The first thing one notices in the shadows of the dimly-lit temple is the mysterious mumbling of human voices, which is not quite that of a chant, but not quite that of normal conversation either. If one approaches the bale (open pavilion), one sees a small group of men, sitting in the lotus position around a short table, on which lies a book or a long palm-leaf manuscript (lontar). All are dressed in Balinese fashion with a sarong and udeng (head-dress). On the low table in front of them, a stick of incense can be seen burning inside a “basket” of canang (offerings), near a betel-chewing set.

One of the men, leaning forward over the text to decipher its words, launches himself into a long recitative (mewirama). He stops, and the man next to him starts speaking out, emphasizing slightly the last words of his sentences while looking around for approval from the other men. He has barely stopped when a third man starts what looks like a speech.

These three men have performed the three phases of the reading of the kakawin, the famed poetry in Kawi language handed down through the ages from the golden day of Hindu-Java. The first one was singing the Kawi text, the second was translating it into Balinese (ngartiang), while the third one was commentating on it (maosin). These men are the village participants of a reading session of kakawin. They are among the last bearers of the threatened Kawi language.

The Kawi language was brought to Bali from Java in the course of the centuries-long contact between the two islands, and particularly after the Javanese invasion of 1343, which turned Bali into a stronghold of Hindu-Javanese culture. Adopted as the language of Balinese courts, this language survived until modern times. Balinese men of letters were still writing in Kawi until the beginning of the 20th century, while it disappeared in Java following the Islamization of the island in the 16th century.

Kawi illustrates the resilient influences of Indian culture in ancient Java and in Bali. Half the vocabulary of Kawi is of Sanskrit origin and the characters are derived from a South-Indian writing. Most stories also have directly or indirectly evolved from Indian myths and epics.

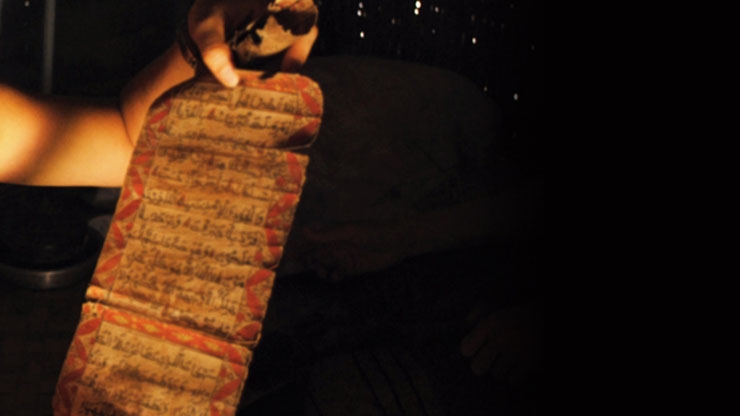

Until recently Kawi literature was exclusively written on, and read from palm-leaf lontar manuscripts. Few people nowadays use this medium which is deemed to be too fragile and too difficult to read. Characters sometimes look alike on the palm-leaf and thus are often confused with each other. It adds to the intrinsic difficulty of the writing, which doesn’t separate one word from another and which has very little punctuation.

Most Balinese can only read their own family manuscripts, which have a distinctive handwriting and on which they have practiced reading over and over again. Nowadays, however, manuscripts have been substituted with books, written in standardized characters that considerably facilitate reading.

The rhythm and pitch of kakawin reading, called makakawin, is determined by a metric system that consists of combinations of long (guru) and short (lagu) syllables, which are identifiable by their Balinese writing.

The reading of kekawin poetry is not the only time that Balinese still use the Kawi language. Kawi is also frequently used in ritual mantras and in the theater, particularly in the puppet theater (wayang). Typically, the noble protagonists speak Kawi and their courtiers and servants translate their words into Balinese.

This system provides a popular way of teaching the language, but it also accounts for its alterations, as the “theater-Kawi” is strongly enmeshed with Balinese words and structures. As a matter of fact, few Balinese have a knowledge of Kawi beyond a few theatrical sentences.

