It seems as if every Balinese has artistic blood running through their veins, expressed through painting, sculpting or performance. Whether its its origins are nature or nurture – likely the latter – it has resulted in a society that thrives within the creative realm.

Yet, art is forever evolving. Even on an island where tradition reigns and religion with its derivate culture determines all, artistic expression evolves with the times. This is apparent in Bali’s newest generation of visual artists; souls rooted in heritage, minds moulded in modernity. Their art, therefore, is representative of this dichotomic relationship, which both connects Bali with and communicates Bali to the global art world. However, it’s not so simple. Whether born into an artistic family or not, the island’s local art industry still has barriers that must be overcome by independent artists and the path to recognition is far from clear.

Batuan’s New Hope

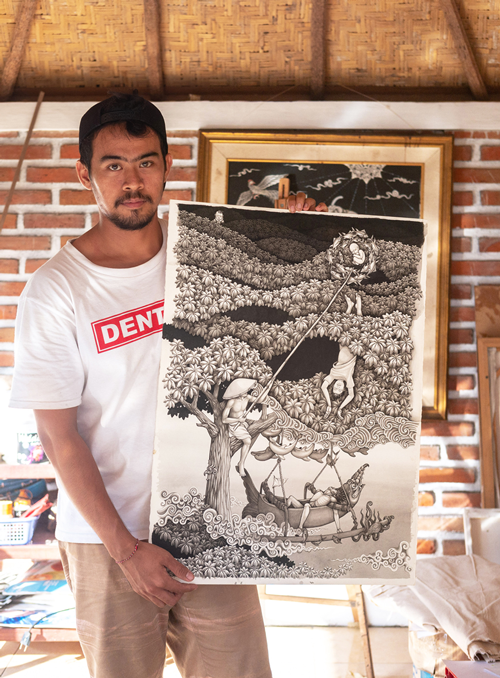

Wayan Budiarta comes from a long line of Batuan painters, his grandfather was one of the early generations, and his father, I Made Sujendra, is a well-known name in the Bali art scene and continues to paint. The Batuan artistic style has been this village’s legacy since its founding in the mid-1930’s, putting the area on the cultural tourist trail.

This school of painting developed around the same time as the Ubud and Sanur schools, when Balinese creatives took inspiration from foreign artists, changing the course of Balinese art forever. Each area took a distinctive style; Bruce Granquist, in his vibrant encyclopaedia of Batuan paintings, ‘Inventing Art’, described the style as “remarkably dense, with deeply saturated tones. The images are often dark and sometimes macabre… The forms in the paintings swirl and intertwine… they create labyrinths of pulsating light that leave very little place for the mind or eye to rest.”

Despite its historical significance, the Batuan school now faces an existential crisis, in fact many of the original art schools do. 26 year old Wayan Budiarta, Sujendra’s son, is one of four young painters that now carry the weight of this legacy on their shoulders.

“I don’t feel burdened by it,” says the third generation painter. “I paint because I genuinely enjoy it. I am simply an artist who happens to be in the Batuan style,” he continues, relieving himself of that pressure which he feels might stifle the purity of his expression.

Very few of the young talented painters in Batuan are forced to continue the village’s legacy, though efforts are made to realise potential. A collective of Batuan painters, his father included, run mentorships on the weekend, teaching techniques and history that will hopefully see the style preserved for future generations.

