Myths, folklore and stories in general are powerful forces. They are vessels in which morals and life lessons can be shared to societies, thus guiding them in the ‘right’ way of being.

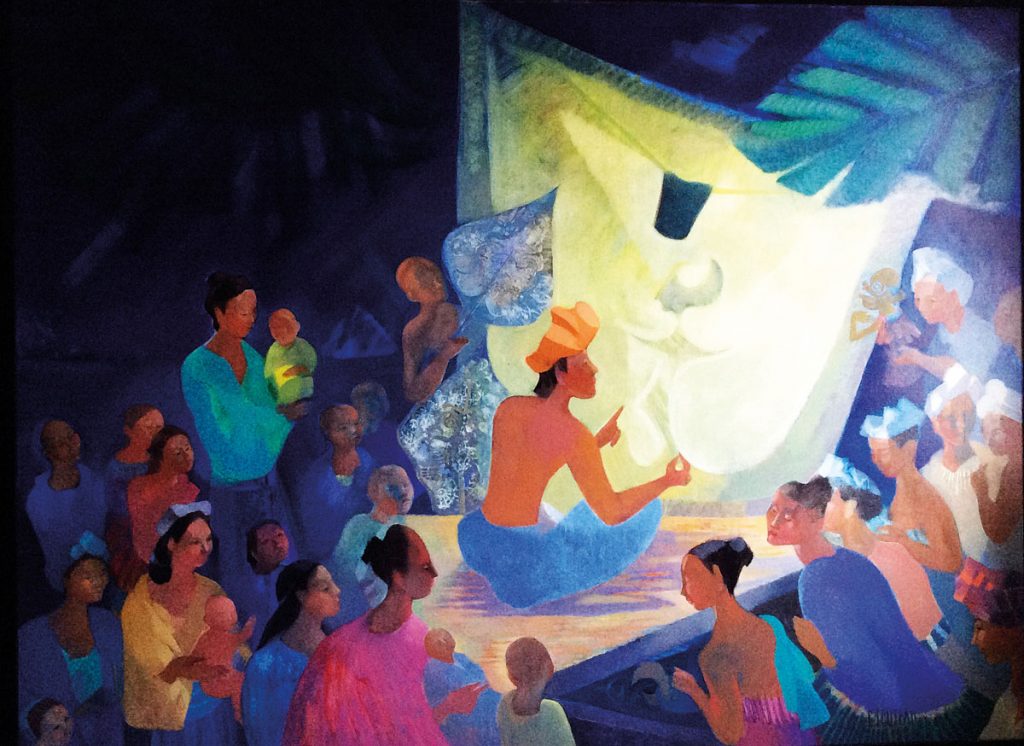

Myths are an important part of Balinese culture, mainly through the medium of the shadow puppet performance or ‘wayang kulit’. It is the puppet master, the dalang, who is therefore responsible for sharing the many Balinese myths and legends, thus spreading the morals society needs to remember.

Listen to Episode 15:

Available on your preferred Podcast Platform:

iTunes • Spotify • Google Podcasts • Pocket Casts • Radio Public

Episode Transcript

I was actually inspired to discuss this subject having watched an old documentary series called The Power of Myth. This was a 6-part PBS documentary which originally aired back in 1988. It’s presented by Bill Moyers and centres on his discussions with Joseph Campbell.

Many of you may recognise the name. Joseph Campbell is the author of The Hero with a Thousand Faces, in which he introduced the archetypal storyline of a protagonist known as The Hero’s Journey. This ‘journey’ is know often used in modern storylines to structure the rise, fall and redemption of the main protagonist.

How did he Campbell come to this? Well, he studied myths and legends from across different cultures and noticed that within their stories lay a common thread, a central theme that transcended geography. The stories and their content may have been different, but the overall exploration of this hero’s journey was similar.

Why is this interesting? Well, his findings tell us that, regardless of time and space, the stories that cultures tell are human nature. The collective stories that are told thus define the beliefs and desires of the entire human race.

His studies are under the sub-discipline of comparative mythology, which shows how distant cultures share the same core ideas through stories. He has been criticised by other scholars, saying that this destroys the local flare of each story — but for me, instead it creates a global community, an understanding that we are one and the same around the world. Driven by the same wants and needs – and for that same desire for fulfilment in one’s life.

Psychoanalysts of the past, like Carl Jung, spoke of the power of myths and stories and shared that they are amazing conduits or mediums in which a society can learn a way of being, the way in which they should conduct themselves, identifying what is considered right and wrong.

For children especially, a straightforward command or demand may not give the desired results – but inspire them through a story which captivates their imagination, well, that effects them in ways they don’t even understand.

