Gung Lingsir, the old prince of Abian Gombal, was now back outside, sitting cross – legged on the verandah of his old pesaren pavilion. He was lost in thoughts. He had had a near call with death, but now, with the fever gone and having lost a few pounds, he could once again run the affairs of his state. There had been a big exorcism to cleanse the grubug (deadly epidemic) from the land, and send back the evil spirits to where they belonged. Again on track, the mekel (village heads) were bringing him his due share of the crops, and the patihs (ministers) patrolling the border of the land.

But Gung Lingsir often recalled the hand, which had kneaded his head in the worst of his throes, when all the priests had failed, despite their magical concoctions and prayers. He was well aware that he owed his life to Nang Oblong, the balian (witch doctor) from Dauh Pangkung, and thus he had summoned him to the palace.

He was thus still sitting, slowly massaging the scraggy limbs of his champion cock, when he saw a man approaching with one of the patihs, his hands clasped, bowing repeatedly. It was, as expected Nang Oblong, the balian. The old man glanced at his lord and then, bowing again, sat on the lower steps, his hands clasped, waiting in awe.

“Kene, Blong,” started Gung Lingsir, stopping a while to spit out the tobacco he had kept under his tongue,” you are old and poor, with seven sons to feed. But it is through your help that the Batara (god) has shown mercy on me. I thus want your family to be bound to my house. Listen, Blong, all the land belonging to me to the North of the river I bestow upon you, as long as you and your sons have heirs, and as long as you remember your duties toward my puri (princely house).”

This is how Oblong knew that he had had land given to him. He had thanked the prince profusely and had taken possession of the place. His Lord’s word was law, and Oblong did not feel the need, nor did he dare to ask, to have his lord’s will written down on lontar palm-leaf, as he knew a brahmin had done. He believed in his lord.

Since then, each time there was a summons, they were among the first, he and his family, to show up, be it to contribute bamboo for the building a of ceremonial platform or for a show of force at the border of the state. Oblong had become a faithful parekan (dependant) of the prince.

Then the old prince died, and later so did Oblong. His sons carried on their duty. “We belong to the puri,” they would say, and thus were faithful to its prince. According to their talent, and upon their prince’s request, one would teach dance, another carve the doors of a restored building, a third one would have one of his daughters living at the puri and all gave bamboo, rice from the crop and indeed free labor.

These were the ways of the time. A “feudality” balanced by a strong network of interpersonal bonds and exchanges.

Then came the Dutch and independence. The land was registered at the Land Office. Pipil (indigenous tax registration papers) were made in the name of the prince, but on the ground nothing had changed: Oblong’s great-grand sons still used the land and still paid their duties to their princely lord. More recently, however, came the time when the sons of the prince were no more prince of a village, but city dwellers. One was the head of a bank in Denpasar, another a high official in Jakarta. Only the old Gung Lingsir was still living in the old puri of Abian Gombal. He was the last one in the palace who still knew the “rights and duties” between his house and Oblong’s descendants.

Then, he died. Upon his death, Babler and Kocong, Oblong’s great grand sons, again showed up, faithful as ever, collecting the bamboo and helping to build “their” prince cremation tower. They felt they “belonged” to his house.

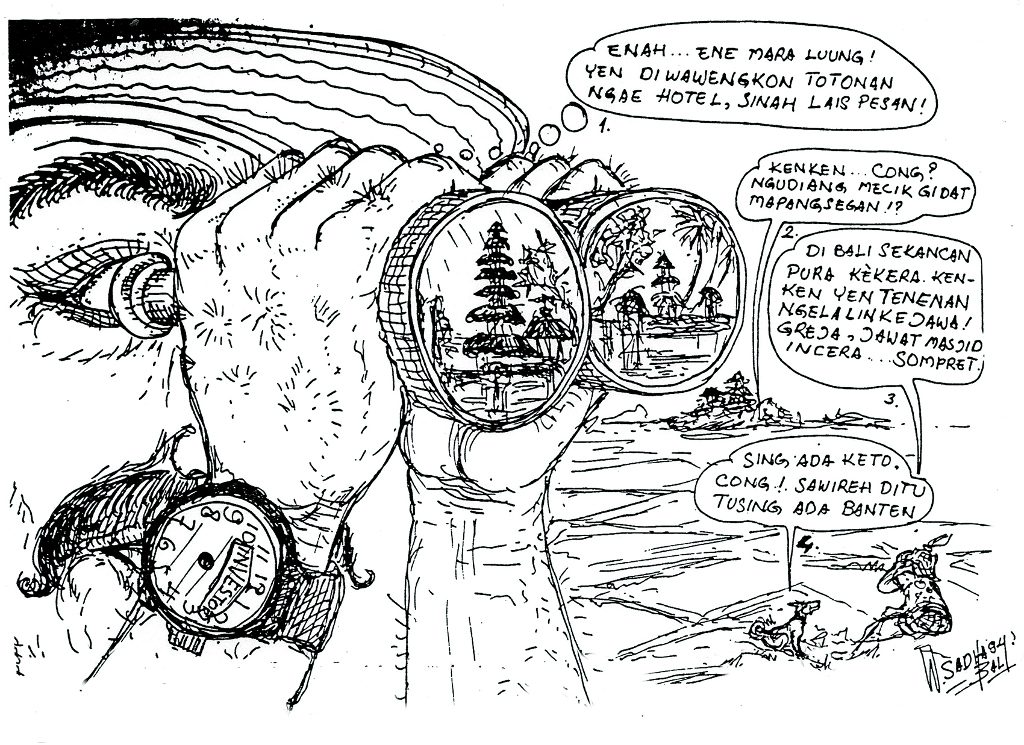

Gung Anom and Gung Putra, however, did not see themselves as feudal princes anymore, but as modern businessmen who wished to invest in tourism. They still felt good to be treated as lords whenever there was a ceremony in their village of origin, but for the rest, they relied on modern law and contracts. They believed in “papers,” while their fathers had believed in oral engagements. Now these engagements were perhaps still valid to Babler, Kocong and old village people, but they had no legal value. So, when, upon their father’s death, the two princes shuffled through his papers and came upon the old pipil of Oblong’s land in their ancestors’ name, what did they do? They considered this land to be theirs. And they decided to sell it. Thus, Gung Lingsir’s gift of land to Oblong, which had had force of law for perhaps 200 years, was suddenly voided of all content. Babler and Kocong found themselves suddenly landless.

Did they protest, did they go to court. No! To go to court and attack their princes would have run against their tradition: what the prince gives you, the prince can take away. To protest would have been a betrayal toward pongor kawitan (the ancestors).

There have been more than a few Oblong and Gung Lingsir in Bali. And there are many Gung Anom and Gung Putra. As land gains value and becomes a commodity, and as the old communal and feudal bonds weaken, old “promises” and “rights” lose their power of law or are just forgotten. Sometimes, the self-righteous heirs sue and expel the occupants of “their” land; at other times, they acknowledge the “service” performed by their former palace’s dependants and compensate them. Only one thing is certain: Money is wreaking havoc upon what remains of the old social structure of Balinese villages.