Bali’s tourism industry seems to constantly be at a challenging crossroads. A perpetual tug-of-war between tradition and modernity, pulling at each other from opposite sides. Though ironically, both are equally necessary. It is rwa bhineda, the Balinese philosophy of duality, at work.

Tourism has been growing for a century and despite how much of a double-edged sword the industry may be, it has certainly brought prosperity to the island. In that time, Bali has endured an evolution, both in environment and society, and its increasing interaction with the wider world has been a direct cause of this. Yet, with 70-80% of its economy still dependent on the industry, finding the right ‘balance’ remains a necessary goal. Whilst many think into the future to figure out the right path, some inspiration lies in the past.

Since 2019, Radit Mahindro has been chronicling the long and intriguing development of Bali’s tourism industry. This began as casual-yet-passionate archiving on a blog and Instagram, focused predominantly on hotel architecture and design. Passion turned professional and widespread interest has resulted in Radit and partner Krisna Sudharma landing a book deal, set to be published in 2024.

The title of their project, ‘Paras’, has multiple meanings in Bahasa Indonesia, it can be translated as ‘face’ or ‘surface’, ‘stone’ or ‘limestone’, and ‘even’ or ‘balanced’. Thus it simultaneously refers to how Bali is perceived, its built environment and culture of creation, plus the need for harmony on the island.

A sojourn around Bali’s most popular tourist areas will make us question all of these important components. Infrastructure lacking and identity undefined, with every region presenting its own ‘character’ and own version of the tourist experience. From Ubud to Uluwatu, Tabanan to Sanur, there are few common threads that run between them. The ‘face’ of Bali is a mosaic and a confusing one at that.

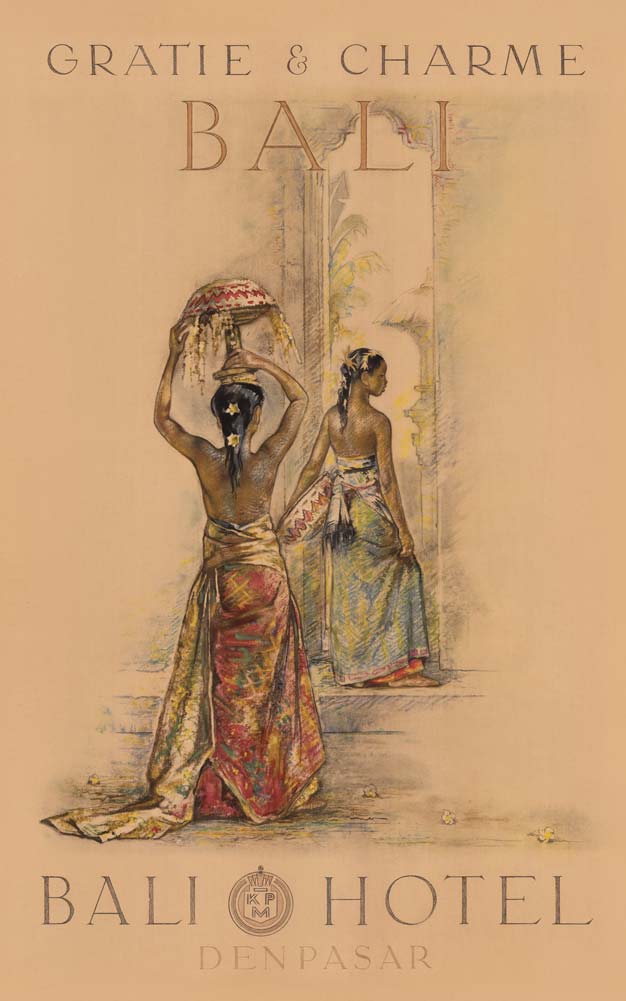

This isn’t new, according to Radit, who notes a fragmentation even in the very beginnings of tourism. It starts precisely 100 years ago, in 1924: “When Koninklijke Paketvaart-Maatschappij (Royal Packet Navigation Company) established a weekly steamship route between Bali, Batavia (Jakarta), Singapore, Semarang, Surabaya, and Makassar. KPM eventually opened the first international hotel in Denpasar, Bali, in 1927: the Bali Hotel,” writes the history buff. Many will recall the beautiful tourism posters drawn by the Dutch artist Willem G. Hofker advertising the island and the Bali Hotel (1947).

