You can listen to a full interview with Bali 1928 in Episodes 23 and 24 of The NOW! Bali Podcast:

“I haven’t heard this since I was a kid,” said Wayan Beratha upon hearing the scratchy recordings of a Balinese gamelan composition from 1928. The melodic tones of Curik Ngaras (Starlings Kissing) sparked a 70-year flashback in the elderly Balinese composer, bringing with it a jolt of his youthful inspiration. A week later he had taught the composition to the children’s gamelan in his village, thus reviving a piece that had been long-forgotten, frozen in time on the dusty shelves of UCLA.

Witnessing this unexpected outcome, how a re-jogged memory could result in a musical revival, Edward Herbst made it his new mission to repatriate these early twentieth-century recordings of music in Bali.

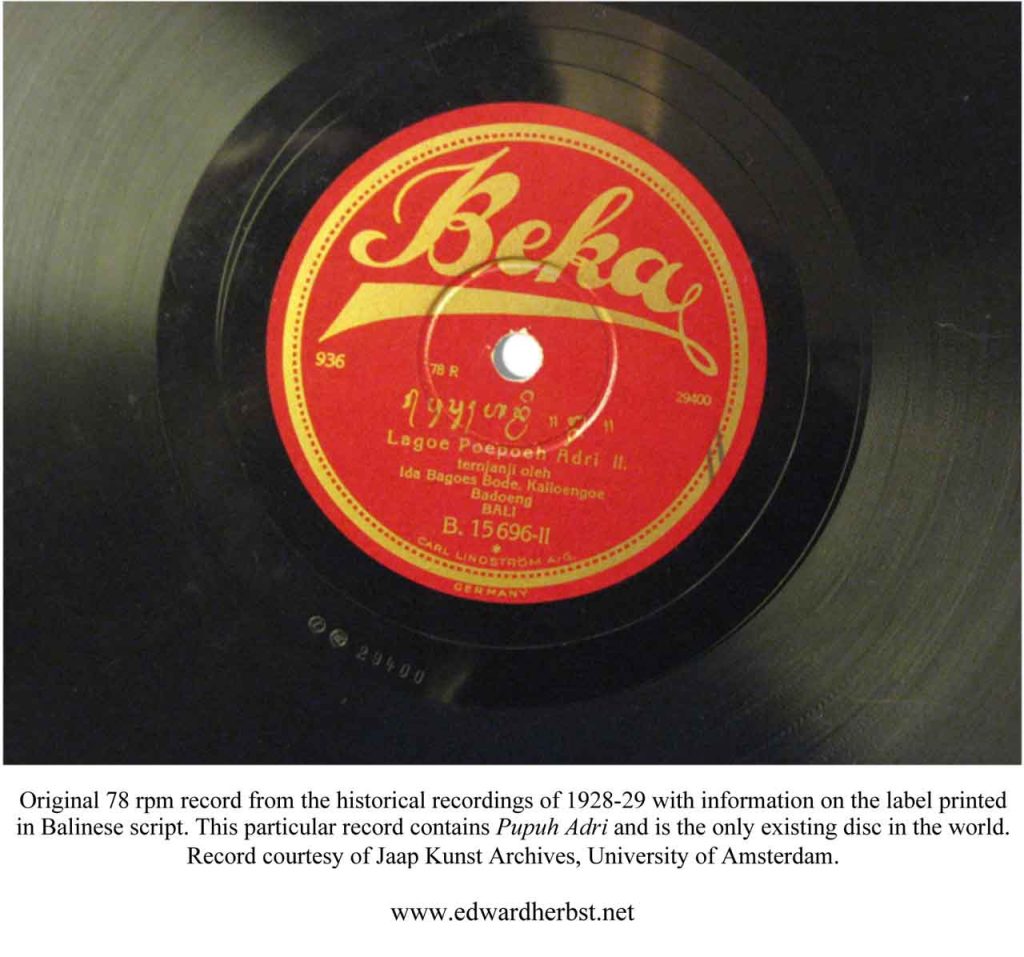

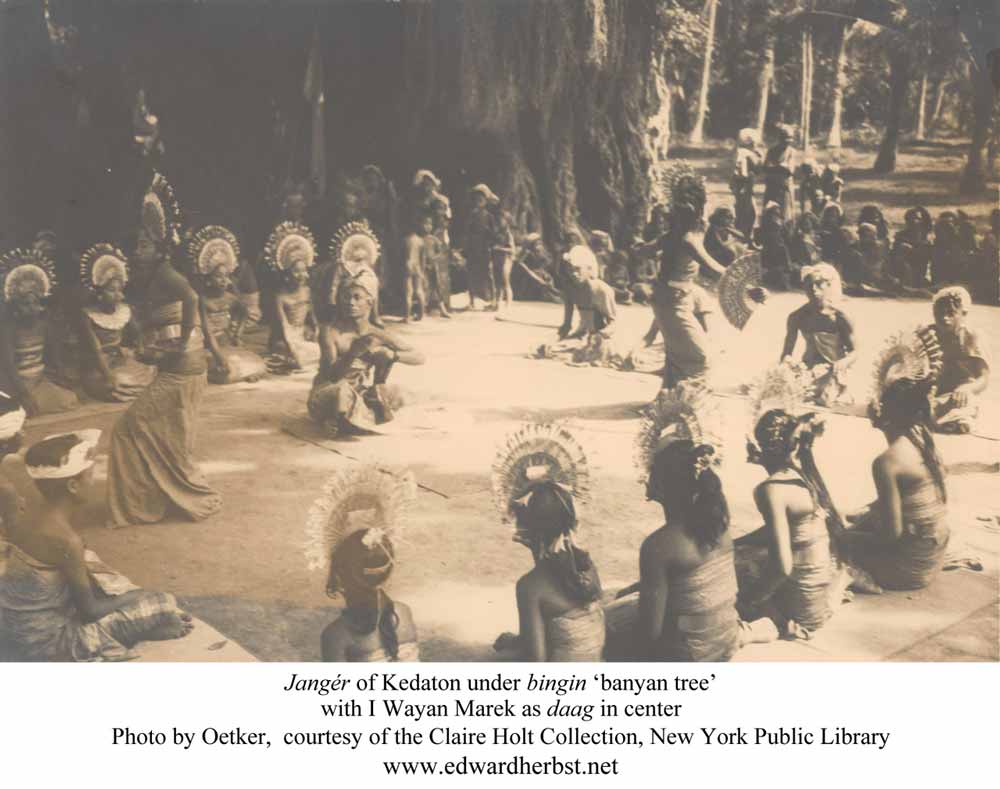

Officially starting in 2003, Bali 1928 has been an on-going, international and interdisciplinary project to bring pieces of Bali’s musical history back home. The name of the project comes from the year that Odeon and Beka (better known today as Odeon Recordings) produced shellac recordings of Balinese music. Engraved into the wax of these shellac 78-rpm records are the earliest recordings of Balinese music; the remaining 56 surviving records (111 sides) have now been repatriated and archived by Bali 1928, alongside a rich collection of 1930s films, photographs, publications and memorabilia.

What’s special about Bali 1928 is that it is no ordinary archiving or repatriation project. It is run independently, powered by the passion of its volunteers and project managers, not for some national agenda, but really for the good of Balinese communities.

