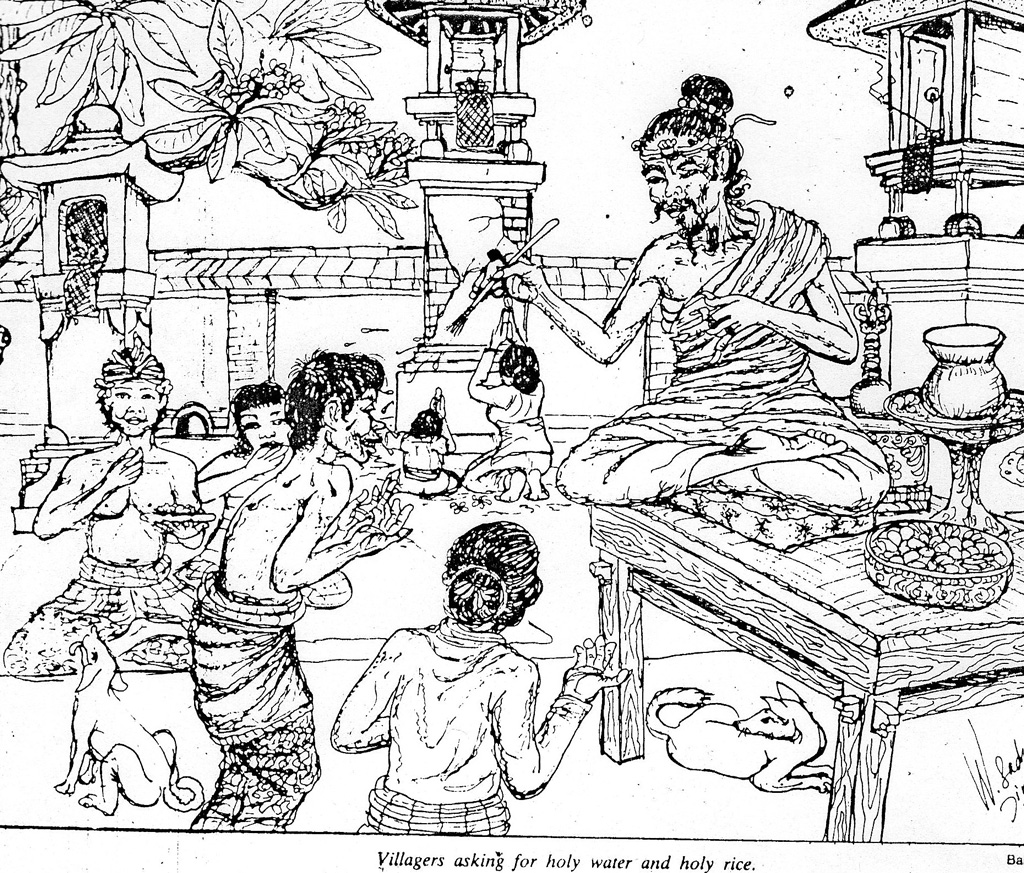

When Westerners think of Balinese priesthood, they are usually awed and, accordingly, embarrassed by “excessive respect”. It must be said that the view of a pedanda priest, lotus-sitting on his platform and jingling his genta bell to call down the gods to the rite he is performing, is highly impressive and calls for spontaneous respect. Imagine yourself with the Pope at Saint Peters. Not the kind of scene one easily makes fun of. So, when you see a priest, his little bun in the back of the neck, walking slowly between two rows of bowing faithfuls, you don’t feel you may heckle him.

You may not because you are a Westerner. Not many Westerners, staunch admirers of secularism in their country of origin, become fanatical supporters of the dominant social state of affairs in Bali – especially with the Brahmin priests at the top of the social order. They are ready to swallow anything in the name of tolerance and thus don’t hesitate to become reactionary in order to appear progressive.

Yet, it would be a mistake to think that all Balinese concur and let themselves get caught up in the game. For a number of reasons.

