Since the Kamasan era, Balinese art has largely been associated with traditional paintings. Army of ART•BALI and art curator Savitri Sastrawan, beg to differ, expressing how this no longer applies and should be detached from popular belief. We take a look at the development of art on the island from the eyes of these ‘caretakers’ of creativity.

The arrival of Europeans in the 1900s played a part in revolutionising the culture, leaving more cavernous imprints than we may think. Bali has been marketed as ‘paradise’ ever since, which spiked the tourism boom and with it followed ramifications, including in its art culture. Bali is constantly being sold to the world; the early days of George Krause’s photographs introduced the ‘last paradise on Earth’ to the western spectacle and consequently, common identifiers such as ‘traditional’ and ‘exotic’ ensued.

Army, in his twelve years of working in art management, denoted the lack of understanding of the social development that occurred in the 1920s. He thinks the label ‘traditional’ in visual art deserves to be left in the past. It’s no longer the word to accompany Balinese artists. After the long-established Kamasan, Batuan, Pengosekan styles, artists have allowed a transformation in their work and whilst the core values still exist, the narratives and approaches have been reconstructed.

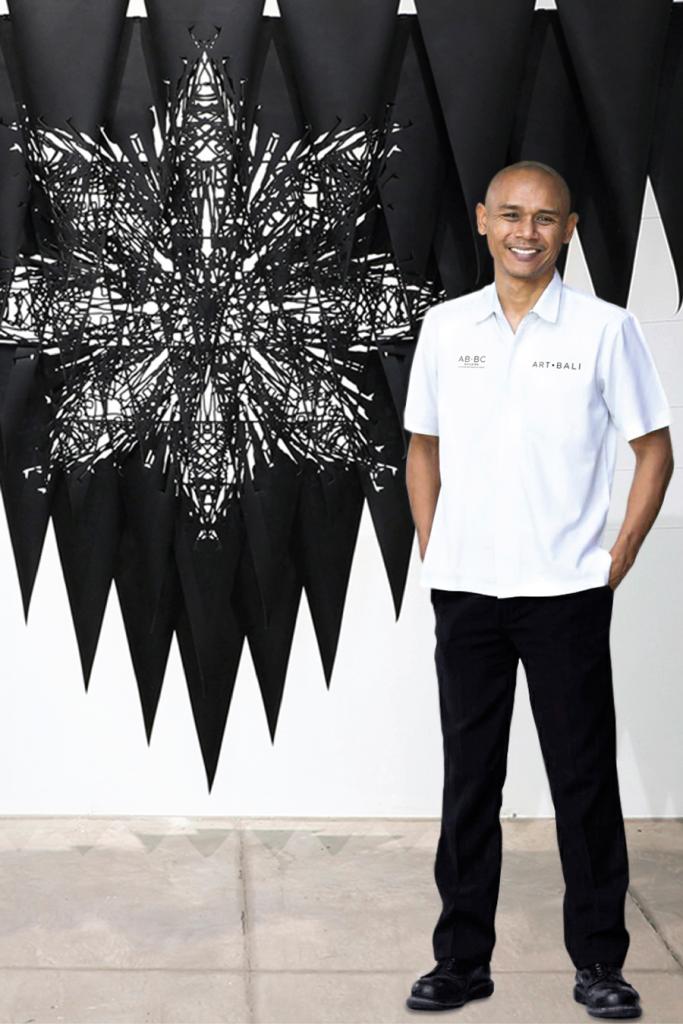

Army is one of the masterminds behind ART • BALI and AB•BC Building, a multifaceted creative space in Nusa Dua, who has a degree in psychology and an eye for art. Art in Bali, he expands, is ultimately an exploration of Balinese-Hinduism — the religion, rituals, and traditions— with the objective to retain a collective memory of the past. For this reason, many look at Balinese art from an anthropological point of view.

“I think that’s one of the issues that is keeping Balinese art from getting more recognition. It’s because there is already that definition that is given. When you see the Kamasan or Batuan paintings, these are the buzzwords linked to ‘traditional Balinese art.’ And there is a mistake in that,” Army said.

Other than ART • BALI, under the art management of HeriPemadManajemen, Army helped to host an exhibition called Balinese Masters just last year. He recalled it to be an interesting sharing of perspective. The development that has been happening in Balinese art is in fact related to modern progress rather than what people see as, fundamentally, traditional art.

Using rerajahan as an example (a prayer in the form of drawings on a piece fo white cloth, not unlike a ‘lucky charm’ for protection, health, and prosperity), it is an authentic religious art piece created and used by priests. An artist who goes by the name Kuncir is famously known to explore this style, though his visualisation incorporates contemporary shapes and visuals than that of its original form.