So, yes, myths and stories are powerful things.

In Bali, this is no different. Before any real formal education was present on the island, there was one profession that became the moral educator of society. It wasn’t the priests nor was it the royalty, it was the dalang. The puppet masters of Indonesia’s wayang kulit, or shadow puppet, performances.

This theatre style of entertainment is said to have spread to Java as far back as the 10th century, as Hinduism spread through archipelago. It spread to Bali with the fall of the Majapahit kingdom, when Islam spread over Java and the Hindu royalty fled to Bali around the 16th century – bringing with them much of their culture, including the wayang kulit puppet-play.

During a performance, a huge white sheet is stretched across a frame. A lamp (or (blencong) is placed behind, it’s flickering light used to cast the shadows on the screen (or kelir). The dalang sits on one side of the sheet with a dozen puppets propped up in front of him – the good characters to one side, the bad to the other.

The dalang will have assistants left and right who pass certain puppets over to him, and behind him two musicians playing the gender wayang gamelan, which chime in at key moments in the story.

The entire performance is done by the dalang himself. He voices up to 12 characters, each unique in their tone – some low and frightening, other voices shrill and comedic. Bellowing laughs and ghastly shrieks all come from the vocal chords of one man. Simultaneously, he will move several puppets at once, along with their hands that have their own movements.

He remembers every characters line, with up to a hundred storylines he has taken from the Mahabharata and Ramayana epics, or perhaps local folklore too. He throws in jokes, and thus takes on the role of a stand up comedian through specific characters (such as Twalen and Sangut, known clowns). Comedy is key in keeping his audience engaged. At times he sings in Kawi, an ancient language, and speaks in low, middle and high Balinese. He cues in the gamelan players like a conductor.

The dalang is the ultimate multi-tasker, a one-man-band of epic proportions. Half of his audience enjoy the performance through only shadows, the other half sit behind the dalang, to not only witness the story but to see the master at work. A performance can last hours, deep into the night.

Of course, the dalang understands his role in society. The stories he tells will spread religious teachings and positive moral values – all of this is disguised within a flurry of action, drama and comedy that plays out as silhouettes against the screen.

He may tell the story of the God Indra’s own son, Arjuna. Who was put to the test as he meditated at the summit of Mt.Indrakila… he was tempted with beautiful women and threatened by horrific demons. But it was Arjuna’s unwavering belief in the Divine, his self-control and his constant resolve that helped him pass his God’s tests, rewarding him with his famous magical bow and arrow. Perhaps the story acts a reminder for those whose piety is fading…

There are stories of bravery, such as that of Bima Suarga, who follows the archetypal hero’s journey, sent to rescue his father, King Pandu from the depths of hell. The Yudha Kanda, or war story, from the Ramayana is a favourite to depict the battle of good against evil – the same story you see if you watch the famous Kecak dance performance, involving the characters Rama, Sita, Hanoman the monkey king, and Rawana the Demon King.

These are grand stories from Hindu epics.. But the dalang also shares local folklore, often with more domestic morals behind then. Men Brayut is the story of the Mother of Many, who had 108 children, but by raising them all on the teachings of Hindu Dharma, all of them grew up to be wise and pious members of society. A lesson that spirituality is a part of family life, but also that a positive family life leads to better spirituality.

Yes, the list of stories – and the morals and teachings that go with it – go on and on. The Dalang is a compendium of religious knowledge. He knows his role in society, and whilst entertainer is one role, educator is the main one.

His profession is strongly linked with the religious and spiritual. For one, his puppets may tell of sacred stories but they themselves are sacred. They must go through special rituals before being used and are blessed every Tumpek Wayang day, an auspicious day dedicated to Iswara, the Lord of the Puppeteers.

Wayang kulit performances are often done as part of major ceremonies, such as a temple anniversary (or piodalan) or a tooth filing ceremony (metatah). A performance can also be promised to a god when a devotee asks for something; if they do not fulfil their vow (naur sot), calamities will fall upon them.

The type of wayang performance done for religious ceremonies is typically a wayang lemah, performed during the day without a screen and lamp. It is shorter than a wayang peteng (night performance) but is considered a religious act, and tied together with a special ceremony holy water can be produced, called tirta wayang. Thus the dalang is considered a type of priest as well.

Today, the dalang is a rarity. Brought out for certain religious occassions. Children are given formal education at schools now, and communities run to TV, cinemas and YouTube for their evening entertainment.

Whilst the dalang’s role as educator and entertainer has fallen at the wayside in today’s world… this raises the question, without the myths, legends, folklore and stories of these talented puppet masters, who or what, is providing the moral direction of today’s Balinese.