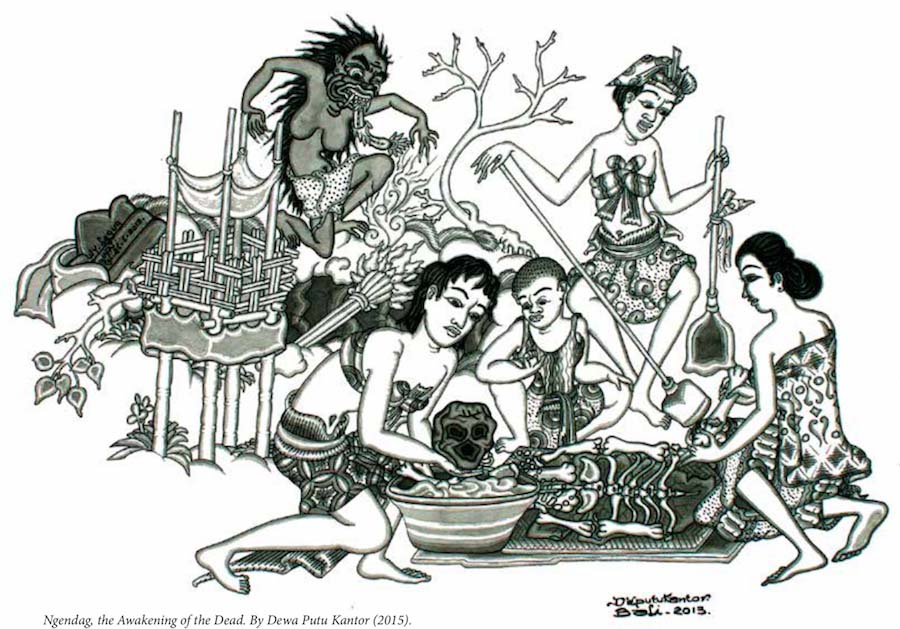

Historian and art critic Jean Couteau brings us stories depicting life on Bali, sometimes real, sometimes myth, always meaningful. Here he shares the story of ngendag , a Balinese ritual in which buried corpses are exhumed to be cremated. This and other stories can be found in Jean Couteau’s book, Myth, Magic and Mystery in Bali .

Ngendag: The Awakening of the Dead

The holy fire is lighted under the holy wood. The man withdraws as the flames rise, enveloping the big black bull that stands erect, golden-girdled, in the middle of the field. The family, all dressed in black, falls silent, mesmerized at the rising flames as the bull is licked away, then the coffin, and finally, what must be the dead.

Fire and pageantry: Balinese cremations are like a show addressed to the world. It is what tourists see at least. But what is the show about? It is about release: By burning the body, one separates the soul from its material envelope, enabling it to “take off” to the abode of the dead. It will then become an “ancestor’s soul” (raja dewata) that will come back during festivals in the family shrine, and later, possibly, reincarnate in a descendant.

The care of the soul and body of the departed, thus, is no light matter. It implies no less than the “circulation” of the souls in the cycle of their lives and deaths.

Not all the dead, though, undergo a cremation right away after death. The richest families, as well as the members of some high-caste groups, postpone the cremation until a propitious day, which is decided by a priest. This might be months after the death. In the meantime, the body lays in state (mesekeh) in the ceremonial building of the house, the bale dangin, and preserved in formalin. The soul, to prevent it from “running wild,” is neutralized by offerings in the nearby sanggar pitra (shrine for the non purified dead). All these require offerings and rituals, and, thus, money.

Few families can afford an immediate cremation, and, a fortiori, a long mesekeh lying in state. Most bury their dead, waiting for a collective cremation to take place at the level of the neighbourhood (banjar) or the kinship group (warga), usually during the dry months of July and August. The body, thus, which has been buried, will have to be dug out and prepared for the upcoming cremation. This is what the ngendag, or awakening of the dead, is all about.

If the dead is woken up, it means that it has “remained quiet” in the cemetery. It would be dangerous indeed to bury a dead just like that, without proper ceremony. This would invite the soul to turn into an erring soul or atma kesasar, the kind that causes illness and disorder among its descendants, and which will eventually have to be “caught” and neutralized. On account of that risk, when someone is buried the family goes first to the Prajapati temple of the dead, where it presents a “notification” piuning offering, entrusting the soul to the goddess of Death, Durga, whom it will faithfully serve (ngaturang ayah) while waiting for the exhumation of the body. The latter is entrusted to the custody of the goddess of the Earth, Pertiwi, as well as, under the watchful eyes of the Sedahan setra, (the guardian of the cemetery) to Surya the sun, as ultimate Witness, and many more. None is to be forgotten, lest the soul runs wild. And there the body will rest for months, or even years, until it is awakened to be cremated.

Months or years later:

An enduring stench and a large field under the eerie shadow of a big kepuh tree. The tree of the dead. There is no mistaking. The stench is that of decomposing bodies. It comes from the direction of a small group of people standing right there, in the middle of the field. A cemetery.

Approaching slowly, you push your way in to see a large hole in the ground with a man fumbling around inside it. Someone is pouring what smells like formalin. The fellow inside the tomb raises his head, smiling. Soon you can see why, even if you don’t yet grasp the purpose of the smile. The man holds in his hand what looks like a small lump of earth. He shakes it; some of the earth falls to the ground, and hair appears.

Only then, do you to understand. The man has just unearthed a cadaver’s head, what might well be, as you will find out later, his mother or grandfather’s head. You have just stumbled on a ngagah ceremony, the “opening” of the tomb, one of the phases of the “awakening” of the dead” ceremony (ngendag). During ngendag, the body will be reconstituted in bits and pieces; symbols of it (adegan) will be made, and it will then follow all the procedures of a “normal” cremation, often alongside recently dead corpses in a collective cremation of dozens of dead.

The ngagah ceremony is ill understood by Westerners, who usually try to keep clear of anything that relates to death. But in Bali death is accepted as a matter of daily life. Instead of avoiding its presence, people involve themselves in every step of its “treatment”. All “first range relatives” are expected to participate in the washing, massaging and perfuming of the body.

During the process, including the unearthing of a half-decomposed cadaver, there should be no manifestation of disgust or grief. “Da kanti yeh peningalan kena ked ke sawa, sang pitra lakar nemu jalan ane belig” – “Don’t let tears touch the corpse,” goes the saying, “lest the dead finds a slippery road to heaven”. Grief is sublimated in rite.

In the casual behavior of the relatives and villagers in relation to death there is more than a mere ritual habit, or avoidance of impurity. Upon death, the soul of the individual (atma) is expected to separate from the body and merge within the cosmic soul Paramatma (or God), while its bodily vehicle, the panca maha buta, blends in their cosmic Panca Maha Buta equivalent –ether, air, water, earth, fire. The whole ritual of death is therefore nothing else than the staging of the separation of the soul and body. By tearing the flesh, crushing the bones and other whimsical treatments of the corpse, the Balinese behave with the body as they do with empty and “demonic” matter: they get rid of it. The fire of cremation is but the next moment in this process. The ashes will eventually be dispersed into the sea and the soul sent to the abode of the dead above the holy mountain.

Yet, if the soul is enslaved by desires, or “hungry,” as people say, it will not blend into the cosmic Oneness of Moksa. It will instead come back “to ask for rice” (nunas nasi) and thus re-incarnate, after it has been through the purgatory of the soul .

This and other stories can be found in Jean Couteau’s book, Myth, Magic and Mystery in Bali .