Who are the priests in Bali? Most of you have probably seen pictures of high priests, the pedandas, or even seen them on the roads or in temples. They are easily recognisable because they tie their long hair into a knot on top of their heads or wear a tiara while reading mantras. Pedandas are part of the Indianised elements of Balinese Hinduism which came to the island via Indian traders in the first century C.E.

However, arguably more important in the daily life of the Balinese are the temple priests, the mangkus. Why are the mangkus so important? Because they are the ones who invite the deities, the bataras, and their companions to come down from their mountain realms during religious events, particularly temple festivals. The mangkus’ function as the deities’ janbangul (meaning “ladder”) their way down to the Middle World, that place in Balinese cosmology where humans live between the underworld inhabited by the demons and heaven, the abode of the gods. The mangkus belong to the indigenous, ancestors’ cult side of Balinese religious tradition. They address the gods in Balinese, not in Old-Javanese, or in the archipelago Sanskrit used in the pedandas’ mantras.

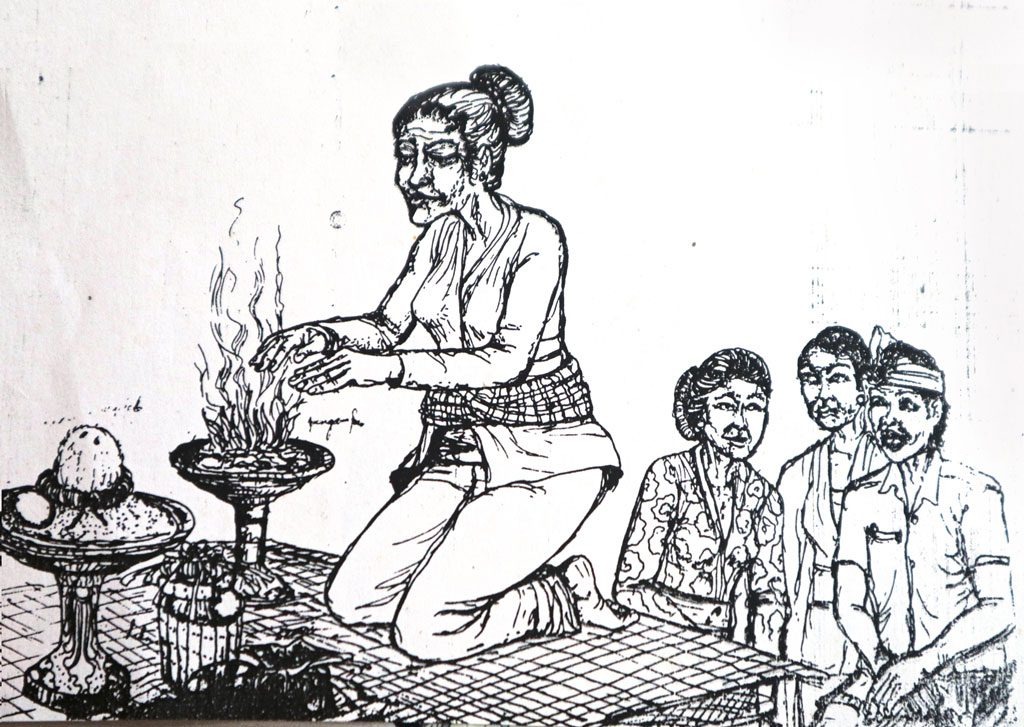

Illustration by Sadha Pdanda Istri

Illustration by Sadha Pdanda Istri

One does not become a mangku by chance alone. First, the position of mangku is vacant only on the death of the previous mangku. Then, one does not simply choose to become the new mangku. One is chosen. By whom? By various ancestors and gods attached to the temple. And how is their choice made known to the new mangku and the temple community? Through the services of a medium who is “wired” to the world “out there”, and who is recognisable by the weirdness (melik) he or she displays in life. Once identified, usually in a neighbouring village, this weird person (called jerodasaran or jerotapakan) is invited by the temple community to be placed under a trance (kerauhan, meaning to be “visited” in Balinese) so that he or she can nominate the new priest from among the attending congregation members. The medium sometimes slips into trance while seated; other times he or she dances around with hands full of offerings. This all takes place in a communal atmosphere laden with sacredness, accompanied by offerings and sometimes by musical entreaties:

First the weird one calls: “Oh you, gods from Mount Agung, from Mount Batur, from Mount Batukarau, from Mount Lempuyang, from all the important mountains, please come down among your “dew” (damuh – the people are said to be the “dew” of the gods) and tell us what we must do”.