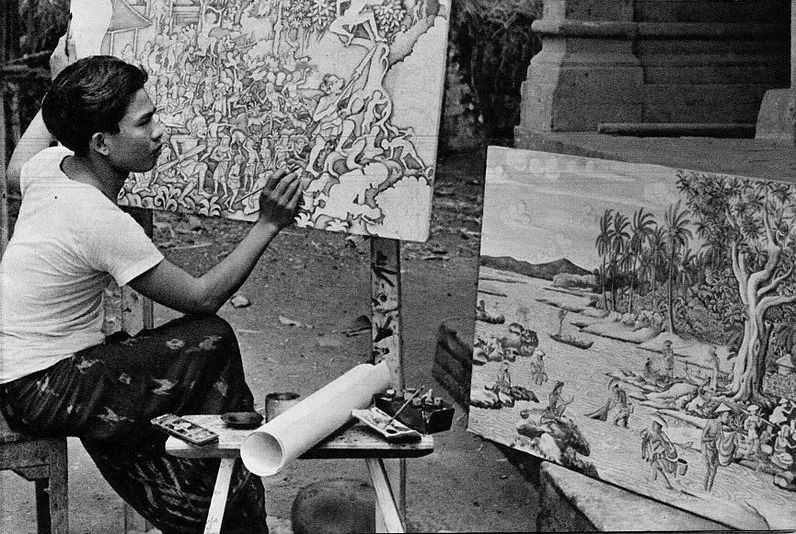

However, separate initiatives were happening in these early days: in Ubud, the royal family had begun inviting artists to take residency with them, seeing the arrival of German artist, Walter Spies and Dutch artist Rudolf Bonnet. This would result in the birth of the Pita Maha Art Group (1936) which was the driving force behind much of Bali’s ‘cultural exposé’ around the world.

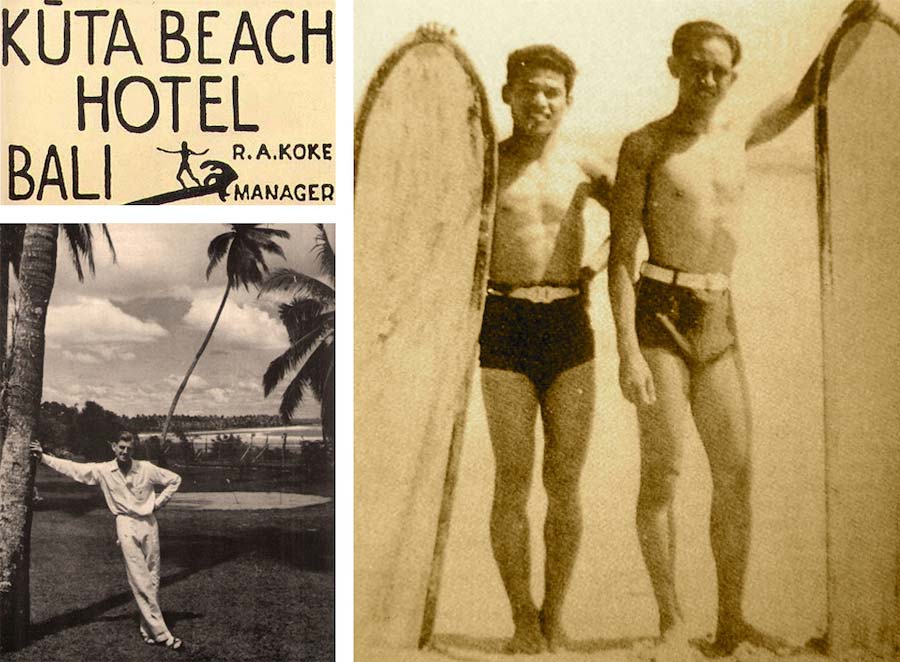

Also in 1936, quite independent of this, was the arrival of a young American couple. Bob and Louise Koke arguably pioneered the ‘beach and surf escape’ with the opening of the Kuta Beach Hotel Bali.