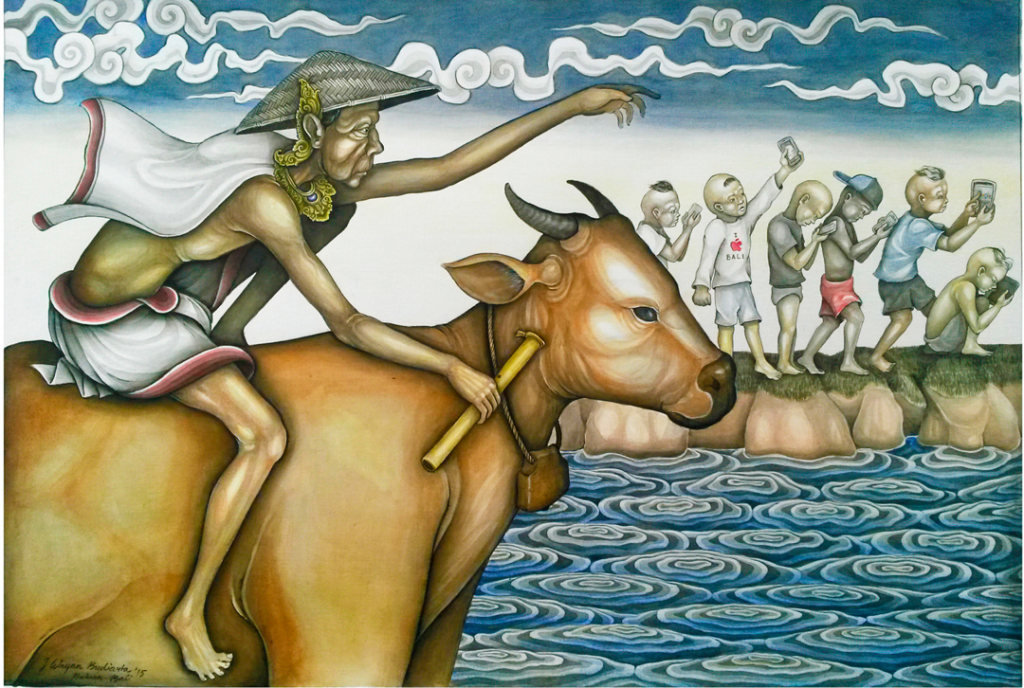

Wayan’s art features aspects that are distinctively Batuan; they are dense and busy, featuring multiple layers; each shape clearly outlined (nyawi); and they feature the identifying gradations of dark to light, ucukand mayunan.

But Wayan presents an updated version of his village’s legacy. When it comes to colour, he injects this traditional style with contemporary exuberance. Soft and deeply saturated tones, or the traditional black-and-white, are given the Midas touch of an almost pop-like vivacity.

However, it is really the subject and theme of his work that brings this school into the 21st century. “I paint what I see, what I feel and also some social commentary,” saysWayan. Batuan paintings often showcase depictions of hectic daily life, from ceremonies, farming or hunting, and mythology also has a place. The protege does this too, but introduces modern elements that act as sharp juxtapositions.

His 2016 piece, ‘Versus’ (used as the cover of our August 2020 Issue) depicts Hindu folklore heroes playing tug-o-war against modern day heroes such as Superman and Batman in front of a cheering crowd of babies. A commentary on the balance of tradition and modernity that the youth must struggle with. Another showcases a famous mythological scene of the Cosmic Turtle (BedawangNala) being constricted by a dragon, but he has replaced the turtle with a giant rubber duck.

“It’s just fun – a parody,” admits the painter. “Not all of my work started with meaning, I just came up with a fun idea and wanted to paint it.” A lot of his work depicts Balinese elements, but to that Wayan says, “yes well that is everyday life to me. That is not ‘Balinese culture’, but just what I see on a day-to-day basis.”

Art is all around Wayan; in his blood, in his village and in his culture. To him, art and being Balinese are intertwined, sharing that he and his father often paint the ceremonial prayer cloths (rerajahan) used by local priests. Yet, he manifests these modern-traditional juxtapositions on canvas. It seems clear that he himself is the product of the very same dichotic circumstance.

Despite his Batuan background and unique, modern take on the style, Wayan has not pursued being an artist full-time. A solo exhibition held in TiTian Art Space, 2017, was a success, yet this modest creator lacks the confidence. He says he doesn’t really know the market, nor does he have the capacity to mingle and network with art industry types. He knows there is opportunity out there for those who go looking for it, but he doesn’t see the path clearly. His goal for now is simply to paint more and prove to himself that he really is an artist.

The Punk Rocker of Art

Then we have Kuncir. This Tabanan native – real name Sathya Wiku Narabudhi – is the first artist of his family. Though, his family has always been in the arts, through dance and gamelan. “All Balinese are artists in some way”, says Kuncir, as rock music plays in the background and he pours a glass of arak. “It’s an expectation, through our culture, our religion.” Still, Penebel village from whence he hails has no art legacy and he never formally studied fine arts or painting. Instead he studied graphic design at InstitutSeni Indonesia (Indonesian Institute of Art) Denpasar, thinking this was would be a more practical, career-savvy pursuit.

