BASABali – a registered foundation in Indonesia and non-profit in USA – are a collective of linguists, anthropologists, students and communicators who are driven by the same mission: to ensure the continuation of the Balinese language. Alissa J. Stern, Founder of BASAbali; and Ni Nyoman Clara Listya Dewi, Head of Communications for BASAbali and a National Geographic Young Explorer, share directly how BASAbali has developed, and the birth of their unique digital platform.

We set out to help invigorate a language spoken on one of Indonesia’s islands by engaging the local community in developing an online dictionary using the language. The community’s input did more than provide data: it broadened our approach so that the community is now harnessing the power of the dictionary’s digital platform for active discussion of key civic issues, while also increasing usage of the language.

Our initial goal as a nonprofit organisation back in 2011 was to bring the language of Bali into the modern digital world in order to save it from slow, but inexorable, extinction, a fate in store for most local languages in the internet era’s absent radical intervention. We thought that if we could engage the community to contribute simple Balinese language video selfies to a digital dictionary, people would see and hear Balinese being used online, which would normalise its use on the internet.

We were intrigued with the way that the decade-old (at the time) Wikipedia was being developed by the public, and thought that we might be able to use a wiki – an online platform that can be populated and edited by multiple users – to include the community as co-producers in the development of a free public resource.

Wikipedia and its dictionary offshoot, Wikitionary, weren’t available in Balinese at the time. But even if they were, we wanted something that looked and felt more Balinese and was organised in a way that made sense to the local community, not just translated and transported from the U.S. We wanted a platform that was as easy as possible for the public to add multimedia resources without needing a whole lot of instruction; we wanted the platform to be as inclusive as possible, especially for women and girls and marginalised voices; and, we wanted a platform that could handle the idiosyncrasies of the traditionally oral Balinese language.

