Balinese are nowadays basically like you and me. So when they kiss, it is on the mouth. Yet, if you pay attention, or are in the middle of a kiss, you may notice a difference. All of a sudden, and without understanding his/her logic, you may see your Balinese partner take himself/herself off your mouth, and start rubbing your nose while sniffing. The nose is indeed an ill-understood focus of Balinese-style eroticism, if mainly at its early stage.

But there is a reason beyond the vagaries of Balinese Eros: tradition, and within tradition, hygiene. In old times, there was no toothbrush and toothpaste. And the mouth was not the most enticing part of the body. Like other bodily orifices, it stank. People’s favourite way to cope with it was to chew betel-nut, but the result did not allow satisfactory kissing either: it cleansed the mouth, but damaged the teeth. No surprise that many people would choose to brush their teeth using the extremity of a small branch of siwak. Others used their fingers to brush their teeth with ash or brick powder.

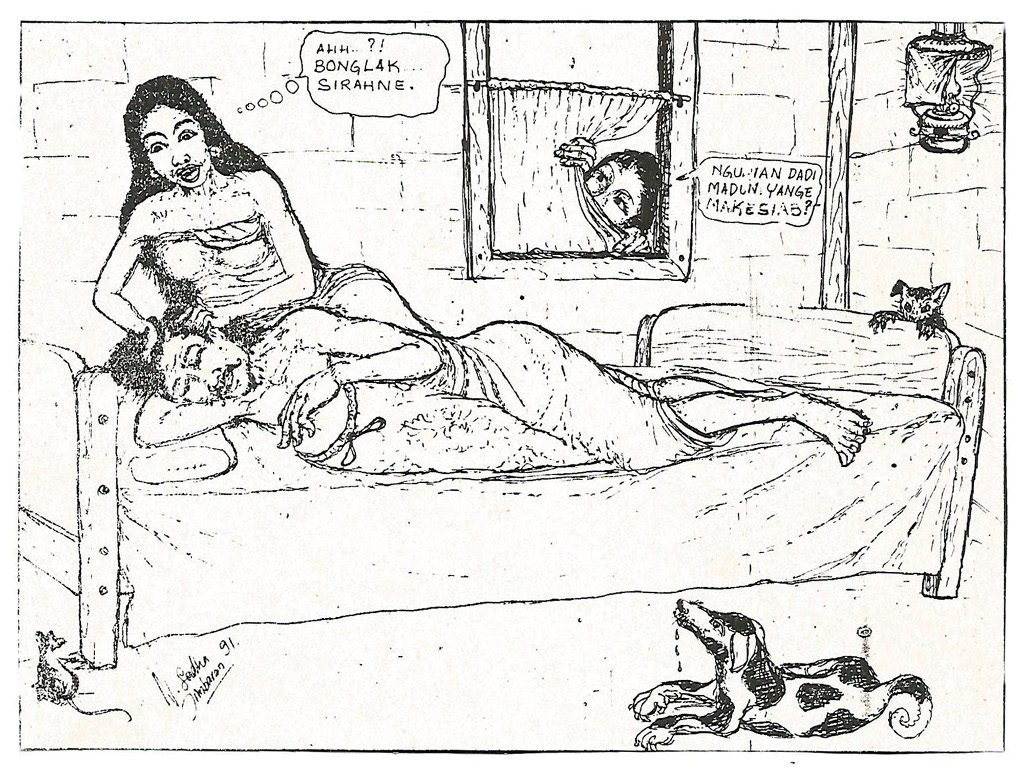

If teeth brushing was a problem in the past, so was looking after one’s hair. The problem was not so much with shampoo: one could use magnolia leaves for the purpose. It was getting rid of lice. Especially for girls. Scratching one’s head lacks elegance indeed in the presence of a beau. Yet, delousing also enabled Balinese women to meet with one another for a talk. And they enjoyed it. It was usually in the afternoon, after work, when the sun was not so hot anymore. They also needed a quiet and cool place, if possible one with a flight of steps, so as to perform the task with maximum ease. For sure, the place chosen could not be a temple or a shrine, but it could be almost anywhere else: a granary, a pavilion, or even some place in the fields.

