“The superiority of purgatory over hell or paradise is that is has a future” – Chateaubriand

In these days of religious radicalism, the word paradise most often evokes the 40 virgins attributed to each martyr fallen in the holy war against crusaders, Zionists and other heretics and blasphemers. But considering the news from Syria and other places, is there really such a large pool of available girls in wait, eager to keep company with the blessed ones? I am not so sure.

- This and other stories can be found in Jean Couteau’s book, Myth, Magic and Mystery in Bali

In Bali, luckily, there is peace, and anyway, those lucky enough to gain access to paradise while waiting for reincarnation are not welcomed there by virgin girls, but instead by heavenly –and experienced—nymphs (bidadari). In either case, the “beneficiaries” are always men, of course. Am I suggesting here that you choose your religion according to virginity phantasms or to the experience of the welcoming party. Far from it. I am simply underlining how big the difference is between Abrahamic religions based on revelation on the one side – Judaism, Christianity, and Islam–, and the Eastern religions based on cosmic dynamism on the other. In Abrahamic traditions, the fate of the human soul depends on the way the person has fulfilled the requirements set in the corresponding revelation: belief in God, life free of major sins, and fulfillment of well-defined rites. Those who pass the test go to heaven, those who fail, go to hell, in both cases, forever. It is no joke.

In Bali, however it is not so much the belief in God which matters as the quality, good or bad, of one’s deeds (karma). God is Cosmos itself (Bhwana Agung). To emphasize its supposed Oneness is not relevant: it is both One and Plural. The notion of the person is also different. Each human being is a microcosm (bhwana alit) that should live in accordance with cosmic order. Each action has consequences (karmapala) during and after life at both the micro-cosmic and macro-cosmic levels. Only when the concordance of a human’s deeds with cosmic order is perfect can the corresponding soul blend (moksa) into the Sublime Soul of the world, the Paramatma. Most fail to achieve moksa, though, and thus reincarnate over and over again, each time coming back to earth “asking for rice”, as people say, after a period of cleansing –torture– in the “Old Country” of the dead souls. This is when one can talk of hell, which is actually but a purgatory.

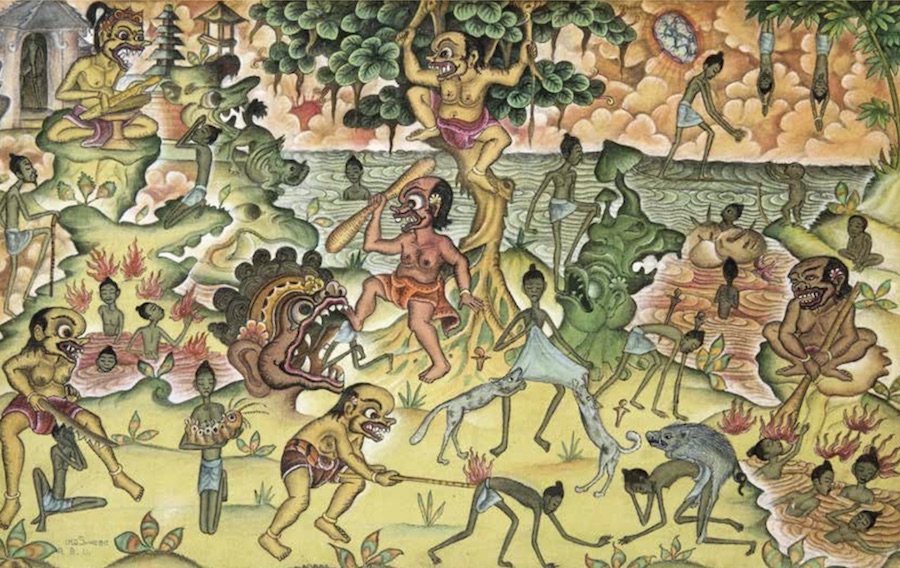

Hell is scary, but since one comes out of it –for some true baddies after tens of thousands of kalpa cosmic cycles—an interesting narrative has been created around what happens to souls during this darkest of pits. This narrative is illustrated in many Balinese artworks, the most famous of which being the ceilings of the Kerta Ghosa “Palace of Justice” in the Eastern city of Klungkung, the former capital of the island. The sojourn of the souls in hell is compared to a trek into a closed land run by Batara Yama, the lord of hell, with the support of his minions (Cakrabala) and other assistants. Tortures are found at all moments of this trek.

