The bird of paradise, Cendrawasih in Bahasa Indonesia, holds a special place as a symbol of New Guinea and Indonesia, drawing visitors from around the globe to witness these majestic birds in their natural habitat on the second largest island in the world. However, for centuries, these birds remained as mysterious as the prized spices from the Far East, now Indonesia.

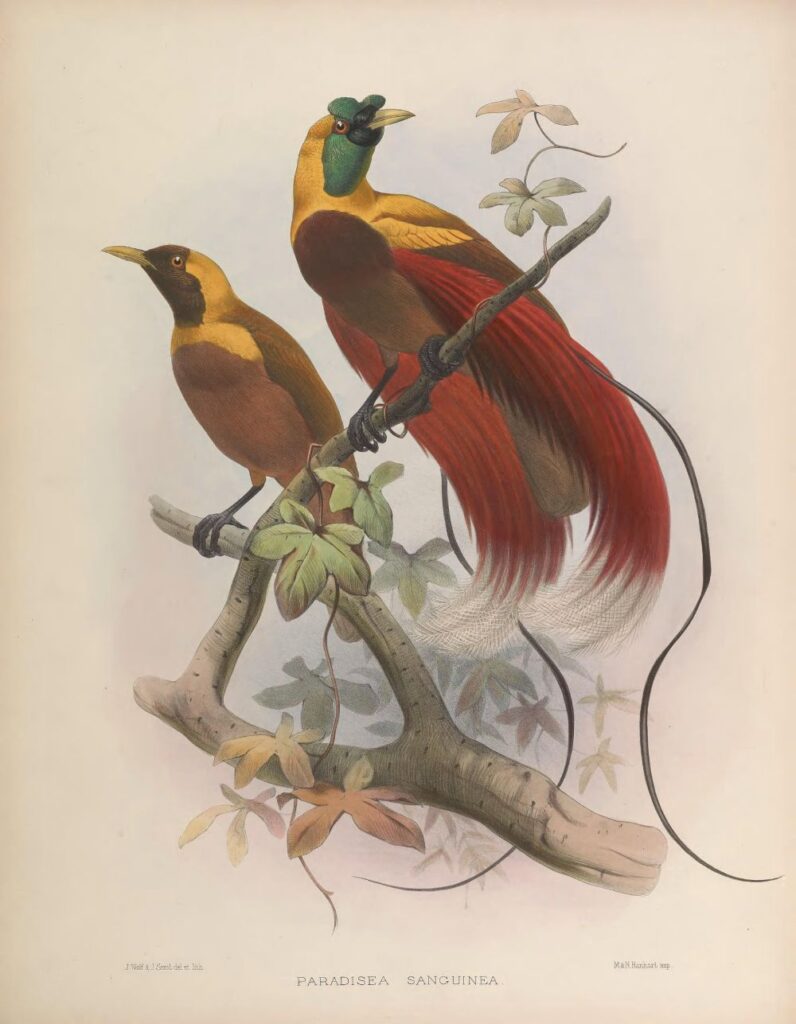