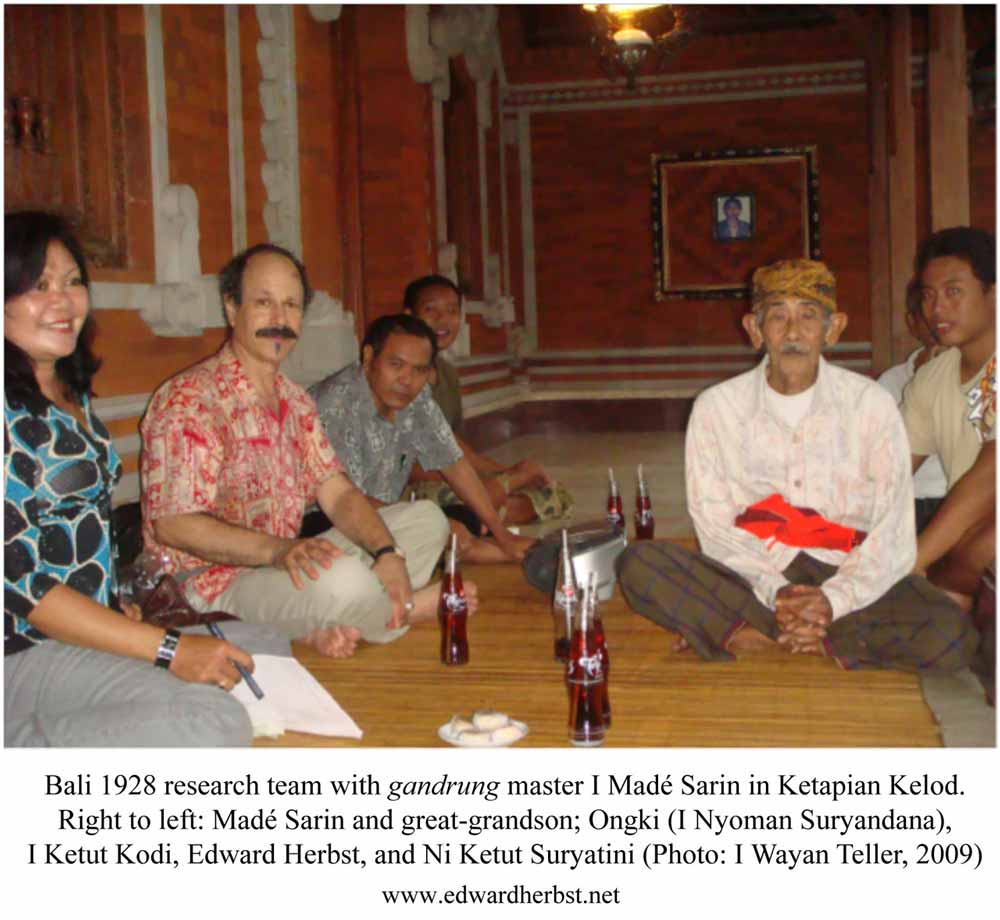

“The question is to whom are we repatriating these archives?” explains Edward Herbst, the American ethnomusicologist who began this monumental project 20 years ago. “This has been a repatriation of the memories and knowledge of that oldest generation in Bali.” To return recorded memories to those who never even knew such a thing existed has been a driving motivation of the project, but in the process of that, the effects of introducing these histories to local Balinese communities has had unexpected effects, causing ripples of change in social, artistic and even environmental circles now ‘awakened’ by the visions and sounds of the past.

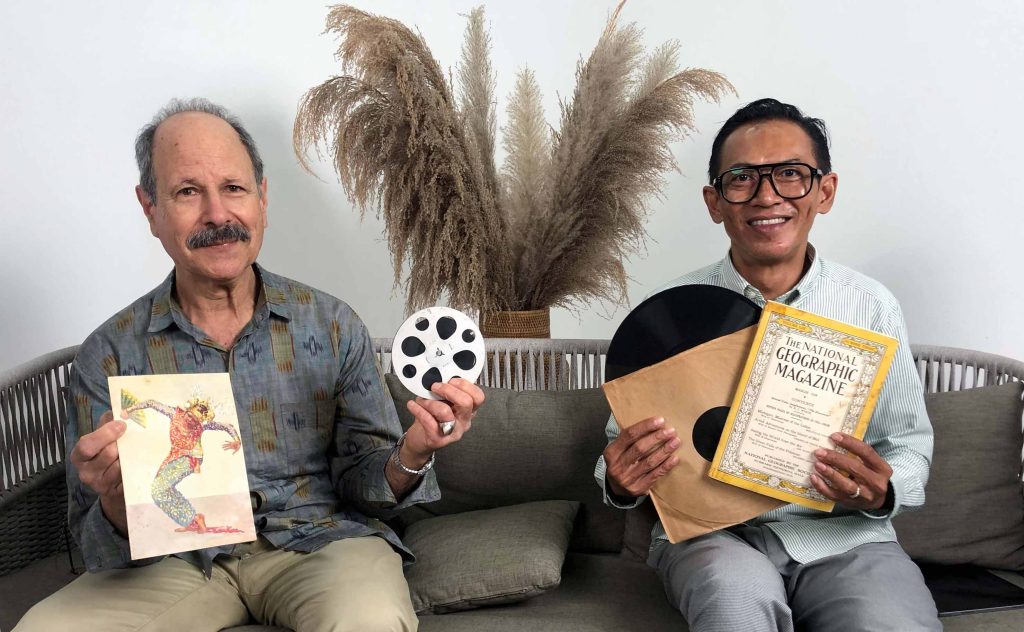

Edward Herbst (project director) and Marlowe Bandem (project manager) share how Bali 1928 unfolded and developed over the many years, and just how meaningful the project really is.

Re-Memory

Balinese music has been a lifelong passion for Edward Herbst, who first spent 12 months on the island in 1972 for independent study, returning again in 1980 which resulted in a Ph.D. in Ethnomusicology from Wesleyan University. He then published a book, ‘Voices in Bali: Energies and Perceptions in Vocal Music and Dance Theater’.

It was through these years that Edward grew to know I Made Bandem, the father of Marlowe Bandem and a renowned figure in Balinese performing arts. He too received a PhD in Ethnomusicology from Wesleyan University (one of the first Balinese dancers to study in the US), and is one of the founding fathers of the Bali Arts Festival.