Right: Photos of Bob Koke’s Kuta in the 1930s (source: Smithsonian Archives)

“In my opinion, these two ‘styles’ of tourism have existed to this day,” comments Radit. On one side the exotic cultural enticements started by the Pita Maha and the promise of a paradise island and swaying palm trees that the Kokes experienced.

Due to the Second World War, these initial sparks of tourism were snuffed out before they could properly catch fire, but the word was now out about Bali. The next big development came after Indonesian independence when the national government made a concerted effort to make Bali an international destination. They built a behemoth, 10-storey hotel in Sanur which was to be the Bali Beach InterContinental Hotel (later the Bali Beach Hotel, The Grand Bali Beach, then Grand Inna Bali Beach).

Opening in 1966, its Miami-style structure drew some protest from local residents saying that the entire building was an insult to the island and its environment. Ironically, the uproar led to the establishment of new hotel guidelines in which the government itself stated no building must exceed 15m (the height of a coconut tree) and should adhere to local aesthetics. “This was spearheaded by prominent figures, including Wija Waworuntu of the Tandjung Sari,” adds Radit.

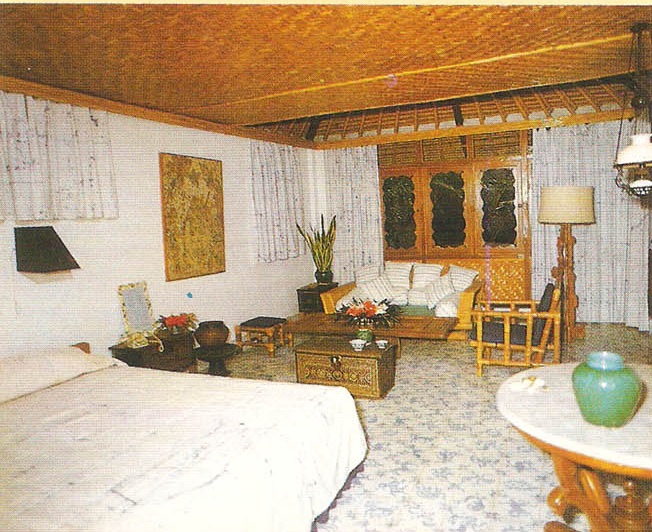

Wija and the Tandjung Sari Hotel are important catalysts in Bali’s development of a modern identity. Wija Waworuntu was a mixed Dutch-Indonesian, born in Holland but raised in West Java. A natural creative, Wija was a bamboo furniture producer by trade, but his interests expanded into art, antiques, architecture, Balinese culture and design. Tandjung Sari was not built as a hotel but as a home base for business trips from Jakarta, and slowly expanded with four small bungalows to accommodate visiting friends.

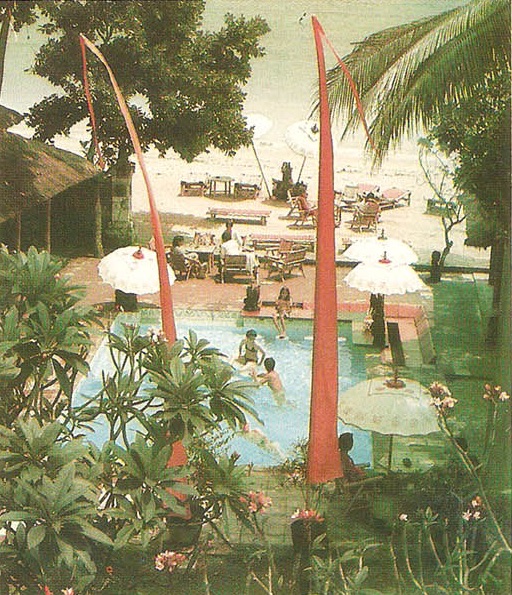

When it was constructed, back in 1962, it was the antithesis to the towering Bali Beach Hotel. Low-rise and low-key, built within the principles of traditional Balinese architecture, it was the epitome of understated luxury. Waworuntu’s artistic flair and penchant for good living filled it with life. This was the birth of Bali’s first boutique hotel.

