Gatot was really fed up with his job as’ a Kernet (conductor) of a run down Oplet (collective taxi) between the terminals (stations) of Banyuwangi and Pesanggaran, in East Java. Although he could sometimes, on good days, make as much as 40,000 rupiah (about 25.50 US$), he had also noticed that there were ever more Oplet. His earnings, thus, were decreasing. Sometimes, it would get really bad, to the point where he would haggle and even fight with other conductors for a single passenger. And there was his wife waiting at home with their two kids. He needed money for them. It was then that he heard of Bali from someone he met on the road. “There was gold to be made in Bali”, the man told him.

On, on a bright day, two years ago, Gatot, 22 took his old guitar and crossed the strait to Bali. He went directly to Nusa Dua. “Go to Nusa Dua” his friend had insisted, “there is plenty of money to be made there.” Gatot’s only capital was his guitar, so he took the job of pengamen, or itinerant guitarist, going around from coffee-stall to coffee-stall (warung) and singing for the customers in exchange of whatever amount of money they would give. Often, they would give nothing or just a few coins: our friend had overlooked that the job of itinerant singer was alien to Bali. Only the Balinese who had lived for some time in Java would willingly pay him for his “shows”, and there were too few of them. Meanwhile, his stomach was growling, and the kids were waiting, back there in Banyuwangi. Dead-end? No! News travel fast in circles such as Gatot’s, and he had soon heard that there were many Javanese by the beach of Kedonganan.

So he went there, and there was good money: this was the fish season, and the fishermen, mostly from Muncar (East Java), were eager to have songs from their home. Here, he would get ten thousand rupiah and next door twenty thousands. After a few months, though, it soon became obvious to Gatot that he could not make a living with only his guitar and bad voice. The fishermen got fed up of his ‘shows’.

So he gave up singing and instead took up coolie work: carrying fish from the landing perahus (outrigger) to a waiting truck and from there on to the market of Denpasar, where he would take it to the fish stalls of the buyers of the Kumbasari market. This was a good job. Gatot could make more than one hundred thousand rupiah a day. He had his shack by the beach and the future seemed bright. But Gatot’s good luck could not last: The fishing season doesn’t last forever. After it is over, there is no work anymore. No work for Gatot.

Luckily, in those days, there was something else in Kedonganan: temptation. The shacks behind the beach were selling not only fish, but also ‘chicks’: girls. With ‘love’ on the cheap for the poor. 50,000 rupiah a pass. A real ‘social’ hub. When out of work, Gatot would often hang out there. He was lonely and there was beer, after all. He could drink up to 5 or even 7 seven bottles a night. Too bad for his pocket, and for his wife and kids too. Gatot did not have the soul of a pimp, which would have solved his financial problems. As a result he was soon not only broke, but in debt.

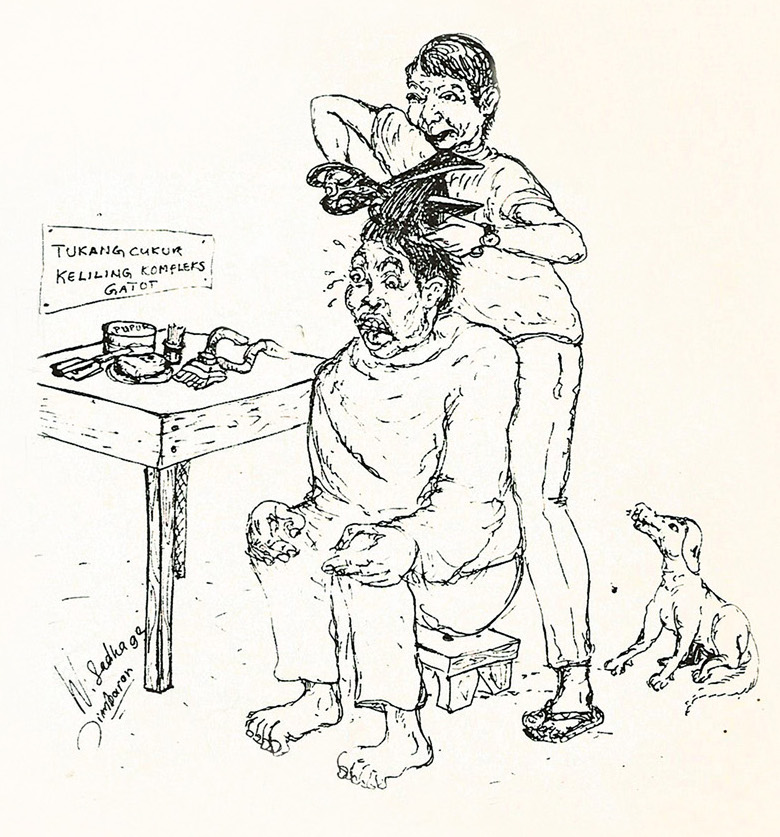

Drunkenness brings imagination. And one day, while Gatot was lying in a daze on his poor wooden bunk, he got an idea: he would buy scissors, a mirror, and a couple of combs and set himself up as a hairdresser. He would be the brothel’s hairdresser. And it worked. A local pimp lent him a hut just next to his food and drink stall.

The girls were somewhere in the back-shacks. It was a good business idea. The customers could have their hair cut while waiting for the girls. Or go to the girls while waiting for the hairdresser. The pimp was so pleased with the arrangement that he went as far as feeding him for free. Gatot’s earnings also increased significantly. Well-cut men see themselves as wealthy Don Juans, and contented men are always generous. This meant tips a plenty for Gatot.

At 20.000 thousand rupiah for a cut, Gatot, on good nights, could make up to 200 thousand. He was so busy he had no time to drink anymore. Once a month, he would send more than enough money to the village of Jajag, Banyuwangi. He had security. At last.

There has been a hitch, though. The last time I met Gatot was more than two months ago. The police have since closed the girls’ complex.

So I wonder where you are, now, friend Gatot? Are you back with your guitar on the roads of Bali? Are you in some other brothel, the trustful companion of a pimp and his girls? I don’t know. To me, only one thing is sure of you: you are a voiceless poor, on the fringe of the law!

Jean Couteau and Wayan Sadha