Funnily enough, it wasn’t these two scholars that caused the initial spark for Bali 1928, it was the echoes of gamelan itself that willed this project into existence.

A musicologist and audio restorer in New York, Allan Evans, was listening to a radio program on the principal music researcher of Bali, Colin McPhee, during which a recording of gamelan was played. Allan noticed that the sounds of this strange orchestra reminded him of Claude Debussy or Steve Reich, both of whom were influenced by the gamelan orchestra. Consumed by curiosity, Evans began locating and archiving these old recordings and got in touch with Edward Herbst, by then recognised for his knowledge of Balinese music, to help categorise, research and make CD notes of these archives.

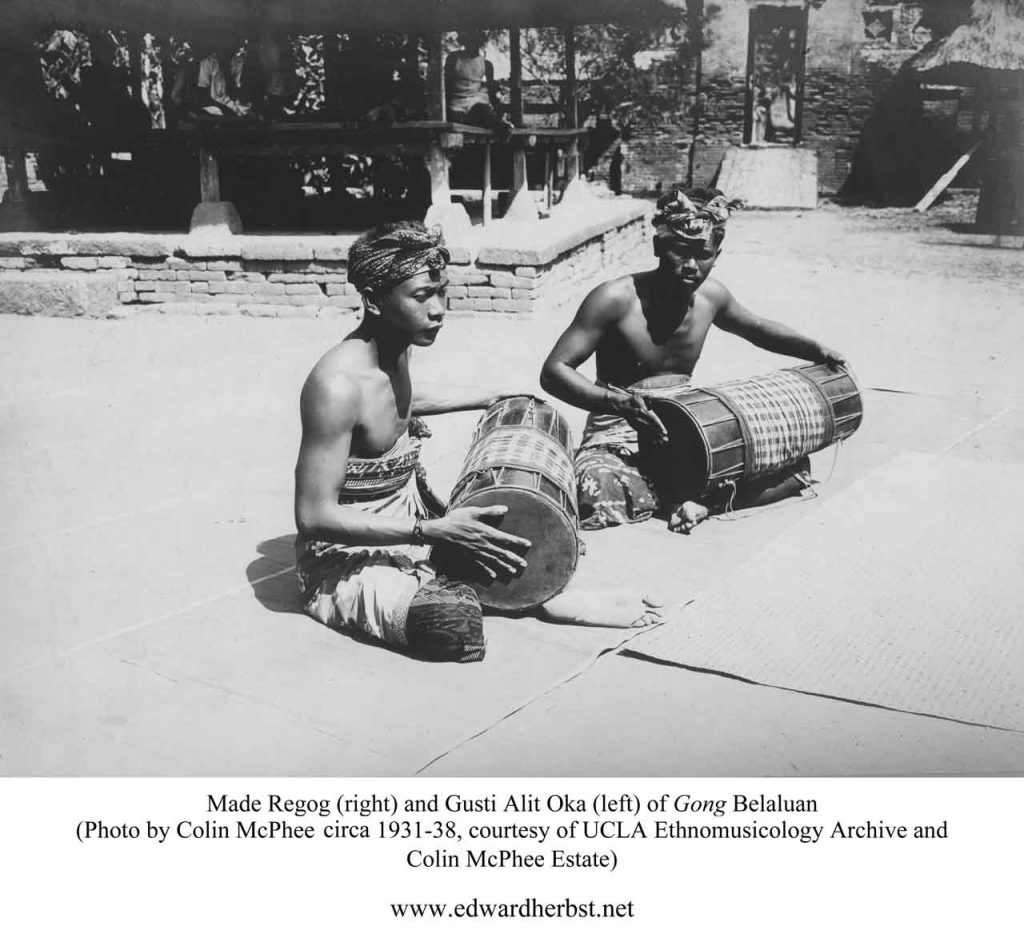

Edward’s research brought him to I Wayan Beratha in 2000, a Balinese composer and the son of I Made Regog, also a composer who made many of the compositions in the 1920s and 30s. It was during this encounter, upon playing these old cassettes to Beratha, deeply moved by a sense of nostalgia, did Edward realise that these recordings were more than just archives.

This feeling was compounded by a similar story: Nyoman Rembang from the village of Sesetan was played a Gambuh ensemble (dance-drama) recording and said to Edward, “I haven’t heard this since I was six years old…” When the Japanese occupied Bali during the war, many villages buried their musical instruments so they wouldn’t be taken away. In Sesetan, after years of occupation and revolution, the tradition was never revived. essentially wiping out the tradition. Now it could be remembered, and thus revived.