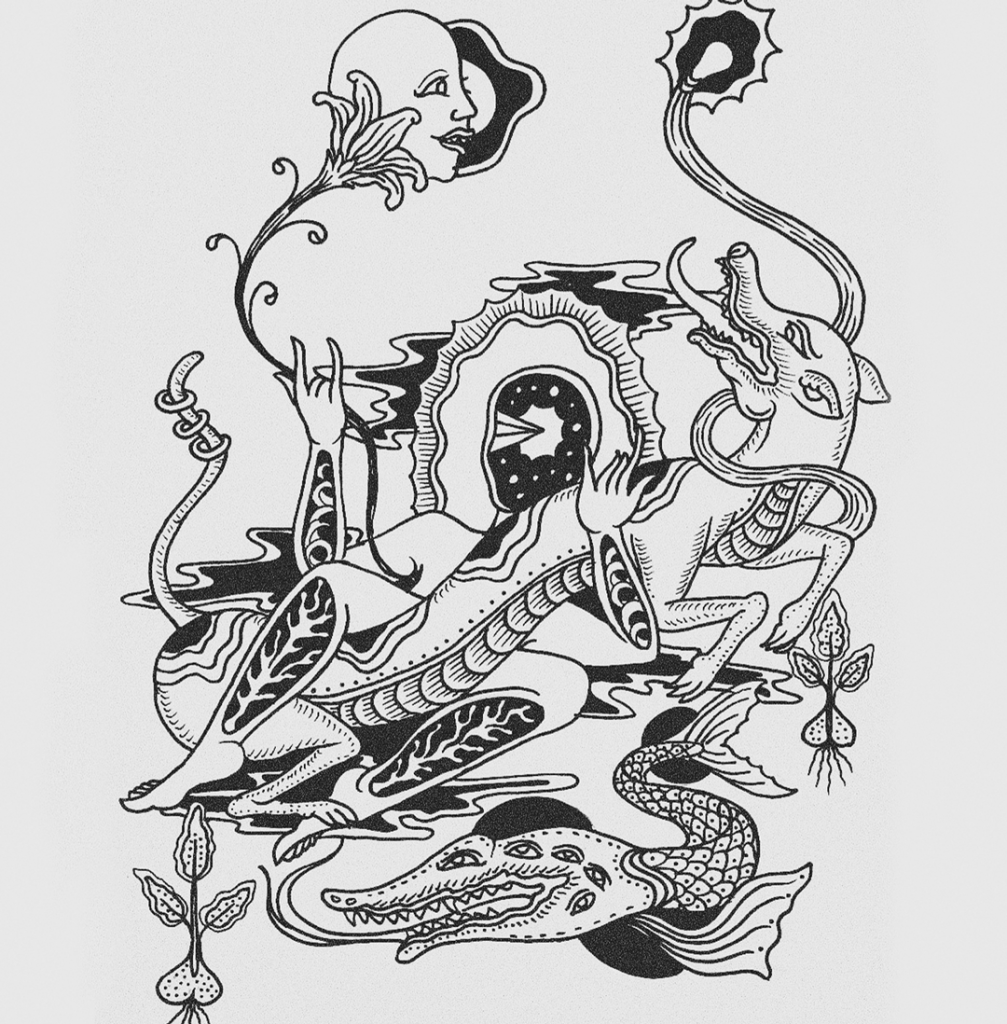

Without academic background in art, Kuncir is unsure of what category his art falls into. He paints on canvas, but a lot of his more popular work is Chinese ink on paper.

The style is akin to the great I Gusti Lempad, whom Kuncir called – jokingly – an artistic nabi, or prophet. The style is similar to the Balinese Hindu rerajahan, ceremonial prayer cloths used by priests, imbued with powers from mantras. These drawings – often featuring menacing mythological figures, geometrical symbols and aksara wording – are done in clean lines of black, with white spaces left blank surrounding the subject.

Kuncir’s own drawings are often surreal, with disfigured humans, creatures and shapes that meld and interact with one another. He says that some of the inspiration for the unusual imagery came from lontar manuscripts – his father is a pemangku (priest), thus Kuncir had a lot of exposure to this.

Style aside, it is the subject of his works that differentiates him from his predecessors. He refers to them as his curhatan, or his venting of frustrations, be them personal or societal. Whilst previous Balinese ink painters used the medium to present daily life, folklore and mythology, Kuncir has used it for expression.