First, not all Balinese acknowledge the superiority of the Brahmins, and more generally of the Balinese “caste system”. To quite of few of them, the Majapahit court culture that was introduced to Bali in the wake of the 1343 Javanese invasion remains alien. There are many villages across the island in which high-caste people may not become residents unless they give up their caste status. Furthermore, on account of the inroads of a religious reformism hued with “democratic” ideas, most of the modern Balinese don’t think regard the high-priests (the twice-born dwijati) have to be from Brahmin’s lineage. In the last 50 years new types of high-priests of satria and sudra origin have thus appeared as the virtual equals of Brahmin priests: the rsi, empu, begawan etc. They too may now prepare the holy waters needed for completion of the highest ceremonies (big cremations, big exorcisms, etc) of their respective kinship groups. Balinese religion is in fact far from being cohesive. It might be classified as a “religion”–and have us think that the beliefs, gods and rites are structured as a cohesive whole, but it is far from being the case.

Back to the Brahmins, mockery and irony is more often the rule than not. According to the principles enshrined in the manuscripts of which they were long supposed to be the exclusive guardians, the Brahmin priests are “twice-born”, i.e. they were born again upon priesthood as perfectly “pure”, impervious to sexual desire and greed. This is indeed not always the case, and there is no lack of generous souls to underline it:

Thus one of the most famous characters of the Balinese classical literature is the Pedanda Baka: a predator “bird” who dressed as a priest to wreak havoc in a fish pool. Looking like a holy man, he goads the fish to come out in the open; when they do, he eats them all. The story tells implicitly that “clothes do not make the man,” and that high-priests can indeed behave improperly.

Yet, it is the priest’s sexual behaviour that is most often the object of people’s mockery. The priests normally enter priesthood beyond the age of optimum sexual urge, and their induction to priesthood, priests are supposed to take them beyond sexual desire. But stories of high priest having no control over their “priesthood stick” (tungked) are numerous. Criticism is most often formulated through sarcastic innuendos. People will refer to a story, for example that of the “Lubak Jenggot”. No name will be uttered, no mention will be made of the protagonist as a priest. But everyone will understand: the lubak is the mongoose, a small animal that is able to penetrate any hole; as for jenggot, it is the beard. The reference is clear: lubricious or not, high priests let their beard grow. In the actual story, the lustful priest is trapped when he is getting into the act, and those who catch him grime him with black coal and take him around the village streets, where the villagers heckle him in the open:”bearded mongoose, bearded mongoose. Shame. Shame on you”. A few more hidden reference and people understand which high priest, in real life, is thus being mocked. Let us say: “the one from beyond the river, who likes to be massaged by a beautiful servant woman from the village over there”. Everyone understands. Stories thus travel, sometimes true, sometimes not. But always damning. “Smoke cannot be hidden, “ as the saying goes.

Stories abound. The most common are not directly against high priests directly, but against their whole household (gria). Among its inhabitants live women who specialise in the preparation of offerings for the highest rituals and they have their own ways to let the faithful know that the price of this or that set of offerings should not be too cheap. In this case, criticism is less acute: with modernity, many people want to see their priest as well off as themselves.

Usually, even when names are not uttered, people pinpoint someone, always indirectly, while hushing all the same. Among the stories that came to my ear, one is about a Brahmin who was at the head of one of the regions of the island. As it sometimes unavoidably happens, he mixes up his own bank account with that of the area under his guidance. He was aware of his misdeeds. And thus knew he was going to be sued when the investigations would be over. So, what did he do? He found a nabe to be his sponsor and quickly became a priest. Because traditionally high-priests are beyond the arm of the law. Well done, isn’t it? If the story is true.

Does it mean that we should have a negative opinion of Balinese priesthood. No. Criticism in Bali is usually done through layered stories. Its purpose is not so much to condemn and to expose, than to educate.

Anyway, it remains probably easier to criticise priesthood in Bali than in other parts of the world – and of the country.