So, upon his return to the US, Edward and Allan agreed that repatriation was the new goal, to return the memories of the Balinese back to the Balinese. With the help of other collaborators – Philip Yampolsky, Andrew Toth – they were able to locate and recover all the known original recordings from the late 1920s, restored by Allan Evans.

A Thousand Words

The Odeon-Beka musical archives record an important part of Balinese history. At the time, Bali was going through a musical renaissance. After the great Puputan battles against the Dutch colonial government, the Puri, or royal courts, could no longer play their role as the patrons of arts and culture. Thus, gamelan sets were given to the villages and musical composition was democratised, resulting in a blooming of new gamelan styles, such as the kebyar, the most common style today.

“I make the comparison of the first written account of kebyar in 1914 in north Bali to the first jazz recordings by Nick LaRocca of the Original Dixieland Jass Band in 1917,” remarks Marlowe Bandem, highlighting the historical significance of these two moments.

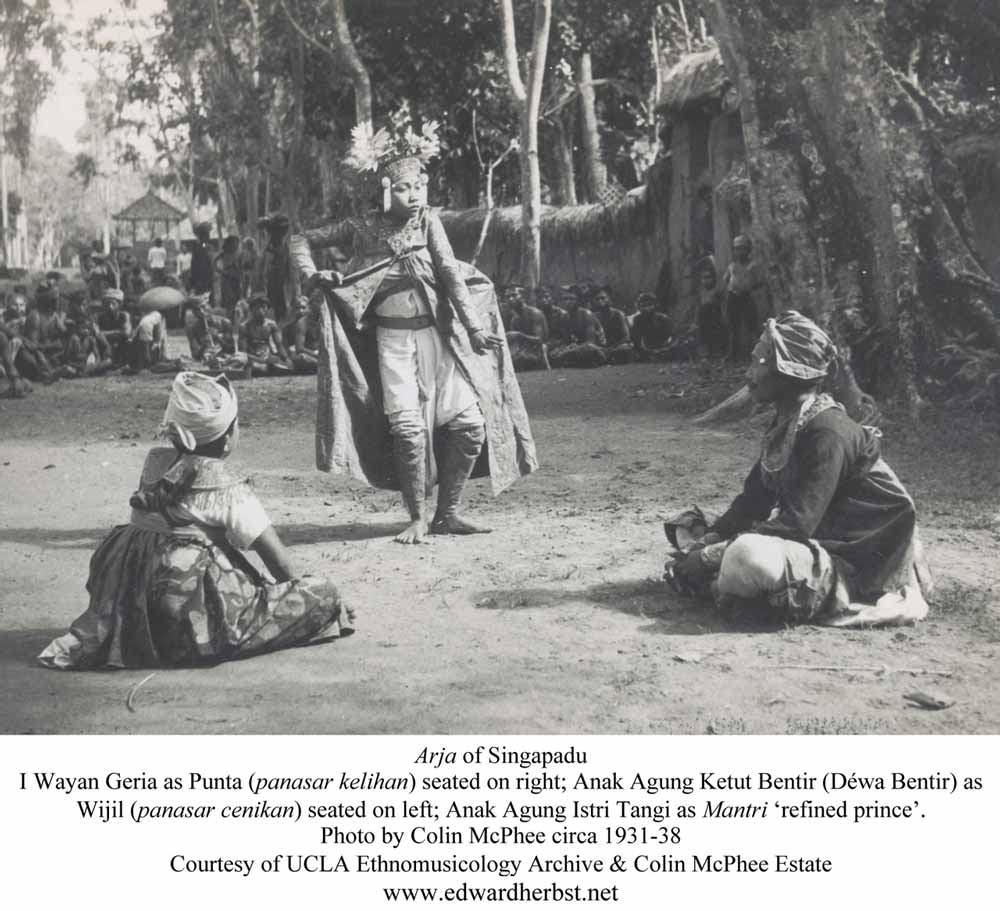

It was also these recordings that spurred Colin McPhee and wife Jane Belo to visit Bali from 1931 to 1938, which became a period of prolific writing, filming and studying of Balinese culture. This resulted in McPhee’s books Music in Bali and A House in Bali. Alongside the likes of Margaret Mead, George Bateson, Walter Spies, Gregor Krauss and of course Miguel Covarrubias, their collective works – the photographs, films, paintings, stories – put Bali on the map to the outside world.