Delousing was the perfect moment to catch up on the latest gossip: “Hey, Putu,” one would say, while smashing a louse between her nails, “did you hear the story about Men Gabler? She can turn into a leyak witch, they say; she has managed to make Pan Gede gravely ill; avoid her company”. And thus they would engage themselves for hours, changing turns, sometimes in a file of three or even four, each on one step, with only the lowest one idle, although not for gossiping. When not gossiping, or after it, women would often feel so comfortable that they would fall asleep, sure that all their lice were hunted down and smashed between the nails.

Yet, delousing by hand is not very efficient. This is why the Balinese also use a special wooden comb with narrow interstices between its wooden teeth. The lice can easily be trapped between the teeth of the comb and then killed. But it is a luxury of sorts, and few people owned such a comb, though, they would pass it from hand to hand. Another aspect of delousing was to provide the perfect ingredient for medicine against jaundice and hepatitis. The insects would be caught alive, inserted in the flesh of a “golden” banana (pisang mas) and then swallowed. Taken three times a day, a cure is guaranteed, people say, and at a much cheaper price than a doctor’s medicine.

Yet, delousing is disappearing, and so is traditional bathing. Today, piping has been installed in many villages and most people have direct access to tap water. So they bathe at home. But it is a very recent phenomenon. If you travel through the island, you can still see village women with earthen water jars on their heads, heading for a public bath. One of many types: a pancoran (a waterspout pouring out above a rock), a tukad (river), a tibu (deep pool in a stream), an empelan (open tank filled with water from a pancoran), a telabah (ditch) and last but not least a kelebutan (spring). Usually, men and boys do not carry anything, except for a bar of soap and a towel draped around the neck. You may protest about such a “gender division” of labor, but it is a fact.

By the time you arrive at the site, you might be taken aback at the way they bathe. First, washing is not to them less a burden than a social event. Some men and women walk up to a mile or more just to go to a public bath. Once there, bathing is made to last, sometimes a few hours. And finally, they bathe nude. Let us not forget that it is pictures of Balinese women at the baths, published in a book 100 years ago, that made Bali famous the world over. But for them, nude bathing among both sexes is deemed normal, men upstream, women downstream. Completely naked, they wash themselves from head to toe without betraying the slightest embarrassment. There might be jokes, but relatively few lewd ones. It is not the place for men to be rude with women. Everybody seems to focus only on one’s own body, oblivious to all others. Most importantly, when people go to bathe publicly, it is to meet people and talk. Preferably to gossip.

This gossip can be convivial, but also sarcastic. Because Balinese can indeed be very blunt when among themselves. When a bather sees one of his rivals arriving, he may welcome him with a ‘joke’ such as this: “Nyen ene ? bonne jelek sajan,” (who is this, he stinks) to which the latter will probably reply, “Yen ci ngadek bo jelek , cunguh ci-e ane ngebo” (If you smell a bad odor, then it is your nose that is stinky).

The exchange is nicer when bathing is a pretext for courting. “Tumben dadi mara tepuk,” will say the boy to a girl as he tries to approach, (How nice to meet you here). To which the girl may reply coyly: “Icang ngoyong dogen jumah” (I just stay at home). “Beh! Dadi bungan natah. Sing dadi pesu !,” the boy will probably comment (Ah! you are a home-kept flower and are not allowed to go anywhere). Those are standardised sentences. If interested, the girl may reply with another set of ready-made words: “Sing ja keto. Sing taen ada galah pesu” (It is not like that, it is just that I just don’t have the opportunity to go out). The boy will then try his chance for good: “Apa dadi cang nganggur kemo.” (May I visit you). Many love stories actually began at bathing spots.

All the habits above have disappeared, or are quickly disappearing: gossiping is replaced by sosmed (Social Media); people don’t want to eat lice as medicine and, when courting a women, you still start by bathing with her, but the end in view is different. These are modern times, lousy times.