Indonesia is home to one of the most fantastic trees in the world, the banyan tree, locally known as waringin, a kind of ficus. Apart from its size and surface, the most extraordinary aspect of the banyan is its resilience. When its vines touch the ground, they grow into new roots and trunks, spreading out in a tormented encounter of trunks and leaves. The banyan has become a favourite symbol of Indonesian political lore. On account of its multitudinous roots growing into a single trunk, it symbolises the unity of the Indonesian nation. As a shady and cool shelter, it also symbolises the protection of the state.

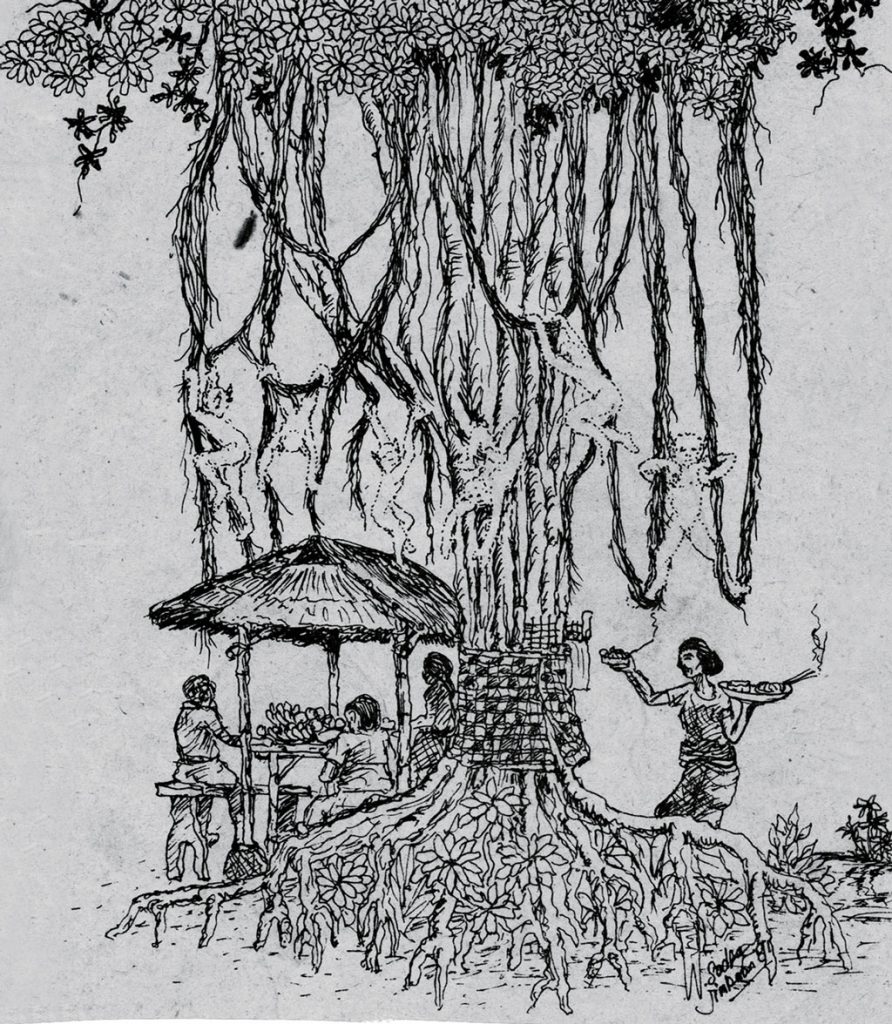

In Bali, keen-eyed visitors will no doubt notice the cloth wrapped around its lower trunk as well, sometimes, as the altars scattered among its branches. What does it mean? Why do banyans warrant such attention?

Banyans can indeed grow naturally, but most of them are planted for religious purposes in the vicinity of the main village temples, in particular near the temple of the dead, thus in the lowest part of any village. These banyans are the custodians of powerful gods “installed” there after the planting of the tree, through a pangurip-urip (bringing to life) ceremony.

In some villages, I was told, the tree has a female “dweller”. But in other places it is said to host no other than the fanged monster Jero Gede Mecaling and his mate, Jero Nyoman. The checkered black and white cloth around the trunk account for the famous deity, while the white and yellow for his mate. Jero Gede Mecaling is the principal cause of grubug, or diseases that used to sweep through Bali at the end of the dry season . But Jero Nyoman, the monster’s mate, is no less dangerous. She is said to hold sway over the gamangs, human-like monsters that make their dwelling in remote trees and bushes. Since they look human, in spite of a harelip and deformed feet, these gamangs like to goad humans into their realm beyond the trees. Stories abound of seduced men and especially women who have children by these lovers from the trees. It is used to explain the weird behaviour of some children.

There are ways indeed to avoid both the trouble and the scare: that is to propitiate or placate the banyan dwellers. Here lies the function of the altars and small temple found near the trees. The higher shrine is addressed to the gods, while the lower one for the gamangs, although there might be additional shrines for visiting gods and for some unknown deity who asked for attention in a recent temple trance. Lest a mishap happens, the local people are indeed wary not to forget any of the tree residents, known and unknown, including of course the demonic bhuta at the ground level.

The rites above can be construed as corresponding to the animistic side of Balinese culture. There is also a more noble, and more “Hindu” interpretation. The banyan is construed symbolising the junction between the chthonian (earthly) world, the bhurloka world of Hindu lore, where reside the bhuta, and the upper world where reside the heavenly forces, the swahloka, passing through the world of humans, the bhwahloka.

Therefore it binds and at once separates the tangible sekala world and the intangible niskala world. Going back to the pre-Hindu indigenous tradition, this junction role might well account for the role played by the banyan in the post-cremation ceremony called “ngangget don bingin” (the collection of the banyan leaves).

It takes place as part of the nyekah post-cremation ceremony, a few weeks after the corpse has been burned and its ashes dispersed into the sea. The purpose of the nyekah ceremony is to send the soul ‘back home’, to the ‘Old Country’ of the origin, above the mountains. For this ceremony, effigies are needed, which are made from banyan leaves. Using a long pole, the leaves are made to fall on a spread-out white sheet. If a leaf fall on its ‘back’, it must be used for a woman’s effigy; if it falls on its ‘belly’, it is for a man’s effigy. The leaves are then sewed together into a sekah effigy, male or female according to the need. This effigy will then be symbolically ‘brought to life’, thus reawakening the soul of the dead, meaning that the cremation has not fully eradicated all signs of life. In the following nyekah ceremony, the effigy will be burned in a simile cremation, complete with a mini cremation tower, and its ashes dispersed into the sea. At the end of the rites, the soul will have become a deified ancestor (dewahyang) residing above the mountain, and also ritually seated in the ancestral family shrine, where its descendants will address it through their daily prayers.

Yet, the leaves of the banyan do have another function. They are also used to make an offering presented to the Goddess of knowledge Saraswati on the last day of 210 day Pawukon calendar. The resilience of the rites held around the banyan tree clearly show that Balinese are much more than simply Hindu. The envelope may be Hindu, but to this day the content remains indigenous, with dominance of the cult of ancestors and of the forces of nature.