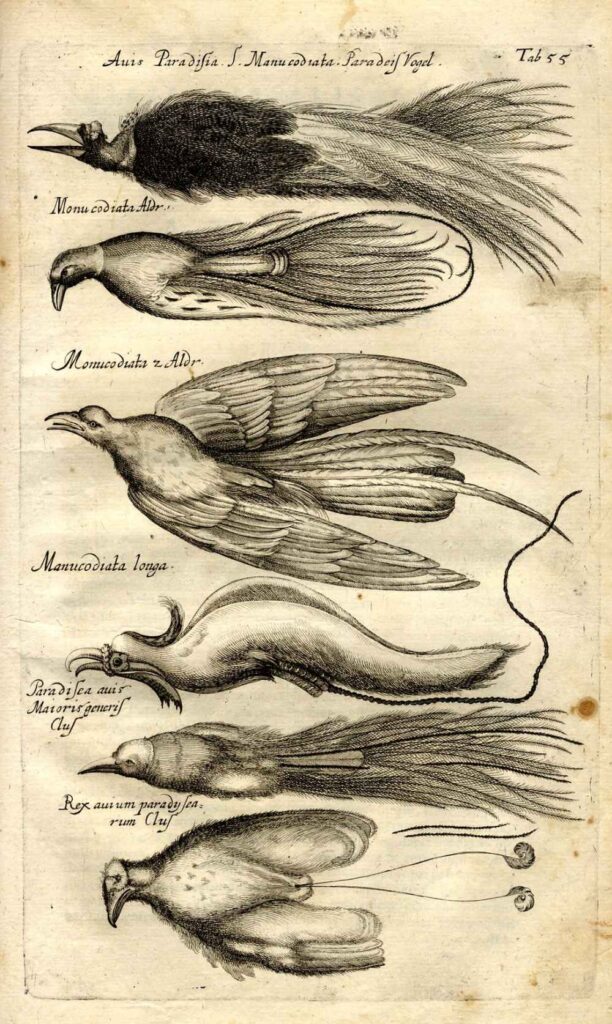

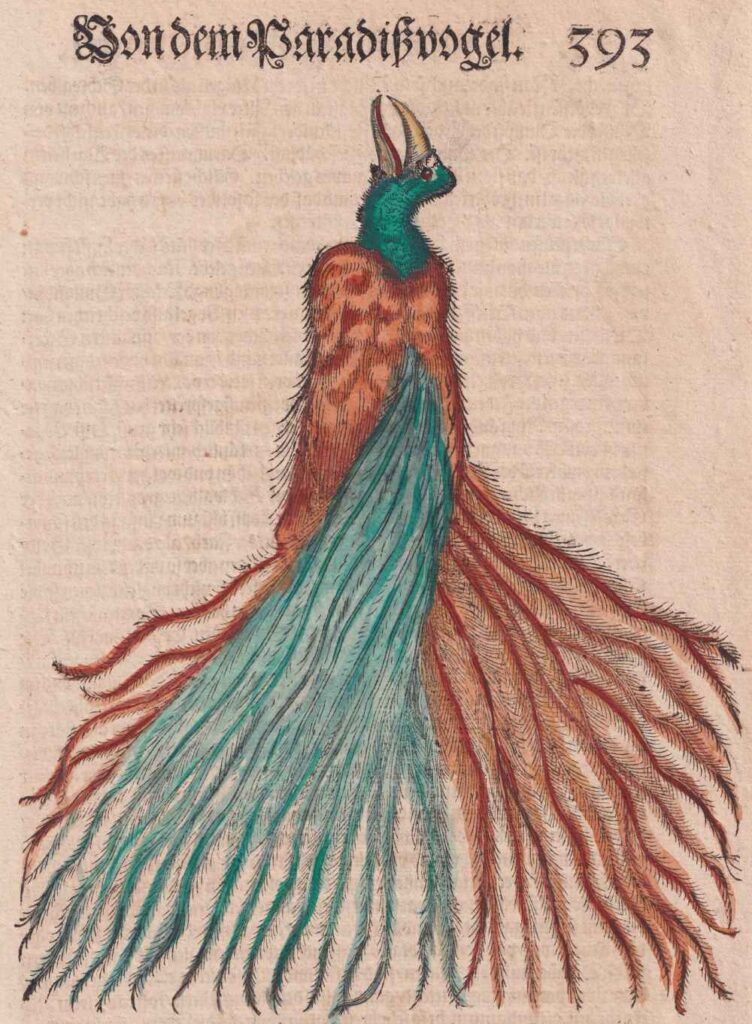

Sake Santema, from Indies Gallery, showcases a collection of his antique prints featuring early depictions of birds of paradise, some dating back over 450 years. These prints offer a unique insight into how naturalists of the 16th to 19th centuries sought to unravel the mysteries surrounding these exotic creatures, floating perpetually in heaven, feeding on dew.

