Outside the building, two young girls are giggling. Above the entrance hangs a big board with the word “Bar” written in awkward letters. Shadows dance as red lights flash on and off to the beat of hard-rock music. Boys are sitting, drinking, surrounded by pretty girls.

Is it a go-go bar? Have the Bangkok lights and shadows taken over Bali? No, not yet, thank God. It is a provisional bar set up by the muda mudi (youth association) as a fund-raising event.

The historical genius of the Balinese has been to create an environment of smooth social intercourse. This special trait is best illustrated by the banjar, a neighbourhood association where the Balinese spend much of their ritual and social life. The banjar not only looks after its members in moments of “joy and sorrow” alike – as put in its name “banjar suka duka “, but it also organizes their participation at supra -banjar level rituals such as temple festivals and cremations. It thus creates an unequalled density of social intercourse.

The youths, called muda mudi or sometimes truna truni , have always been part of this banjar system, either in giving a hand at a village working-bee, standing in for a busy father or uncle, or hanging around the balai banjar collective hall to play gamelan music or just look at the girls.

Until the seventies, however, these youths had no status of their own. They were just in a position of expectation, waiting for marriage, usually to a local girl or boy. Only then, as a married couple (pekurenan) would they obtain banjar and village (desa) citizenship, with its share of rights and duties such as access to land and responsibility for shrines. A youth’s participation in banjar activities was thus marginal. Youth was just a passage.

This situation has now changed. In the last twenty years, all over Bali, in all the banjar neighbourhoods, as well as at the desa (village) level, youth associations, called seka muda-mudi –or seka truna-truni– have sprung up “like mushrooms in the rainy season”. They now play an important role in the running of local banjar or village affairs, particularly in relation to modern matters.

The first youth associations were set up during the independence and post-independence days, when the new generations of educated pemudas – the Indonesian word for youth – spear-headed the independence movement and the subsequent political struggles. This association did not involve village youths as such, though. They were supra-village, national organisations, created to meet the political challenges of the times. Everyone knows what the results were of this politicisation: the 1965 events.

In later years, the generalisation of post-primary education, enhanced by a more stable political environment, completely changed the nature of the challenges. Villages found themselves with hundreds of young, idle, unmarried men and women without any rights or status. The birth of banjar youth associations, sometimes even in the village, was the response to this challenge. Although of recent origin, these associations have now completely blended and been identified with the other village institutions.

The conditions under which and the ways whereby young people become members of the muda-mudi association vary from place to place. Sometimes it is based upon the appearance of the physical signs of adolescence such as menstruation and change of voice, but in other cases it is based on the age, school level or relative maturity of the youth.

Muda mudi associations are run exactly like the banjar and other village organisations. They have an elected primus inter pares head, the ketua, and a small administrative committee complete with a secretary, a treasurer and a messenger. Generally, the association has its girl’s (mudi or truni ) section, patterned on a similar model. This is a big change from the regular village organisations, where the women’s voice is not heard at all. Most associations usually meet every Balinese pawukon month, i.e. every 35 days, although some go by the Gregorian month.

Muda mudi youths willingly lend a helping hand for banjar neighbourhood activities, under the supervision of the klian banjar head. Their role is limited though. They never take part in the religious aspects of the work, such as the preparation of the shrines, which remains the responsibility of the married “citizens.” They may however be entrusted with security and welcome duties or with the holding of non-religious dance performances or fund raising activities. In all of these, the youths operate as a group, training themselves for their future role as banjar members.

Most of the muda mudi meeting time, however, is spent on activities related to youth. The association comprises sections for sports, dance, training etc. In some regions, dance in particular is very important. The youth set up “Ramayana” or “Tari Lepas” groups that perform during temple festivals or even occasionally in hotels. Their dancing is either an “offering” addressed to the village and visiting gods, or a way to raise money for the dance group itself or for other muda mudi pursuits, such as embroidery courses or English lessons amongst others.

