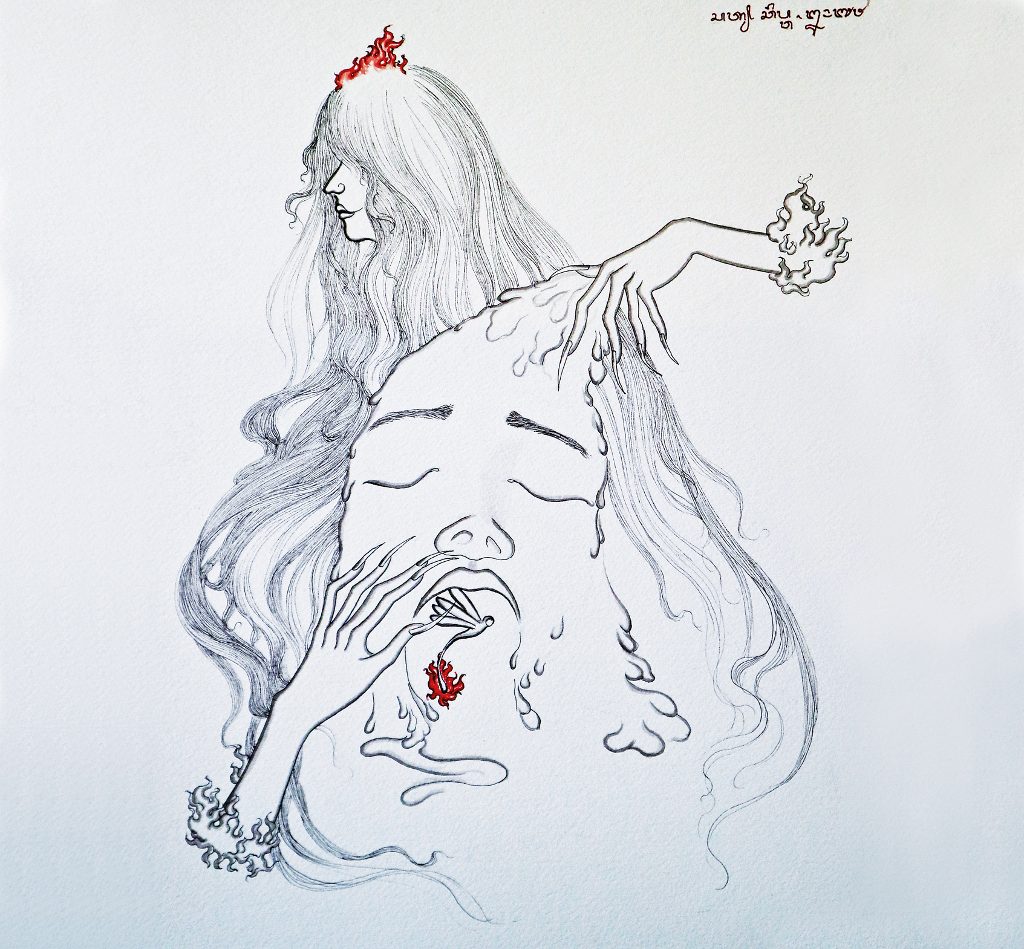

A story about Sekala and Niskala, the seen and unseen world or forces, that are believed to exist in Bali. Dr. Jean Couteau brings yet another one of his Balinese stories – sometimes myth, sometimes a mystery, but always meaningful:

These are the objective facts: Gobler was tired. It was night, and he wanted to get home before it was too late. The road past Punjungan was a pleasantly curvy one through the forest. It was a beautiful drive, he was comfortable inside his car, and he was glad to see that he would soon overtake and pass the slow truck ahead of him, thus speeding up his trip home a bit.

But just as he was about to pass the truck, a bike coming the other way surged into his path. It just missed him, but there was another bike right behind and it crashed squarely on the hood of his car. Gobler went blank.

When he came to, he sat there dazed for a few moments, staring out through his cracked windshield at the darkening sky, trying to remember what had happened. And then, to his horror, he noticed two bodies lying by the side of the road. A few hours later, one of these two passed away at the hospital.

Now, a few days later and in the comfort of his Denpasar house with his wife nearby, Gobler was explaining to me what had happened.

“Yes, it was my fault. I was on the wrong side of the road, but the youth could have avoided me,” he said. “The first one did. There was enough room. The second one could have avoided me, but, instead of swerving away he was sucked toward my car. So sad. He was only 16.”

“Sucked?” What did he mean? Before I could ask, Merni, his wife, explained: “There is no doubt. There was nothing the boy could do: he was melik – meaning “not really his own” in Balinese.