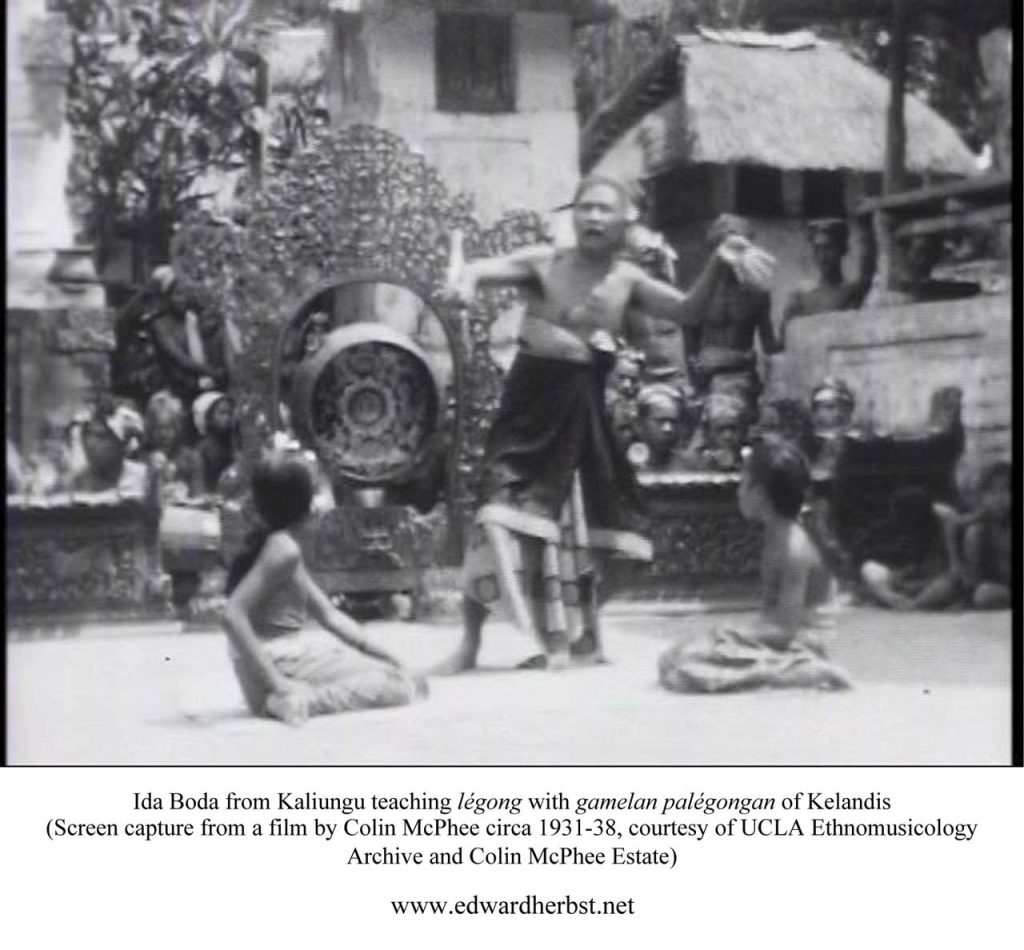

“Ed, have you seen the McPhee films?” asked a UCLA archivist as Herbst was leaving for the day. “I said ‘What? McPhee films?’ So I played the DVD and made a wild guess that the legong dance teacher was Ida Boda, and I flipped. I literally lost my wits.” UCLA had McPhee’s entire film collection of Bali, which only came to Edward’s awareness in 2009 when they were digitised. This opened a whole new paradigm to the Bali 1928 archives, where music, silent films and old photographs could be cross-referenced, people identified and new histories recorded. The films of Miguel Covarrubias and Rolf de Maré were later added to the collection. This rich tapestry of documentation, weaved together by the 1928 team, brought the past to life for today’s generation.

Bali 1928, in the 21st Century

“The early twentieth century was a time of discovery. It was at that time we saw the birth of the kebyar, a new style of playing gamelan in Bali. As a Balinese, what motivates me is being able to unearth, rediscover and provide questions on how such legacies keep changing through the continuity of time,” shares Marlowe Bandem, a vinyl-DJ whose vinyl collection now expands to historical gamelan on top of his usual repertoire of classic deep house music.

Marlowe joined the project in 2013, bringing his background in micro-banking to provide a sense of management and overall structure, whilst assisting in the cross-cultural communications as a Balinese. His most pivotal role was to ‘transpose’ the archives into the digital world, using modern tools to scale up their community-based collaboration and feedback so essential to validating and referencing a lot of the documentation — and identifying those seen in the footage.

