The ancestors’ cult, for some reason, is deemed irrational. Is it for this reason that established religions are doing their best to eradicate it? Indonesia is a case in point, regarding both Islam and Balinese Hinduism.

In Indonesian Islam, the main point of contention between the two principal Moslem organisations, Mohammadiah and Nadhadul Ulama, is centred on the cult of the Moslem saints, the wali, and the offering to the petilasan ancestral tombs scattered about the land. Are the faithful allowed to address God through the intercession of holy men’s tombs? No, say the Mohammadiah and other rigid followers of Islam (Wahabi, Salafi). Yes, say the Nadhadul Ulama and traditional Javanese peasants, who never pass by a tomb in the forest without a short prayer. So they quarrel, but, as education improves and people learn to decipher an ever holier Holy Book, beards grow, the veil becomes the norm and holy men disappear from the cult, ancestors’ tombs with them.

Regarding Bali, the question is: are we going to witness a similar phenomenon. The answer is not easy to give, but, from the evolution under way there is little doubt that from the “front seat” the ancestors’ cult now occupies, it will soon be relegated to a “back seat”.

What is actually going on? If you ask Balinese junior high school children what is their religion, all of them will reply “Hindu”. Yet, the word “Hindu” is a new word in Balinese society. It was introduced by British and Dutch scholars of the 19th century after they found common points between Balinese brahmanic texts and the texts they had previously viewed in India.

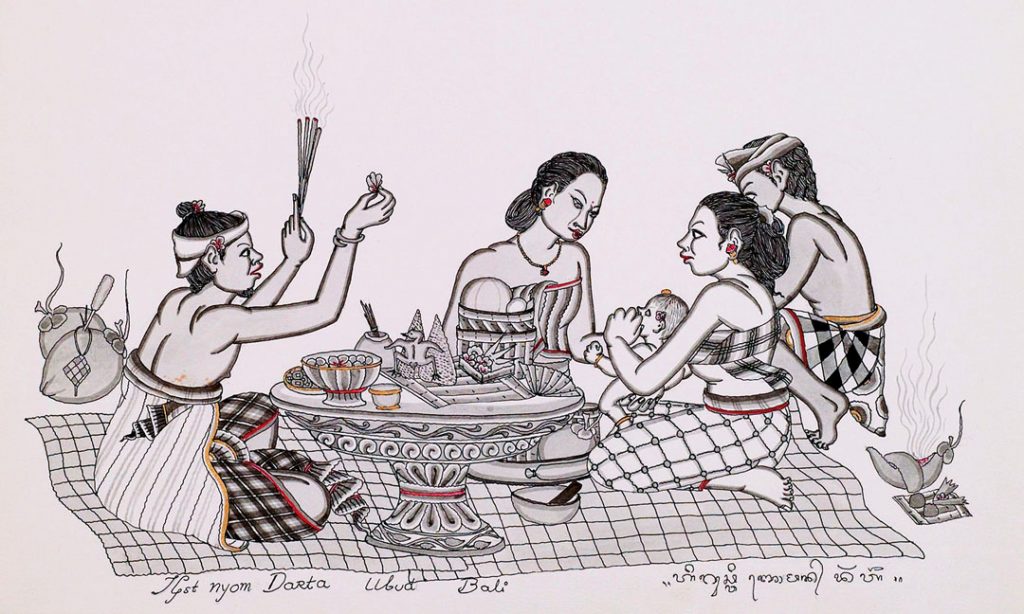

Yet, don’t believe that Balinese traditionally worship the likes of Ganesha, Rama or Krishna. The only ‘gods’ they know they are worshipping are their ancestors. They call them by their name, ‘Kaki/Nini’ (grand-father/mother) on a personal basis during their daily prayers or during temple festivals, when those ancestors come on visits to be welcomed with dances and offerings. The main objectives through the lives of a Balinese is traditionally to help those ancestors come down from their old country (tanah ane ayah) above the mountain, and re-incarnate: finding a partner and making love has no other purpose as to facilitate the ‘coming down’ of a waiting ancestral soul to come down ‘as a drop of water’, or titisan. And the death rites do not end with the world-famous Balinese cremation. They are complete only when the soul has been definitely separated from its earthly envelope and delivered ‘for good’ to its place of origin, above the mountain. All Balinese clans have temples at the foot of Mount Agung or Mount Batukaru for this purpose. There, on completion of the rites, the dead are said ‘to have become water’, (suba dadi yeh). He/she has now become a full-fledged batara, a god, ready to grant protection and benefits to their ‘children’ (cening). Ready as well to reincarnate when its time has come, if the door is open. Because downstairs, where the humans dwell, there are indeed men and women who are making the next incarnation possible: by making love – ideally after beseeching an ancestor to come down at the family temple (nakti). No surprise therefore if a new-born baby is usually called ‘I dewa’, or (little) god, as he/she is an ancestor who has just come down. This ‘little’ god, if a boy, will later play a prominent role once he has become an adult. He is the ‘heir’ (sentana) who will look after the ancestors in the family temple, as well as send the souls of the dead to where they belong. So it is important to know who is ‘coming down’. After birth, one of the main rites is to visit a medium, who will ask the soul who it is and whether it has a specific request.

Under such conditions, it is easy to understand that the worst thing that can happen to the departed, and especially to their soul, is to somehow fail to be properly sent to “the old country”. This is why people avoid crying during the rites of the dead. Any mistake can derail the whole process. If so, the soul will lose its way (atma kesasar) and wreak havoc among the careless descendant. Illnesses and accidents unavoidably ensue… Which only a medium will identify by calling his down.

What about the Hindu gods? They are nowhere to be seen in daily religion. When the traditional Balinese address any other god than his/her ancestors, the god’s name is usually indefinite: Sesuhunan, Ratu Gde, to which is often added the name of a place. It is of little importance. God does not have to be defined. It has as many names as he has place to “sit” (linggih).

Yet, Hindu gods and Hinduism are nevertheless increasingly present. They appear in the mantras uttered by the Brahmin priests. They are mentioned in literature and the puppet show theatre. Following their transfer from Java in the times of yore, according to the Pasek Chronicle, they now hover over the Balinese mountains. They never come down in a trance and one never addresses any prayer to them. They are “somewhere else”, ruling the cosmos rather than Bali.

Yet, things are changing. In the old days, outside the odd Brahmin priest yearning for moksa, the Balinese always reincarnated among their kin, in other words they returned. So, reincarnation in a non-human form applied to gods, heroes and villains, but not to the Balinese peasant, who was eager to come back “asking for rice” (nunas baos). Even though its notion existed, it remained ill-defined. Why, because there was no theology, no need to really “structure” the notions of God, Nature, the soul the presence of humans and their place in the universe. There was syncretism, but of a peculiar type, corresponding to the sociology of the land: the Brahmins and lettered princely circles had adopted half-formulated Indian cosmogonic concepts that remained alien to the ordinary peasantry.

Today’s reinvention of Balinese religion as fully Hindu under the name of Hindu Dharma is transforming the land. God is named as such (Sang Hyang Widhi). The gods are only His “manifestations”. The soul now transmigrates according to its accumulated karma, and it is supposed to aim at achieving moksa, and eventually melt into the ultimate Oneness (moksa). In such circumstances, where are the ancestors? Lost among the manifestations of God above. They definitely recede in status, don’t they?

Yes. When the ‘memory of old’ is withering away and religion becomes overly rational and serious, the risk is that it morphs into identity and politics. It is now happening to Hinduism in India. When will it be the turn of Bali? Let us hope it does not come.