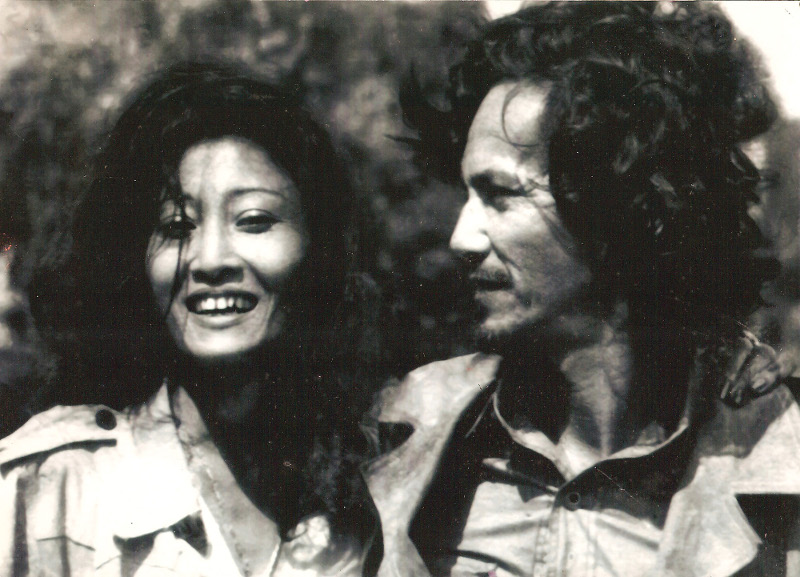

In August 1964, Wija remarried. Oemiati Soesetio — known to everyone as Tatie — brought to the marriage her four young children: Agus, Cha-cha, Buyung and Riri. Tatie and Wija had met the previous year, “three days after the eruption of Gunung Agung,” she recalls.

The transition seems to have been a remarkably harmonious one. Tatie’s children were fully absorbed into the family, and divided their time between the Tandjung Sari and Kediri, East Java, where Tatie’s parents lived; and all four children took the Wawo-Runtu name. In 1967 Wita was born to Wija and Tatie, her name a conjunction of her parents. Judith also remarried and yet maintained her links with Bali. Judith and Tatie remained good friends until the end of Judith’s life in 2007.

During the early days of Tandjung Sari, Wija and Tatie ran the hotel almost like a private home. Tatie recalls that “Wija mixed the drinks, I was in the kitchen, and when I was through in the kitchen we entertained the guests.”

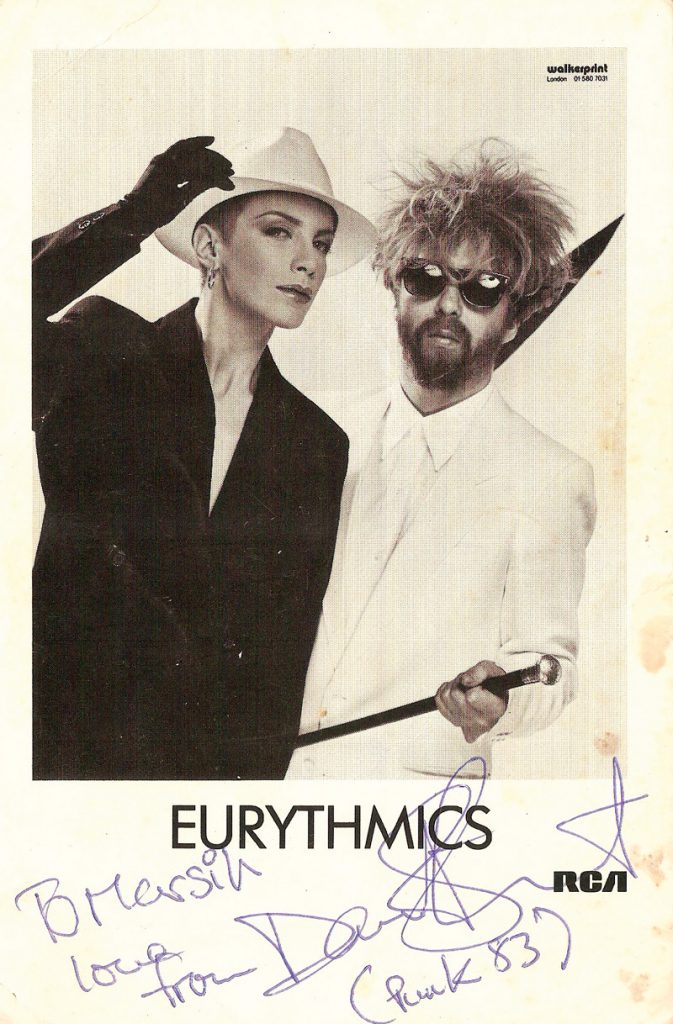

Inimitable and yet much imitated, the Tandjung Sari was famous almost from birth. From the very start in the early 1960s, it was known among the elite in Jakarta for the charm of its architecture and gardens graced with antiques, for its excellent food, for its special dance performances, but above all for its easy, gracious hospitality, which attracted interesting people who attracted others like them and created a self-perpetuating allure. Over the years Tandjung Sari generated a legendary following, welcoming guests like Ingrid Bergman, the Queen of Denmark, Mick and Bianca Jagger, Ringo Starr, Yoko Ono, David Bowie, and Annie Lennox and David Stuart. Wija’s “living room on the beach” became known near and far, and an endless stream of artists used the Tandjung Sari as a meeting place.

In April 2001, Wija’s brightly-coloured life came to an end in Todi, Italy. He was buried in Trawas, outside Surabaya in East Java. As family-friend James Roscoe reflected, “Was Wija first and foremost a bon viveur or a thinker, an architect or a dreamer, a father or a friend? How can one differentiate? To all of us, he was each and everything. Bali, Tandjung Sari and Batu Jimbar, are at the heart of much that he created, much that he loved: quintessentially personal interpretations of the island’s heritage, and also new ways to present it to outsiders”.

Tatie and the Wawo-Runtu’s children continued Wija’s vision for Tandjung Sari, a vision they hold true to until this day. In the next edition we’ll introduce the next generation of Wawo-Runtus and look at how they’ve continued the family legacy for creativity and innovation.

This is Part 1 of a 3-part series.

Go To Part 2 – Go To Part 3