Let us depict what happens. After sojourning for some time around the corpse of the dead, there comes a moment when the soul has to face reality: it presents itself at the door of hell, guarded by an ageless man with a goatee, Sang Suratma, holding lontar manuscripts in his hands, on which are written the good deeds and sins of all the souls hustling to be interviewed and gain entrance into hell – and, who knows, into paradise (sorga). Suratma is a very harsh prosecutor. When questioned by him, the souls had better tell the truth, because he will know of every lie they may utter, and will punish them accordingly. His sentences are always harsh, especially for those of you – usually women of course – who could not fulfil their household duties. If for example, you could not weave, once you enter hell, you will be condemned to wear a sarong made from goat leather. Henceforth, you will have all the dogs of hell on your heels, biting and barking. And when you reincarnate later, you’d better behave – and learn how to weave. If you remained celibate, and thus did not have sex, don’t think you are safe. You have not fulfilled your duty: opening an incarnation path to a waiting soul. So you will probably be condemned to breastfeed a huge and ugly worm for I don’t know many years – only Sang Suratma knows. Once you are out, there is a good chance you will want to have many children.

After having passed Sang Suratma and being sentenced, don’t think you are safe. All your bad actions will be the cause of some tortures, especially if you have not reported the whole truth to Sang Suratma. And you cannot escape what is in wait for you. On this journey in this “land of Yama”, you have to pass under a tree with very dangerous leaves, the dagger tree (punyan curiga). Once there, you have to meditate. But it won’t save you. If you were a born liar, there are good chances that a dagger will fall on your upper lip; when you incarnate, you will be reborn with a harelip. Terrible. If you liked to peep on your neighbour’s wife, the dagger won’t miss your eyes, and, later on, you will certainly be born with damaged vision. If you were a thief and ran away after your deeds, the dagger may well fall on your legs, and you will be limp.

Of course, the worst tortures are for women. On the journey, all souls have to cross a very dangerous bamboo bridge, the “shaking bridge” (titih ugal agil). This is when women who have had abortions are exposed: the bridge shakes so much that they cannot keep their balance and fall into the pit, to be ripped into pieces below by waiting spears. Some may seem to be lucky, as they find the helping hand of a male soul, which helps them to cross the bridge. But their fate may be still worse, as they will find the guy back on earth, and will have to marry him, even though they don’t really like him. It will end up in divorce. The tortures addressed to men and women do not compare: unfaithful women have their vagina pounded by a burning stick, whereas Don Juans only have to carry around a load of coconuts with a big hole in each. No big affair. And if two sisters make love to the same man, they will be harnessed to the plough.

After undergoing these specified tortures comes the worst of all: when your soul is thrown into the big boiling cow-headed cauldron of hell, the Candra Gohmuka, guarded by Jogor Manik, whose huge ladle will plunge you back into the inferno each time you pop your head out to get out. There your soul will stay for years and eras, according to your sins. A piece of advice: once there, avoid any contact with the genuine baddies: Rawana from the Ramayana and Duryodana from the Mahabharata. And don’t make friends… even with foreigners, such as Hitler and Stalin. They are the worst. You may be punished with a few more years in hell.

There remains a big question: why are women subjected to more torture than men. An old friend of mine told me an interesting answer: women are part of the pradana, the “material” side of life. Therefore they are more subjected to more sins than men, who are the purusa, the “spiritual” side of life. No surprise then that, once they enter paradise, after all these tortures, female souls are not welcomed by male angels. Nymphs are for men only.

I wonder which punishment I will get from Sang Suratma for revealing such secrets of hell!!! Perhaps none, because the Balinese themselves like to joke about such topics.

This and other stories can be found in Jean Couteau’s book, Myth, Magic and Mystery in Bali .