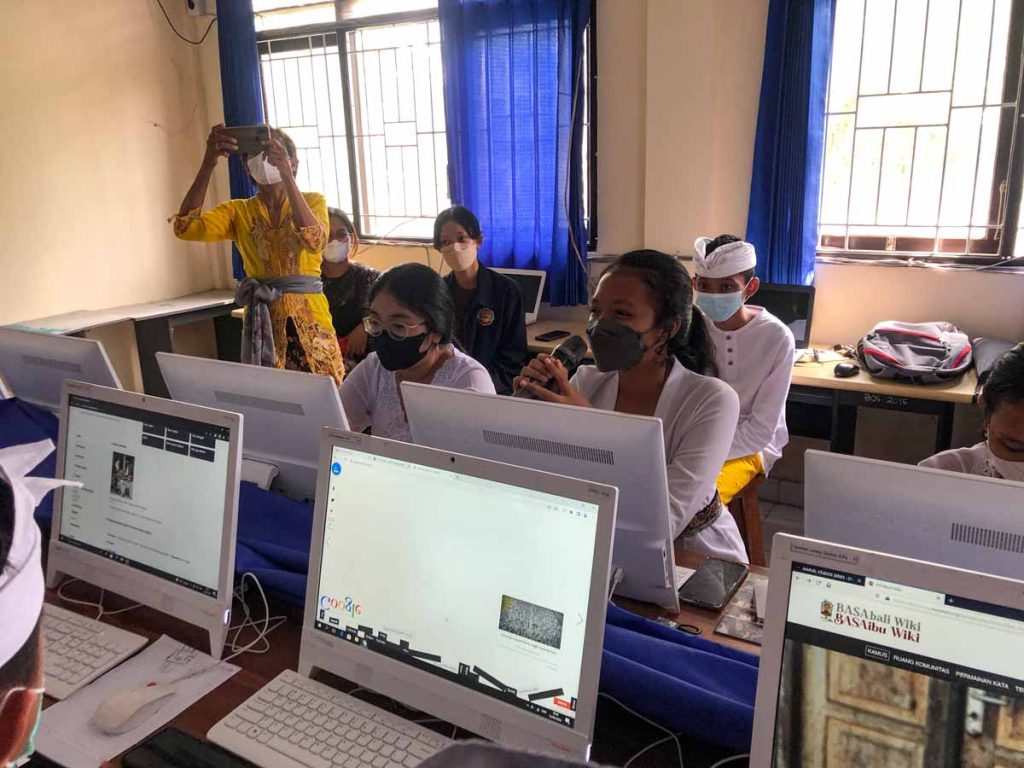

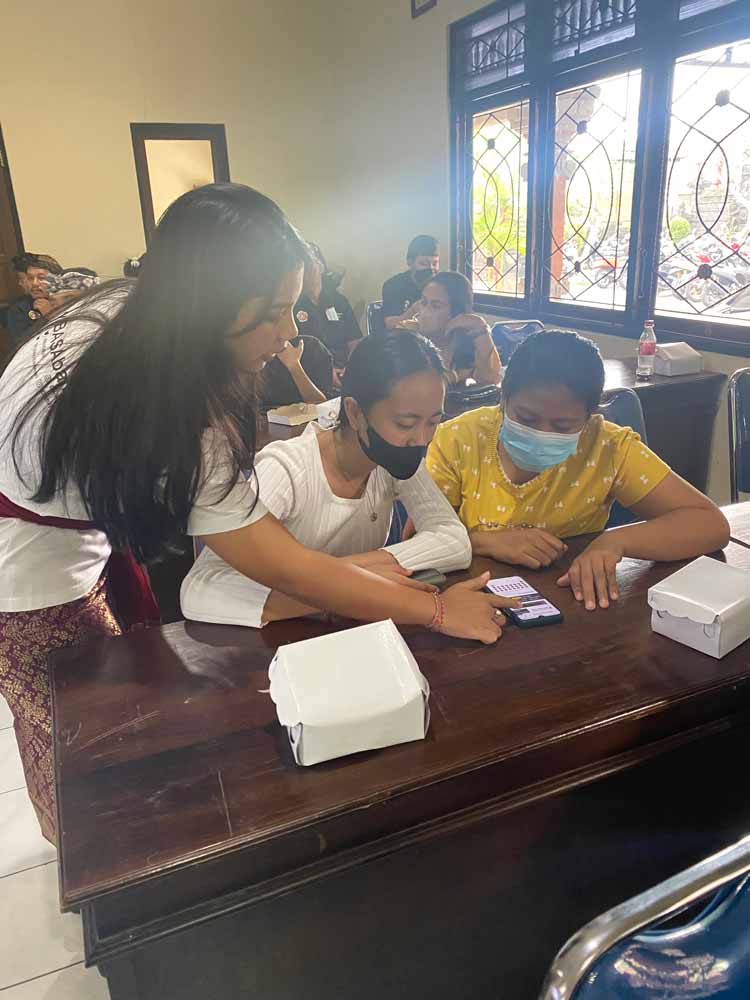

We sent young people into villages throughout Bali and asked them to use their cellphones to help people create simple videos giving directions or describing how they spend their day using the Balinese language. Hundreds of people uploaded their videos to the dictionary or handed us thumb drives if they didn’t have sufficient bandwidth. Within three years, we had built a digital dictionary with the community.

But to our surprise, people also gave us suggestions about what else we could do for the community with wiki power. “What about an artists’ directory to help local painters and writers get known outside of their local village?” “What about a people’s history?” “What about something on the evolution of Balinese ceremonies”?

So, we “listened to our market”, as a private entrepreneur would say, and pivoted, expanding the platform from dictionary to dictionary-plus-encyclopaedia. Over a period of few years, we grew to about a million users with people contributing data about their lives, rituals they were participating in and places they lived.

In 2020, after the pandemic hit, we were offered a small grant to use the wiki to assess how the Balinese were faring under Covid. That put us in a new position where our wiki had to do more than engage people around data. Now the digital platform also had to elicit their opinions. We wondered: Would people respond? Would the platform get out of control?

We had used ‘wikithon’ competitions to inspire contributions to the dictionary, so we decided to use a similar digital competition to challenge people to write about how they were doing under the pandemic. We explained that it wasn’t a writing competition but rather an opportunity to talk publicly about Covid challenges, strategies and resilience. Winners would be chosen by a jury and by public vote. Responses poured in.

We realised that along with talking about how they were experiencing the pandemic, people also talked about a wide range of civic issues: public health, infrastructure, and what help was needed from the government. We were stunned not because of the subject matter or the civil tone but because Indonesians were publicly discussing civic issues at all. And they were doing so without the government reacting.

A 2001 policy on regional autonomy tried to push governance down from the central government to the regions and at the same time open policymaking up to public input. Civil society has since been working toward effectively participating in civic issues but many still lack capacity and experience and many public participation processes still need to be clarified.

As with groups, individuals in Indonesia have not tended to publicly participate in civic issues even though the internet offers an avenue to do so. A 2018 study by Pew Research found that only 18% of Indonesians age 18-30 have voiced opinions online and 54% said that they would never do so under any circumstances. Yet members of the community were clearly using the wiki to discuss the economy, education, transportation, public health, and social mobility, all the issues one would expect a community to care about and want to have a voice in.

We began to understand that the community was using the wiki to do more than speak Balinese in the modern digital world: it was bringing the participatory nature of Desa Adat, Bali’s traditional village government, into Indonesia’s modern official form of government, which for years did not have a public participation culture.

At the same time, the capacity of the official government at the provincial level to make policies was beginning to catch up with authority that had been formally delegated to it almost 20 years earlier. This meant that, at least in Bali, the formal government was interested in community input and welcomed the wiki. The government and civil society increasingly offered suggestions for how to tweak the platform to make it even more useful to the community. We realised that rather than developing a digital platform to strengthen the local language, we were on a journey with the community to co-produce a local language digital platform to service the community’s evolving needs.

In 2021, major funding from a Swiss-based foundation gave us the resources to restructure the wiki so that it primarily encouraged people to speak out about civic issues instead of primarily being a dictionary with public participation capacity. The wiki is now organised in a highly structured and contextualised way according to community-defined sections. The sections are hyperlinked to one another and with the dictionary so that an entry about a particular village might have an elder’s account of the village’s history, details about the meaning of the village’s name, and a debate among millennials about what the village needs to succeed in the post-Covid world.

The support from the official government in Bali continues to deepen as the wiki gains more traction among the public. With the blessing of the Governor of Bali, the heads of government agencies urge people to speak up about civic issues on the wiki, and they are using the local Balinese language to do so.

Of the nearly 3 million people who have used the wiki, about 90% come from the 4 million people of Bali. In addition to going to scale in Bali, the foundation is supporting us to replicate our approach. We chose to replicate in South Sulawesi, Indonesia, a part of Indonesia with a very different socio-linguistic and economic culture from Bali. We have lots of questions as we go forward: Can this process be replicated? Is the civility on the platform due to the community’s culture, the structure of the wiki, the relatively small size or newness of the platform, or some combination of those factors? Is it essential that the host of the wiki is an NGO (compared with the government or a for-profit company)?

As we learn more about how communities can make the most of digital platforms for their own benefit, it is clear that, at the very least, the old adage about teaching a person to fish instead of giving them a fish holds true in the digital world. Translating Western platforms into Balinese (or even the national language, Indonesian) allows a local community to connect with and benefit from the world’s dominant cultures. But empowering the community to have the understanding, knowledge, and capacity to shape their own digital platforms to satisfy their needs is a far more engaging and sustainable path.

For more details on BASAbali and their Wiki, visit: basabali.org