Living their day-to-day, the Balinese follow a set of rules and routines inherited from their ancestors, recorded on palm-leaf manuscripts. From plant-care to the philosophy of death, thousands of these centuries-old literature still exist on the island. Some remain part of furniture at homes, whilst many have been ‘rescued’ by the lontar doctors, ensuring they don’t wither with age or negligence.

The Lontar Museum was a vision shared by the members of desa adat Penaban to store generational manuscripts collected in the vicinity. But the community venture grew beyond the initial gudang, or storage room, plans.

Museum Pustaka Lontar was officially inaugurated in November 2017, acknowledged by lontar maestro Ida I Dewa Gede Catra and Dutch lontar researcher Professor Hinzler, who additionally acts as one of the museum’s curators.

The museum is a series of traditional Balinese buildings dotting over one and a half hectares of highlands in east Bali, enveloped in rolling hills and overlooking fields of green. The village in which the museum if found is locally loved for their lawar jepun, a traditional Balinese dish of minced meat sautéed with vegetables, coconut shavings and herbs. The limited livestock in the district refashioned the popular fare into a plant-based delicacy, using frangipani leaves (jepun) instead of meat.

Today, this library of sorts has become more than just a museum. Housing 313 cakap (volumes of lontar) to date, they have become a place of study, a venue for gatherings, and a ‘clinic’ for lontar— the community caretaker, if you will.

The Balinese view lontar as sacred, carrying traditional knowledge from culinary practices, medicine, agriculture, religious and economic systems to arts, language, and more that all serve as a guidance to conduct one’s life. There are nine categories of lontar in total. Proper care of these items is thus vital for the passing down of generational wisdom. But not all lontars are great in value. The lineup of lontars hung at the museum’s Bale Sang Kul Putih, the centre point of the museum, are everyday notes, not unlike the mundane grocery lists on fridges, or reminders of payable debts, from which you can identify the leaves— dry and written to be eventually disposed of.

“Anyone could write on lontars. They would write them based on experience. For example, one lontar entry recorded how one’s fever was cured with fennel onions, which is categorised under usada or traditional medicine,” manager I Nengah Sudana Wiryawan said, as he invited us to sip the fennel onion tea.

Resembling a rosella tea, the beverage is a ruby-hued herbal drink best served hot for maximum benefits and taste, served to guests upon arrival. It’s been claimed to be of wonders to the skin that the museum’s home-made fennel onion soaps caught the attention of a renowned actress from Jakarta, who bought out their entire supply.