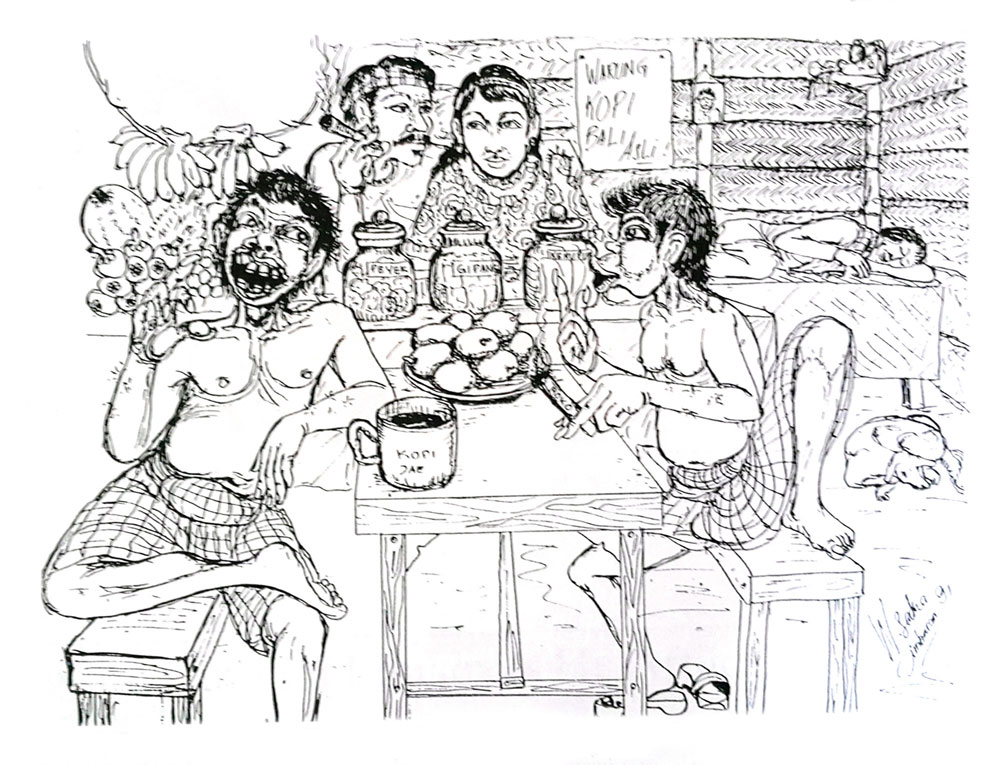

Their favorite way to raise money, however, is by holding the so-called bars or fund-raising parties. The girls prepare the food and organize the welcoming committee, while the boys look after the security and the general running of the bar.

Invitations are extended, which are difficult to refuse, or at least, if one is wary of one’s image in the village. Prices are inflated, but that is expected, since holding a bar is one of the ways to raise money for the group. Good humor and good clean fun prudery is the rule, although the atmosphere is one of deafening pop music and red lights.

One of the side attractions of the bar is also to get to know the young people from neighboring banjars and villages. They are usually invited in turn, one muda mudi association after the other, and all are keen to come. The purpose is obvious. It is a chance for the boys and girls to get to know each other. Since the invitations are formal, and the security tight, the behavior of everyone is generally very correct. To misbehave would bring shame not only on the person, but on the whole invited group. In this way, village youths manage to broaden the range of “mate-hunting” while keeping risky “accidents” to a minimum.

The muda mudi association has internal controls over its members as well, although it is less formal, since a local “scoundrel” can always be caught and compelled to marry the girl. Usually a regular late night visitor of a girl from the banjar will be revealed so that “everyone knows”, and thus, is warned and even threatened. Some youth associations with help from the banjar even go as far as enforcing “night curfews” or limit the hours of visits, lest one is compelled to marry. But shame and embarrassment usually suffice to check the wanton ways of the boys.

If the liaison does end up in a marriage, as expected, members of the muda mudi organise a special visit, present a gift, and then the bond is severed: the new couple will now become full banjar citizens.

In Bali, adolescence is a smooth passage into adulthood. Much of this is due to the muda mudi association.