Radit’s personal interest in design and architecture means that he has read this history through a particular lens, but it has helped to pinpoint a significant moment. This began with the arrival of the artist Donald Friend in 1962, who a few years later stayed at Tandjung Sari and became a partner of Wija. This would snowball into a renaissance of sorts that would help to define Bali’s new ‘face’ to the world.

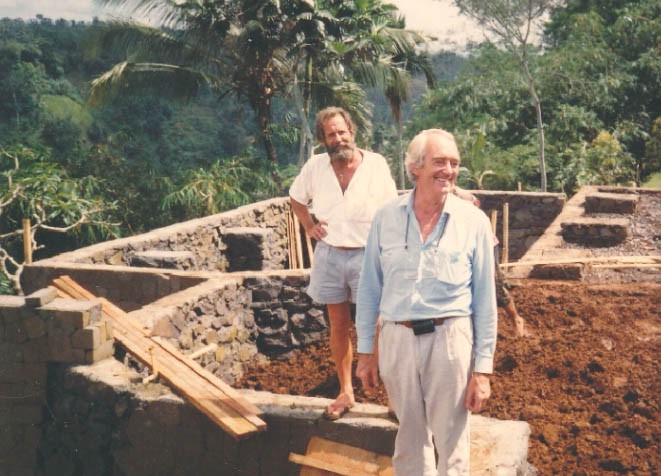

Wija and Donald developed Batujimbar, the iconic estate that sprawls along prime beachfront land of Sanur. Envisioned by Donald, the estate was designed by none other than renowned Sri Lankan architect, Geoffrey Bawa, father of ‘Tropical Modernism’. Inspired by Balinese traditional architecture, with raised brick pavilions entered through jutting steps, open balés with thatched roofs and open courtyard layouts, Villa Batujimbar was born. Through Bawa’s particular style, the vernacular architecture was subtly transformed for modern tastes.

This became the keystone in new Balinese hotel design. The Batujimbar estate housed influential Australian architects Peter Muller and Kerry Hill, as well as legendary hoteliers Adrian Zecha (Founder, AMAN), Ong Beng Seng (Founder, Four Seasons Resorts in Bali) and his wife Christina Ong (Como Hotels & Resorts).

This unlikely combination of powerhouses shaped Bali’s hotel landscape, with iconic hotels born out of this concentrated interaction between visionaries. The Bali Hyatt (Palmer & Turner – room & buildings; Hill, lobby & public facilities), The Oberoi (then Villa Kayu Aya, Muller), Amandari (Zecha and Muller), Four Seasons Resort Bali at Jimbaran Bay (Ground Kent Architects-architect; Jaya Ibrahim, interior refurbishment). A notable mention is of course Made Wijaya, aka Michael White, the famed landscape designer who brought life into many hotel developments.

The creation of these hotels in the 80s created what would eventually be considered ‘Bali-Style’, a new Balinese export of sorts that inspired a new tropical aesthetic and even lifestyle. It was a golden era, attracting the likes of David Bowie, Mick Jagger, Annie Lennox and Ringo Starr. They had found that balance between localism and contemporary comfort, a recipe that has contributed to many of these properties remaining timeless to this day.

Bottom: Designing the Amandari, Ubud. Courtesy of Peter Muller

“Designs were informed by an intellectual curiosity and genuine desire to create something that was appropriate for the surrounding environment. They were respecting the landscapes and using the local raw materials,” reflects Radit. “They were just learning, putting it all together. The buildings are a documentation of their journey in understanding what Bali is.”