Prior to going online, this community-repatriation was done through site-visits, where the Bali 1928 team would go to specific areas and present the archives to villages, hamlets, schools and universities. They even did a roadshow called ‘Sinema Bali 1928’, using a mobile cinema to play movies in rural areas.

“All of these historical documentation should be returned to the place where they originated, because it relates to the identity and the cultural legacy of the place,” states Marlowe. These visits would often yield even more information, uncovering the collective memories of the Balinese that add weight to the research and archives, tying stories together, improving the wealth of the material. It has become a truly collective, grass-roots initiative that involves the entire island.

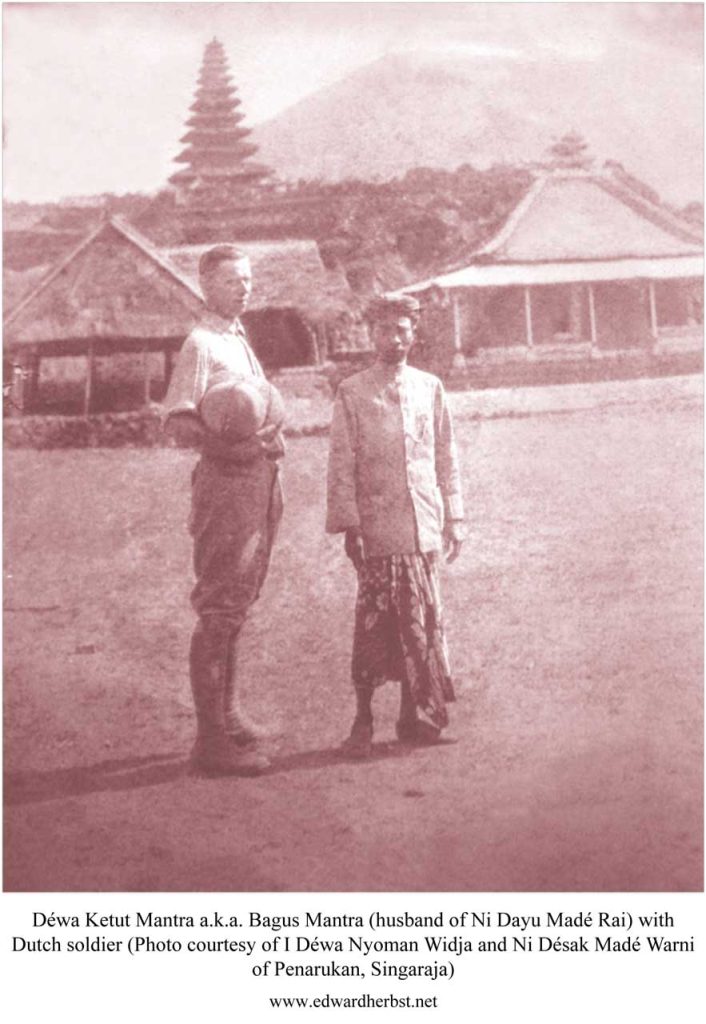

“For example,” shares Edward, “we did a seminar in University Udayana where we were discussing the performances of Ni Dayu Made Rai and played four old tracks of her singing. At the end of the talk, a hand went up in the back and a young man said to us, ‘I can give you more information about my grandmother if you’re interested?’ It was Ni Dayu’s grandson.”

This is one example among hundreds over the two decades, scaled further by the use of social media and the internet in their communications. Using the documentation, Bali 1928 set up discussions, focus groups, photo exhibitions, live shows and more that become a basis for dialogue on ethics, history, and society for both young and old Balinese.