I started understanding. Gobler had had his accident, but it was not really his fault: what happened had to happen. There were niskala (or unseen) forces at work – at least according to Merni. Melik is what happens to people who have lost their inner balance; they can be manipulated by niskala (unseen) forces of any kind, divine or demonic.

From the time Gobler had called her, Merni knew it was melik that caused the accident. In fact, while Gobler was busy with the police the day before we met, she had already decided to consult someone who would tell her why this young fellow had rushed toward the car instead of avoiding it. She knew they would have to deal with the boy’s family and she wanted guidance, to “ask for words” (nunas baos) in effect.

She was indeed sure: her husband was not in the wrong – even if he had overtaken the truck at the wrong moment. He was a mere instrument of the niskala. And one does not play with niskala. The boy was dead, but his soul was still somewhere and it demanded attention to prevent more unfortunate things from happening.

So as soon as Gobler was released by the police, together they went to Kak Lingsir in Bangli. The old man had already helped them on a previous occasion, and he would “know”. When one came asking for his help, even with simple offerings and a few rupiah slipped underneath, he always had the knack to make those niskala forces “talk”. Indeed, as expected, with Gobler and Merni attentively listening in Kak Lingsir’s dim room, the dead body’s soul could eventually be heard speaking through the old man’s mouth, amid the shrieks and grumbles of the niskala world.

“He was bound to die in his youth, anyway,” the relieved Gobler was now seriously explaining to me. “He was cursed (kepastu) from the beginning. When he reincarnated, his soul left an unpaid debt contracted in “the field of sorrow” (meaning in hell, neraka). It had reincarnated too early, before being fully purified of all sins”

“This is why he was melik,” concurred Merni. So the boy had to go back to the field of sorrow to finish paying his debt.

“Yes,” Gobler added with a stern face, “I released him from his curse (nyupat); he has now paid his dues”.

Merni nodded approvingly.

What did all this mean? That the boy’s soul, if handled with proper rites, could now go its own way, enter the realm of the dead to eventually come back and reincarnate, this time without any curse hanging over it?

When Gobler and Merni explained the ordeal, in their comfortable Denpasar house, the dangers of all types – from the invisible (niskala) as well as the visible – or sekala – were obviously over.

But this had not been simple. There had been costs. The family had not sued. But Gobler had had to pay. There had been a sort of bargain, although not one motivated by money, of course. That would be too obvious, and could have disturbed the niskala world. But the ritual costs the boy’s family incurred had to be taken into consideration. The local police, no less wary than anyone about the unpredictability of the niskala, supported the arrangement.

The boy’s soul had then to be fetched by a balian (a traditional healer) from the spot of the accident. Otherwise it could run amok as an atma kesasar (an erring soul) with new evil consequences. Thus this ceremony, the ngulapin, enabled the body to be properly buried. Afterwards, as explained above, its soul could go on its way, to be cleansed in hell and of course reincarnate sooner or later when its time came.

When Gobler and Merni told me their story, they were not faking, or playing a game aiming to deny that Gobler was in the wrong. They believed in the melik, in the supat, in the intervention of the niskala forces that had caused the boy’s death.

In fact, their belief was reinforced by the fact that Gobler himself was not clear of all niskala woes. Shouldn’t he have already become the priest of the Segara Rupek temple? Had he made a mistake to postpone it to pursue his studies? It was no surprise that a little refrain was regularly singing in his mind: if he had this accident, was it because of his own karma? Was it to remind him that it was high time he be inducted as the mangku priest of the Segara Temple?

In his village some people were probably hearing a similar refrain. Highly troubling, isn’t it? And impossible to resist. So Gobler told me that he was now, at last, preparing for his mewinten induction ceremony. He had had his own ngulapin rite near the accident spot, to restore order to his soul. And he was cleansing himself (melukat) in visits to holy temples around the island.

Not all Balinese react like Gobler and Merni in a situation of accidental salah pati (wrong kind of death) like above, but the majority do react similarly in similar circumstances. The other ones will have doubts, the doubts of modernity.

As for me, I am not like Gobler. I am a Westerner. So if I have an accident, I will not believe in the depth of my psyche that this accident was caused by mysterious forces out there. I would probably enter into depression, unlike Gobler, who is now ceremonially restoring the proper balance of things. From a Balinese perspective, it is a happy ending : The boy’s soul has gone back to where it belongs, and Gobler is becoming a temple priest.

So much for the notion of personal responsibility. To be responsible in Bali is to fulfil one’s duties towards the niskala at least as much as toward the sekala (visible) world. Fascinating, wouldn’t you say?