If you are living in Bali, or have often visited the island, you may not know the man, but you are likely to have seen his wonderful photographs of some of the most secret rites and ceremonies of Bali. This photographer’s name is Gustra, or, in its full brahmana name, Ida Bagus Putra Adnyana (64). A smiling, open-minded man, always on the search of new images, new experiences and new friends.

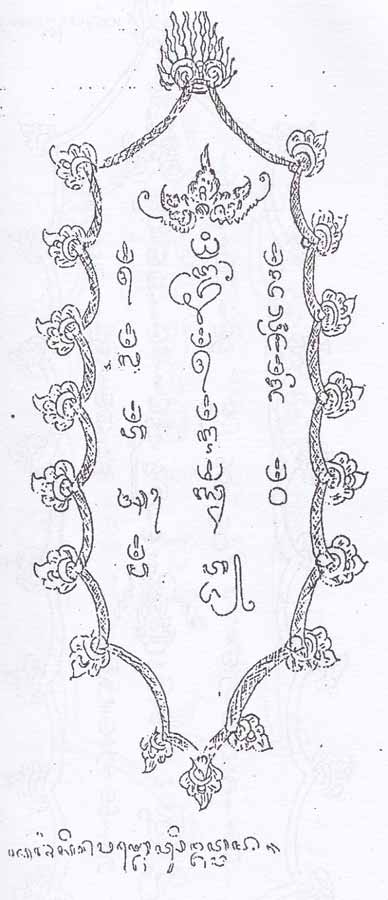

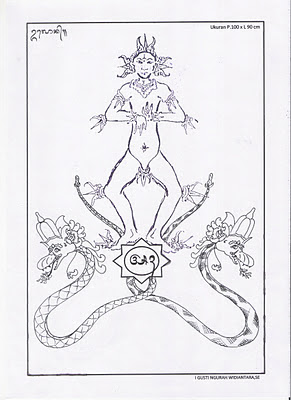

“Do you know what took me to photography, Jean?” asked Gustra, in one of our many discussions. “It is drawing. I was born in a milieu in which drawing was at the very core of our daily activities. And don’t think it was because my father was a painter. No… my parents were brahmins, and the main job of my family was to make sacred drawings, in particular the kajang, the death shroud one unfurls on to a corpse before cremation.”

Now, that is quite the introduction to the art world. I knew that high pedanda priests are sometimes accompanied by brahmana assistants, but it never came to mind that drawing was part of their job. Drawing on a shroud of cotton the esoteric symbols, sacred letters and magical figures that accompanies a cadaver to be burned together in fire, which enables its soul to continue on its way to the ‘old country’ of the dead.

“So, your first training in the art field was related to death then?” I asked him. “Yes, Jean,” he replied. “And it was not an easy job. The kajang put on the laying corpse before cremation differ according to the dead person’s clan. There are hundreds of types.” For those who do not know, the high-priest is at the head of a whole system responsible for producing rites, holy waters and related implements, including these sacred images. A mini-economy of the sacred.

Gustra, through his family, “bathed” in Balinese tradition. But he also lived in the city, where cars could be seen, military paraded and tourists roamed. At school, well trained by his kajang skills, he excelled at drawing. But modernity was there too: his father bought him a simple plastic camera, and, before long, the magic of images was at the tip of a click. Yet, becoming a photographer was not an easy achievement. There was a segregation of sorts. Money was scarce. Cameras were expensive to purchase and to maintain. All the local photographers at the time were mainly Chinese, owners of shops and workshops who made photographs during their free time or in studios. Gustra knew a few of the latter, he would assist in preparing wedding shots and studio photos, and they would lend him their equipment in return.

Gustra also improved his techniques by participating in photography competitions. He would win prizes, the money of which he used to purchase ever higher quality material. With it came new photos, new prizes and new cameras. And better and better photographs.

Until the late 1980s, the good jobs normally went to foreigners who came to Bali already on contracted assignments from big western magazines. They had prestige. For the local Balinese, the best jobs were still weddings, public events and other more fringe requests.

Gustra, still a youth, had other ambitions. He wanted to be an artist, but his father objected, and he took a law degree. This did not get him a bureaucratic job. Meanwhile, tourists were now coming in droves. Among them were more western photographs who needed assistants. It meant jobs and new opportunities. Gustra perfected his technique and in a few years, beginning in the mid-1980, he had a successful postcard business, and was systematically building up an extraordinary visual documentation of the island and its culture, with photographs published in magazines.

Gustra was originally at a disadvantage compared to foreign photographs. They were masters of their craft, had top-of-the-range equipment and also knew the market. This could create sensitive situations, as Gustra explains: “Sometimes, especially in the past, these visiting photographers would think they “owned” the field. They would order other photographers, including me, to move aside, because they had to make “their” shots of the “unique” things they wanted to immortalise. When I was their assistant, I had to tell them to quiet down. But it depended person-to-person, of course.” Gustra adds, with a smirk: “Yet, even when pushed aside for the sake of a shoot, the Balinese would usually continue to smile. They are used to respecting their guests.”

Such remarks are revealing. Photographers can misbehave: turning other people into visual objects, they focus only on the image, at the expense of everything else. It ends in a paradox. They make their name about things they show, but the meaning of which they ignore, and they are celebrated as connoisseurs of the land and people they themselves have exploited.

Gustra was all the more aware of these issues. His position and attitude are very different. Regarding the Balinese, he is one of them. He knows the culture the rites of which he is photographing. So he often knows what is going to happen and its meaning. Even though he never boasts about it, he is a Brahmin, and is as such respected wherever he goes. He himself respects the rites that he immortalises through his own photographs. He most often knows their function. He can gain access to ritual moments out of reach to foreign photographers – access available only to a Brahmin, and thus, he becomes a window into scenes others are simply not privy to.

Still better, he has networks: little traders, market handymen, flower sellers, who give him the tips about upcoming festivals or cremations in remote places. Once he has the information and knows that the ceremony is a unique one, there he goes, to come back with new shots. Sometimes fantastic ones.

Thus, Gustra’s endeavour is not to make a name for himself in foreign lands. He remains humble. “What I do is mostly documentation,” he says. “Yet, I have often to go beyond the ordinary, and it is probably then that I do my best shots, when I really use my “eye”. It might be a high priest in prayer, a set of offerings or a unique dance from east Bali.” Most of the time far from the ordinary, and often exceptional documents, both beautiful and unique. When one asks him about his works, he says, “I have tens of thousands of pictures”, he explains he has no less than thirty terabytes (that’s 30.000 gigabytes) of digital memory with photos from Bali. Many are so uniquely beautiful but he forgets them in the depth of his computers, to better rediscover them at the request of a friend, like me. His works are a genuine treasure trove.

Gustra is somewhat skeptical regarding the future of photography. He has probably seen and photographed the most visual moments of Balinese culture, that is, during an extraordinary period where old tourism money generated a blooming of the most extravagant rituals in the 1980s and 1990s. Much of it remains, of course, but the best days are gone, as beauty is now eaten away by plastic, vehicles and modernity in general.

So, now, Gustra has shifted his attention to his old dream: becoming a painter. He says that painting helps him develop a better understanding of composition and colour. One of his works was recently selected for an important art event. He also makes contemporary digital photography.

Yet, when I think of Gustra, I think of the friend who, single-handedly, has built the most extraordinary documentation on Balinese culture. A documentation that would be the envy of museums in Bali and around the world.