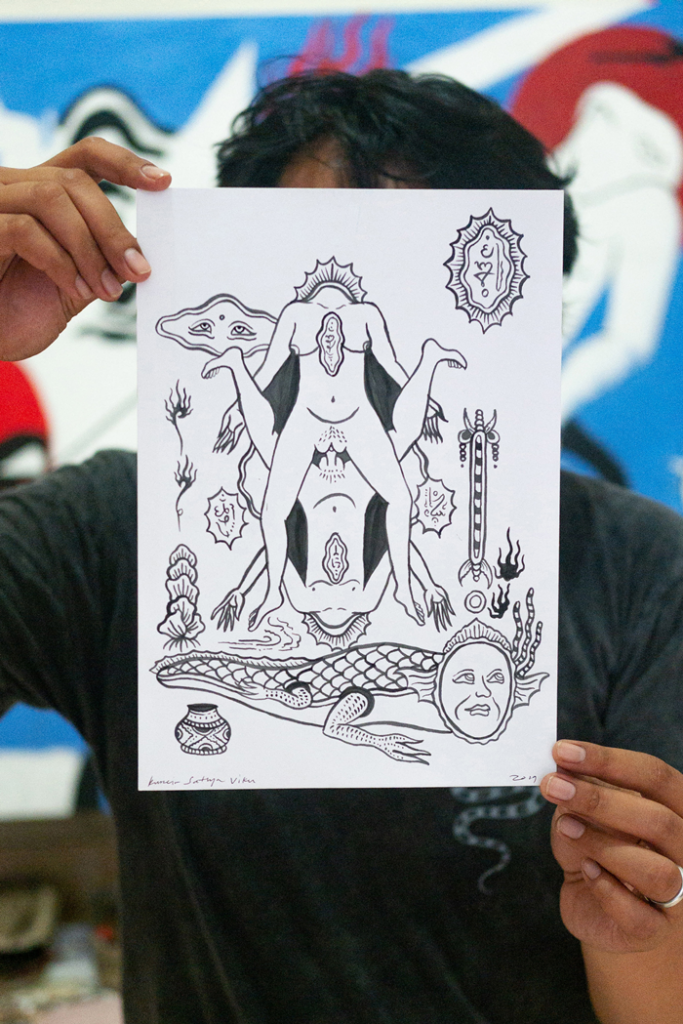

Standing behind Kuncir, a half-finished painting illustrates a figure in a state of paralytic confusion, a state in which he feels many are in due to Covid-19. He shows other pieces that depict themes of sexual frustration (his own), struggles against the justice system, self actualisation and other themes.

“Art is an escape from reality”, says the pondering artist. “It has always been calming for me when I’m stressed or anxious. But it’s also a safe space to discuss taboos, say what you want, challenge authority.”

In 2017, he held a solo exhibition at Deus Ex Machina called ‘Spiritual Sh*t’, in which his art displayed the grievances he had for his own culture.

“Bali has always been branded by the tourist industry… ‘paradise’!” Asserts Kuncir, concerned about the motivation for cultural preservation. “Our dances are entertainment for the gods; human enjoyment of the dance is just a side effect. But, so much of it is for show nowadays; who is all of it really for? Us, the gods or for the rest of the world to see?”

Through his art, Kuncir presents a perspective of the Balinese youth. That like the rest of the world, they have regular struggles, undefined by the often externally-perceived ‘exoticism’ of their way of life. Whilst the medium and style in which he expresses it are rooted in his culture, the stories he tells are both global and personal.

With little understanding of fine art or the history of art, he feels as if he doesn’t quite fit in with the formal art world.

“I think my art, like some of my friends’ art too, is like punk music. It’s taboo, it’s rough. The artists who make it into the galleries are the jazz musicians,” he confides. “Maybe I’ll have to make some kind of punk-jazz fusion to get there”, he says jokingly, unwilling to abandon that ‘punk’ identity.

The Future of the Next Generation

It’s clear that both artists are both rooted in and influenced by their own culture, surroundings and daily influences. Their works presenting themes, subjects and styles that pay homage to their Balinese background. However, what makes them unique in the global art world also limits them under the banner of Balinese art, when in fact these present-day artists convey messages more akin to contemporary art.

To use what WayanBudiarta said, “I am simply an artist who happens to be in the Batuan style,” they both are simply artists that happen to be from Bali. Kuncir and Wayan present the future of Balinese art, which introduces modern subjects that are relatable to a younger but also more global audience. The intersection of old and new in which they both reside has the potential to connect Balinese art to the wider world, whilst simultaneously presenting a newer ‘brand’ of Bali to the world, one defined from the everyday Balinese themselves.

Follow these artists on Instagram

WayanBudiarta: instagram.com/budiartawayan1

Kuncir: instagram.com/kuncirsv