Whilst these grass-roots style visions were being celebrated, the Indonesian Government had other ideas. In 1982 they created the Bali Tourism Development Corporation (BTDC) complex in Nusa Dua. Grand resorts manifested in this manicured complex and five-star resorts, commodious and luxurious with hundreds of rooms, became the island’s mainstream destinations. Due to building regulations set after the construction of the Bali Beach Hotel, the resorts adhered to lower-rise, Balinese-inspired designs, and intended to invoke a sense of local culture and atmosphere.

Nevertheless, the large-scale nature of BTDC changed the tourism landscape. Bali now needed high tourist volumes, rooms had to be filled, and this created a shift in the industry. Slowly a mass-tourism model crept in and has since seen the development of multiple tourist hubs over the last two decades, from Kuta to Canggu, and even over-tourism in areas like Ubud.

“I think we really lost control after the Bali bombs,” Radit muses. “We were so desperate to have tourists back that at that point we adopted an ‘anything goes’ philosophy.” This certainly parallels post-Covid Bali, which appears to display the most ravenous and all-consuming development in the island’s history.

We now find ourselves on an island of mixed signals. Not quite the ‘island of art and exotic culture’, as first portrayed by the Pita Maha; nor the surfer’s tropical escape of Bob Koke. Not that these should continue, but there seems to be no particular ‘style’ that defines the island’s identity appropriately and accurately. With changing demographics of foreign residents and big Indonesian investors, Bali has become a canvas upon which others paint their own visions — and often without the island’s best interest at heart. This ‘bring the outside in’ mentality is certainly in contrast to the perspective of the Sanur designers, who wanted to ‘bring the inside out’.

It may be too late to change what exists, but, much like the original ‘master plan’ made in the 70s, Bali must create a new set of principles that guide the island’s tourism industry to brighter futures. One that creates a clearer image of what the island is and stands for.

So, where do we go from here? Radit is inspired by the hotel group he currently works for, Aman, whose ethos is to ‘maintain locality’. “We need to have some self-respect for what we have to offer. At the end of the day, Bali’s backbone is its landscapes, people and culture,” he shares.

“I don’t like the idea of Bali being pigeon-holed. Culture doesn’t have to be trapped in the past; it evolves” says the visual communications graduate. He draws a parallel to Japan where even in a spectrum from rural traditional to hyper-modern there is an obvious and almost tangible ‘Japaneseness’. He quotes Indonesian designer Jaya Ibrahim, “I do not have to wear batik, sarong and a blangkon for people to know I am Javanese. They will know it from my spirit.”

The Potato Head Suites, previously called Katamama, is one example Radit shares of how we can approach Balinese heritage in a contemporary way. Though it may not appear obviously Balinese in form, it is a showcase and celebration of local artisanship. The entire building was constructed out of 1.8 million terracotta bricks, each hand-crafted by artisans in Darmasaba Village; in-room fabrics use local indigo-dyed ikat; and it featured a bar-meets-lab entirely dedicated to arak, the local alcohol. Other examples are certainly out there.

“What is quintessentially Bali? The kecak dance is not pure, it was made in the 1920s, though inspired by original choreography,” continues Radit. “Even the ‘Bali-style’ architecture is not exactly Balinese, it was made for contemporary tastes at the time. But these have the origins, essence and processes that respect Bali.”

Tourism today is seen as a commodity, and hospitality is often approached as such. But clearly this is having severe negative effects on the island, and also on the visitor experience. Is there a way in which we can improve all simultaneously? Radit doesn’t quite share a solution, but a philosophy that may help us get there:

“The original definition of hospitality comes from ‘being a host’. And that’s how I think we should think about Bali’s tourism, we are hosting people in our home – we provide what we, our house and our surroundings have to offer.” This mindset opens us to provide something uniquely and unashamedly ours. And yes, when we invite people into our home, don’t we always make sure the place is clean and tidy?

To stay in the loop on the publishing and updates on ‘Paras’ make sure to follow @parasparas_ or at parasparas.com | An exceptional ten-part blog series titled “A Quite Long History of Bali Hotel Architecture” by Radit is available at raditmahindro.medium.com