At this point, it is no longer the medium who speaks, instead it is the visiting gods speaking through the medium and converses with the surrounding congregation:

“My dew, what is it I can do for you?”, says the god.

An elder member of the congregation will then reply in high Balinese:

“We want you, Oh Batara (god), to find us a way. We, ‘mere dew of you’, Oh Batara, want you to tell us whom you choose, because our previous mangku has passed away. Which one of us are you going to choose?”

To which the god replies through the medium in trance: “So, that is what you need! Someone to serve and accompany me? Very well”. Then the god, through the medium, picks up one of the signs or symbols provided that correlates to possible candidates. Rather than pick an unknown, the new mangkuis usually related to the previous, recently-deceased priest.

The medium then provides advice to the newly chosen priest: “My son, don’t you live anymore in dirt, because from now on you will become the ladder for me and other gods to visit the middle world. If you are impure, it is not only you who are going to be impure, but I too”.

The chosen person is usually transfixed, often in a near-trance. It is impossible for him or her to refuse what from now on becomes a duty. The gods have spoken.

If all goes well, the next step will be for the new temple priest to contact a pedanda priest and undergo a full anointment ceremony (mawinten), after which the new mangku will be able to “accompany” the gods (ngiring Ida Batara) whenever they come down on visits. The mangkuand the community will present the offerings, the dances and the gamelan music that have given Bali its reputation for beautiful ceremonies. People say that once selected by the gods, the mangku priest will learn the necessary mantras almost without any effort.

Yet, it is only after selection that the chosen person will realise the burden he or she now has to bear. The new mangku must not only accompany (ngiring) the gods during all the ceremonies related to the temple and its congregation but must also organise the ceremonies, prepare holy water, and attend to all the other details required for honouring the gods and assisting the community in their spiritual activities.

If the new mangku is a peasant living in the vicinity of the temple, life can easily be adapted to the myriad new duties. In fact, there are sometimes real advantages in being a mangku priest, not the least of which is gaining control over a piece of land linked to the priestly function.

But it is a different story when it comes to people who are modern, educated, and live and work in the city. Some can make do with their new responsibilities if the temple is a small family one. But if the temple is a big one? Some take days off to look after their temple. Others actually resign their jobs and go back to live in their village. Yet, there is another possibility: a newly-selected mangku who effectively postpones his/her anointment and goes on with life as if nothing had happened – and hoping that nothing does. Meanwhile the temple is provisionally looked after by a not fully anointed helper, and important ceremonies handled by other mangkus.

It is only when something serious happens to the community or to you that reality comes back with a vengeance for the neglectful party. Let us say that, as a child, you have been selected to be mangku priest and that the ladder for the gods relied on you. But then you have forfeited their sacred request to accompany the gods during temple ceremonies. You continue managing the catering business you have set up in Denpasar. You are a good Hindu, so you go regularly back to your village to attend cremations, temple festivals and other ceremonies. Whenever co-villagers ask you why you don’t fulfil your duty and accompany the gods, you just shrug. “Later,” you say.

Then the unexpected happens. One day, as your son rides his motorbike on his way to university, he has an accident. Or your wife is diagnosed with breast cancer. What do you do then? You go to the doctor. It doesn’t quiet you down, so you go to a balian (a medium) to ask him/her to check with the world “out there” to find out what might have gone wrong in your life or in the life of your village. It is only when the gods’ voice comes rumbling down in anger that you finally understand: you have neglected their request. And now they are making you pay for it.

Only then do you realise there is only one thing to do: go back to your village, cleanse yourself, and properly accompany the gods whenever they need you. Finally, you have become a real mangku.

If you don’t do so, at the next serious mishap, you may just become mad. Because not only you, but all the villagers will think you have been hit by the god’s ire. Your troubles will now be not only with the ancestors “out there”, but with the real people, right here.

And they say, in France and Australia, that religion has no impact on psychology!