Bird of paradise plumes were some of the most desirable products in Asia and had been part of Asian trade networks, which circulated spices and other valuable goods such as ivory and textiles, for at least 5000 years before Europeans discovered the region in the late fifteenth century. When birds of paradise first arrived in Europe, as dried specimens with legs and wings removed, they were viewed in almost mythical terms.

In 1522, the dismembered skins of new and fabulous creatures were brought to the court of Emperor Charles V of Spain with a cargo of spices, such as cinnamon, cloves and nutmeg, from a fleet that had left in 1519 to circumnavigate the globe under Ferdinand Magellan. These unusual skins were shrunken and wingless, causing their beaks and gorgeous plumes to be disproportionately exaggerated. They were prepared by New Guinean hunters for tribal dances and displays, which still occur in areas of New Guinea. The flesh and limbs were removed, though methods varied by tribe and species of bird, and the whole skin was smoked to heighten the dramatic effect of the elaborate feathers.

Very little was published about these rare birds until the middle of the sixteenth century. Even so, it didn’t take long for their depictions in books of emblems, natural philosophies, and in many other genres to transform them into angelic, floating creatures. These images were based in part on the Islamic myths published by Transylvanus and the fact that the “Orient” has been seen as an exotic paradise full of wonders and riches for hundreds of years. It was almost no surprise that the East should turn out to be a Paradisal land full of spices and jewel-like birds.

Yet the living birds were virtually unknown to anyone outside New Guinea, even to the Moluccan traders who dealt in New Guinean products. One Portuguese trader who travelled around Southeast Asia wrote in 1513 that birds “which are prized more than any others come from the islands called Aru (Daru), birds which they bring over dead, called birds of paradise (pasaros de Deus)”. The skins, most of which bore the iridescent green and velvet brown plumage of the greater bird of paradise were prepared for trade, limbs removed, and rapidly acquired by European aristocratic curiosity collectors.

In order to form a complete history of the birds, Gessner brought together as many sources as he could. He included one of the first scholarly descriptions of a bird of paradise, found in the expansive De Subtilitate (1550), a book by the Italian mathematician and astrologer Jerome Cardan. Cardan reasoned that, because these birds were never seen alive and could not land without feet, they must exist perpetually airborne in the highest reaches of the sky, and live on air and dew.

On the basis of these and other accounts, Gessner developed some ideas about the life histories of the birds. He suggested that these “Lufftvogels” (birds of the air) were effortlessly suspended by their haloes of plumes. Gessner imagined several uses for these hair-like projections, or cirri — the naked shafts projecting beyond the rest of the feathers. He speculated that the birds might use them to hang from tree branches when they were tired. They might also be vital to the birds’ love lives: Gessner envisaged couples entwining their cirri together when mating, and as the female sat atop the male to brood her eggs amongst the clouds.

Jumping forward, in the early 19th century, expeditions embarked on a quest to study these elusive birds. One notable expedition was led by René Lesson, a French naturalist, who conducted extensive research on these birds in their natural habitat. During his 1824 visit to New Guinea, Lesson became the first European naturalist to observe birds of paradise in the wild. This culminated in the publication of the first and most comprehensive book on birds of paradise, “Histoire Naturelle Des Oiseaux De Paradis” (Natural History Of Birds Of Paradise), authored by Lesson in 1835. His subsequent publication provided a comprehensive summary of the species, complete with detailed descriptions that shed light on at least four previously unknown species to European naturalists.

The antiques shown in this article are offered for purchase by Indies Gallery, dealer in authentic maps, prints, books and photographs, dating from the fifteenth to the twentieth century: www.indiesgallery.com

Indies Gallery also offers these decorative art works as reprints. You will find these at www.oldeastindies.com