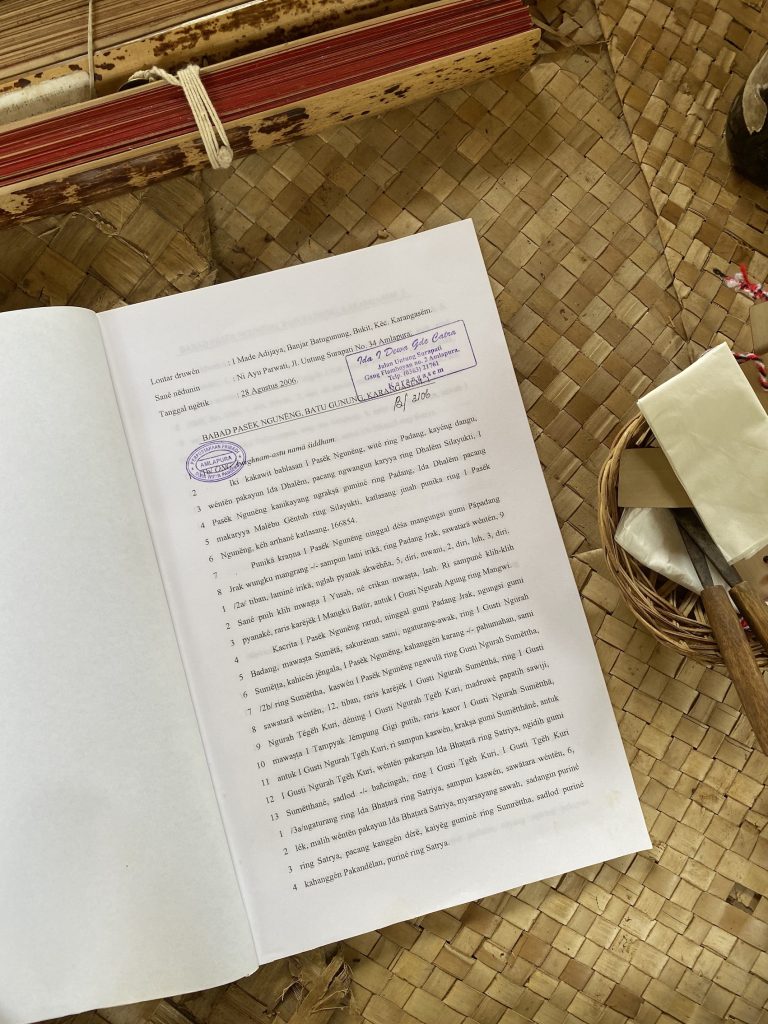

The scriptures you find at the museum are private property, personally owned by members of the Penaban village and surrounding areas. Those who are no longer able to care for their ancestral lontars will deposit them here, where the lontar doctors can properly preserve them. They also help identify and document the collection, noting down the dimensions of each palm leaf, the contents, and the owners. From medicine, mantras, hymns, guides, to various laws and societal norms, they have carefully organised each one for anyone to access and learn from.

“Many have lontar at home but can’t read them, so we provide this essential service of reading and writing. For those who want to bring their lontar for conservation are welcome to do so, too. The team takes good care of them,” Wiryawan said. Some lontar owners don’t allow their sacred scriptures to leave the house but the lontar doctors happily cater to their cautious clients, bringing the clinic to them.

The team has translated a majority of the catalogue into English and Indonesian to break the language barrier and accommodate those who wish to learn more about Balinese culture through traditional literature. With the tools made available by Surakarta University, some of them have also been digitalised. There are 130 lontars accessible online currently. Visitors who seek to read the lontar in its purest form can, too, learn to read Balinese Sanskrit at the clinic.

The clinic, where the doctors work their magic, stands as the cardinal element of the museum. Giving the museum a much deeper purpose than simply exhibiting the manuscripts.

Anyone who is ‘appointed’ or has a calling to progress spiritually into a pemangku is required to study and graduate from the museum before they are ‘trusted’ to hold their first ceremony. There are two divisions of pemangku disciplines: Sang Kul Putih and Kusuma Dewa. Here, the lontars provide an unabridged education of Sang Kul Putih, derived from the teachings of Mpu Sang Kul Putih, a highly-regarded sage from 11th century. Bale Sang Kul Putih, where they hold gatherings, was named after him.

Museum Pustaka Lontar operates on donations and offers visitors an introduction to lontar, including workshops to Balinese Hymns, Lontar Manuscript Making, and Balinese Alphabet, delivered over the expansive coconut plantation, a serene and meditative setting as you put blade to leaf.

You’ll appreciate the literature more as you learn the Balinese would spend up to two years to produce one lontar. And you need to be selective with the leaves; only those from Ental Trees that have a slope of 35 to 40 degrees pass as lontar. There are multiple stages to undergo before the desired paper, called pepesan, is achieved. The final product ready to be written on. From sun-drying, soaking, marinating, boiling, clamping, perforating, and more. The museum team beam with passion as they explain the step-by-step formula of lontar making.

The museum hasn’t reached its last phase of construction due to the pandemic. For this reason, they have refrained from keeping large amounts of lontar, as none of the current buildings offer the right storage standards, in regards to temperature.

Right now they use acid-tight paper containers made by students from Melbourne, who had partaken in workshops last year. They invented these boxes to store the lontar properly whilst the museum focus on finishing the main building. These containers are also termite and insect-proof.

A lot are in the works here at the lontar museum, as they also see a future of building inns for those who come to study for weeks. “More than a museum, we’ll be a retreat for scholars.”