The different explorations, and relations to current social issues, take effect in Army’s curatorial process. Alongside several questions to inspect.

What is the message we are trying to convey? Is there a specific type of style? Do we want to bring up a new medium that hasn’t been explored in Bali and create something completely new? Who could be the artists who want to explore this new horizon? How do we keep the audience curious and engaged?

“You see a unique quality in each one; in the way each artist explores their style and medium. It’s an output or product of self-expression, and at the end of the day, you cannot really detach from what is going on with the world.”

ART • BALI is an annual interdisciplinary exhibition curated to present the development and ideas of artists in Bali and around the archipelago. With this, plus a spotlight showon Balinese artists, the curator, Rifky Effendy,saw the originality in Balinese paintings that cannot be replicated. It’s in the Balinese-Hindu teachings and social environment, such as ngayah(obligation to work for the village). These experiences contribute to the uniqueness, even down to colouration.

“What I noticed in Balinese artworks, especially the legends, is the colours. If you compare them to those outside Bali, you see a different saturation. The Balinese work around more subdued hues, not vibrant reds and yellows. No one knows why, it just is. It could be something about the way they see colours from their surroundings.”

Balinese curator Savitri Sastrawan has a certain admiration for the innovative art scene, even valid in everyday living. Like Army, she learned to value Balinese art with tendencies for renewed explorations.

For her, the art of curating is procured from her own point of view as an artist, writer, and fine art graduate. Though having been working in curation, she calls herself an arts and language freelancer with a profound interest in cultural and geographical studies.

Before settling back in her homeland, she lived a nomadic journey, spending most of her life in the UK where she pursued her masters degree in global art. Upon returning and gradually immersing in the art culture, she has admired the transformation and innovation that she has seen in her time working with local artists.

“A bunch of artists have already come out of the traditional techniques and innovated new things themselves. Whether in painting or other materials, there’s innovation going on — not limited to the artistic approach but also about the intention of the work, and the delivery. It’s always exciting to see: how far are you going to stick to the old ways and how far are you going to deconstruct them? What’s new about them?”

You’ll find these questions answered within the strokes of her curation, where felt experiences are boldly underlined.

“There is an experience you can bring back, even down to how you place the artwork. You really have to think about what you want the audience to feel, what is the artist’s intention, and how do you bridge that to the audience so it resonates.”

Bali has a deep-rooted culture, she reminds us, but it’s never just about the traditions, as there is always some form of expansion within it. She draws an example from the pre-Nyepi ritual, ogoh-ogoh, which hadn’t always existed. Year by year, the ritual of going around chasing bad spirits away with fire integrated into a festival that showcases the younger generation’s creativity. Still, the core idea remains fully intact.

The new vogue that is easily spotted are the owl kites, locally known as celepuk. People turn to artists to design them — and to Savitri, this is an example the common art scene that often goes unnoticed. When things pop up outside the confines of an art space but in society.

Army would concur. Whilst his interest in art changes over time, recently, his attention has been diverted to public art. The monuments and statues placed in the middle of a roundabout, or tucked between a junction. He sees it as something that the public can engage with but still fails to. Outside of formal education, most are still out of touch with art, in comparison to other creative forms such as music. When in reality it is actually one of the most tangible forms.

“It’s actually everywhere. You rarely find parks for the public or for families to enjoy time outside the house. But for instance, when you come out of the airport, you see a statue of Arjuna by the junction and at night people would just hang out there.”

“It’s a great idea. People can access it, people can get close to it, it interests them, and that’s a good start.”

The most common ones you see growing up are tigers, dragons, police officers, historical figures. There’s so many ways to educate and correspondingly bring people closer to art.

When art is omnipresent, what we do is strengthen its preservation. The curators see it as an understanding of what they are presenting; whether it’s the information or the development. Art is limitless — there are many ways to explore the definition of Balinese art. Then comes the appreciation of the art, which comes back to us, the consumers.

Army strives to break the boundaries surrounding the consumption of art to reach more diverse eyes and ears, which he does with AB•BC Building ‘in the little things.’ They have been working with schools and social communities. Working with Ketemu Project, for the last ART • BALI exhibition they invited the blind to the exhibitions that coincidentally had artworks that were perceptible by touch. They invited a hearing impaired audience and hired interpreters. Because everyone can and should appreciate art.

Savitri, on the other hand, is rejoicing in art archives at her current employment, Danes Art Veranda. The difficulties finding references from local perspectives are still remarkable, so she created a podcast to translate and preserve these records into virtual experiences. Decades worth of rich history and knowledge that otherwise would have remained as the island’s best kept secrets.