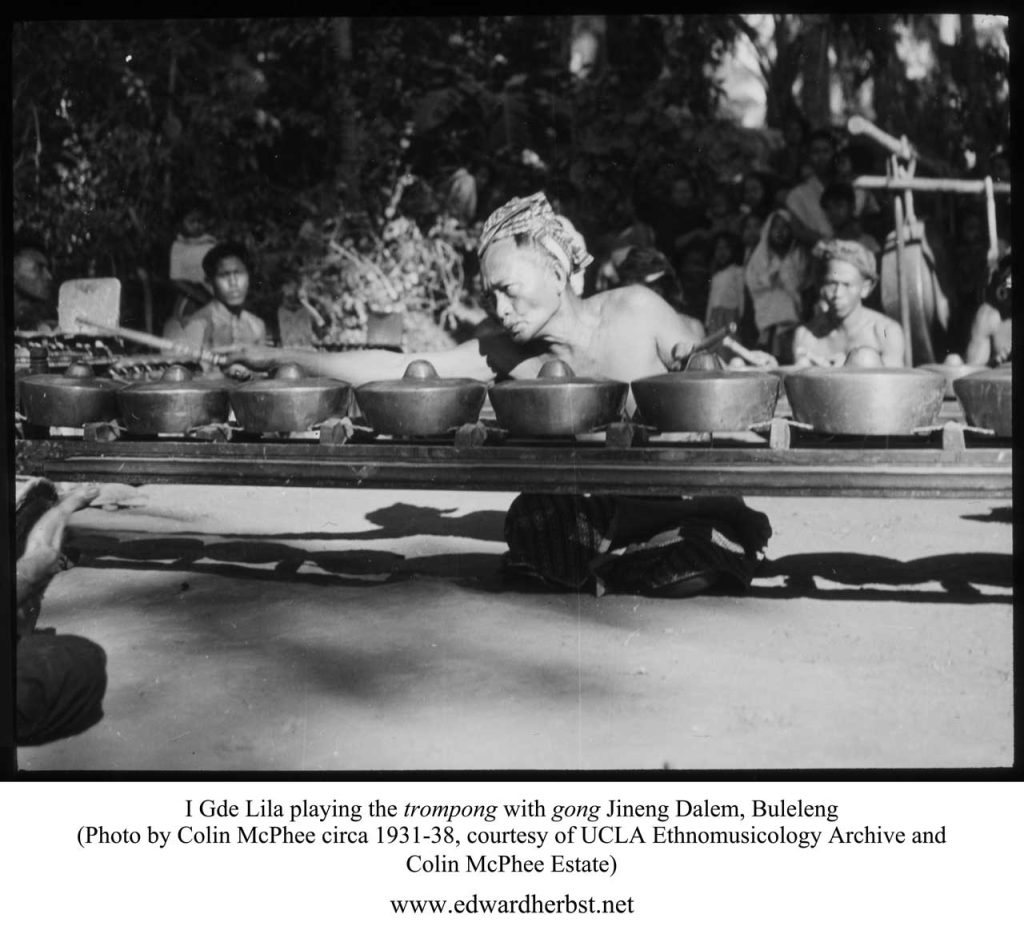

The emotional and moral benefits of repatriating these recordings to the old generations was clear from the beginning: families given photographs of their own grandparents which they had never had, memories made tangible and visible once again. A video of a north Bali trompong dancer, Gde Lila, was shown to his son (already in his late 90’s), who watched and stared in absolute disbelief, and said under his breath, “…Bapa…” or “…Dad…” as he recognised the vibrant figure on screen.

Edward and Marlowe shared the surprising effects this footage and recordings has had on the younger generation, too.

For today’s sekaa, or performance groups, they are able to trace the beginnings of a style or form. To analyse the evolution of compositions and choreographies, notice what was removed or added over the years — bypassing 80 years of constantly transforming arts and go straight to the ‘source’. As a result, theatre communities have already made new forms of contemporary art, basing their creations on original forms, as well as reviving traditions long forgotten.

An unforeseen side-effect of Bali 1928 has been the archive’s use by environmental groups. They utilise the footage to show today’s generation just how pristine Bali was before, to give context to the radical changes their island has undergone over the decades. “It’s a platform for the younger generation to become more critical of development in Bali,” says Marlowe.

“There are young Balinese who wonder, ‘What was the world and environment of our forefathers like?’ and McPhee’s truly ethnographic films from the time allow today’s generations to really witness that,” adds Edward.

The Next Chapter

The work goes on for Bali 1928: community-based repatriation continues to add substance and potency to the archives, and the influence of their presentations spread to more people.

Edward Herbst will be publishing a comprehensive book that outlines their work so far, analysing the recordings, films and the knowledge of the community, supplemented with audio and visual media.

With much of the previous works being centred on the original Odeon-Beka recordings, and Colin McPhee, Covarrubias and Rolf de Maré footage, the next ‘phase’ focuses on the documentation done by anthropologists Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead from 1936-39, with 10 hours of footage and thousands of photographs that expand the scope beyond the arts and open up discussion on ceremony, life cycles and society in Bali. Also the work of McPhee’s wife, anthropologist Jane Belo, whose work focused on Bali’s sacred trance dance’s specifically.

The work of Bali 1928 is significant in many ways. The past, the history, the memories and even the sense of nostalgia that this documentation brings forth has the power to influence the sense of identity of today’s Balinese. It strengthens the very roots, the akar, of their being. The past is not dead because legacies live on, and as a consequence the past has the ability to shape the future of the island.

Find out more about Bali 1928

Indonesian Website: bali1928.net

English Website: edwardherbst.net