The reading sessions of Kawi poetry are a good illustration of the traditional teaching techniques. There is no such thing as compelled rote-learning, or an analytical approach. The newcomer to kekawin poetry, who usually has a basic knowledge of Kawi as it is used in the theater, begins his “lessons” by attending the reading sessions. Listening to the same repeated texts and sentences, he “learns” them, little by little, without any apparent effort.

One day, preferably when he is “mature” enough, he will move closer to the readers of the manuscripts and sit in the outer circle of readers. Later, he will eventually be given a chance to read with those of the inner circle. Knowledge gained, thus, does not result from a painful process of “study,” but from patient attendance, and from socializing with the men of letters, at the right time and in the right place.

Attendance is usually open to all, which does not mean that all have the same place and role. Kawi reading is more widespread among the upper castes, particularly among the Brahmins, who are the keepers of the most sacred texts and own the most complete lontar libraries.

To gain acceptance to the kakawin reading sessions of these groups, the outsider is expected to display a disciple’s (sisia) behavior. In other words, he must acknowledge his status as a dependant. The organization of the reading session depends on the reader of the highest caste represented.

The seating arrangement of the participants displays both their knowledge and their status. The kakawin masters occupy the inner circle of attendants, with the newcomers occupying the outer circle, unless their status allows them otherwise. If the reader is a beginner, he approaches the table to read but, as soon as he has finished reading, he slips back to his former position. After that, it is the turn of the translator, who usually sits next to him. The latter rarely knows the text word by word, or its grammar, but he knows its general meaning, having heard the sentences repeated so many times. After the translator comes the turn of the commentator, who gives the exact meaning of the words or, all of a sudden, launches himself into a detailed philosophical explanation on the meaning of the poem.

These three roles, reading, translating and commentating, are interchangeable, if talent permits, and there are often several people available for each, making up a total of twelve or fifteen people for a normal makekawin session. Usually the “higher” one’s status, the more one is expected to participate, and the more one’s comments are regarded as perfect and definitive. This system ensures an efficient diffusion of knowledge while keeping the control of the “ultimate” knowledge in the hands of the high-caste groups.

In the makakawin reading sessions, not all classical texts are studied, and for a good reason. It is not the Kawi literature itself that is the object of the study, but certain texts themselves which are endowed with mystical and symbolic values. One is never asked if one knows Kawi, but rather if one knows such and such a part of the Ramayana, the Sutasoma or the Siwaratikalpa, that are used during ceremonies.

To give an example, during a cremation ceremony, one reads an excerpt from the Bharatayuddha in which the five sons of the Pandawa brothers are killed and cremated. Reading re-enforces the ritual. In this sense, the study of literature in traditional Bali is inseparable from religion.

The reading of kakawin during ceremonies is not very different from ordinary reading sessions. Excerpts are chosen which “masters” or their invited friends and favourite “disciples” can only recite. The environment is more formal, with gifts of food, special reading quarters etc.

The reading group (pasantian) meets at regular intervals such as once a week or each full moon and new moon, or also during the nights of temple festivals. The sessions take place on one of the verandahs (bale) of a temple or in an individual’s house, preferably a brahmana mansion. These pesantian groups are usually set up with a limited religious purpose, as explained above. One or several masters, preferably brahmana, are invited to “teach,” and the villagers are invited to participate. Once the goal is reached, i.e., when the “useful” texts are known, the group dissolves or meets more irregularly. Permanent groups are active among Brahman and princely circles.

What is the future of Kawi and kakawins? We must recognize the fact that the “cultural memory” of the Balinese is being overwhelmed by modernization. The reading of kakawin, as well as later Middle-Javanese kidding, is now strongly encouraged by the authorities; but the emphasis is put on the reading and singing rather than the meaning. Therefore, like all Balinese oral traditions, poetry reading in spite of recent revival, will probably go down the drain or become a niche, identity related activity.

What will fill in the gap? Television, I suspect.