With respect to the small Protestant community of Bali, the title is not a joke. Because we may be witnessing a uniquely Balinese variation of what happened five hundred years ago in Europe with the Protestant Reformation…

What did happen five hundred years ago in Europe? Not much at first, except that some people started reading the holy books of Christianity, the Bible and the New Testament on their own. Before then, only some men of letters, mostly priests and monks, were knowledgeable enough to understand – or guess – all that was proclaimed in these holy books. Since they had a monopoly of interpretation they could invent meanings that pleased their purposes. By the late 15th century, the highest of all priests, the Catholic Pope, had decided that the best way to gain access to heaven was by purchasing ‘indulgences’. The more money you gave, the easier it was to go to heaven. Great, wasn’t it?

Alas, the world was changing. Up there in the North, in Germany, a fellow had invented a ‘machine’ that could print. His machine was changing the way people thought. Why? Because people could now read the holy texts themselves. With a printed version of the Bible, there was no need to go to the priest to be told what to think about it. One could interpret it on one’s own.

To be frank, at first, the results were disastrous. Fifty years after the printing machine was discovered, the Jews and Muslims were expelled from Spain. Twenty-five years later, a ‘crazy’ monk, Martin Luther, published 95 theses criticising the Catholic Church for their practice of selling ‘indulgences’. Pandora’s box had been opened. There ensued wars and pogroms. After much blood had been spilled over variations on the Christian theme, the personal interpretation of the holy Bible came to final fruition through the systematic questioning of two philosophers, Descartes and Spinoza. The Enlightenment was on….

Now, how does this relate to Bali? The situation is indeed a little different. Let’s examine the Balinese difference.

Bali has had a complete caste system since the 16th century. These castes have long and highly respected lineages of brahmanas (priests), of satria (warriors), and of commoners. The satria lineages all go back to the takeover of Bali by invaders from Majapahit Java in 1343. The origin of the brahmanas is more recent. According to tradition, it dates back to the arrival on Bali in the 16th century of two high priests, eager to escape the quickly Islamising Java. One was a Siwa high-priest, Dang Hyang Nirartha, the other a Buda* high-priest, Dang Hyang Astapaka.

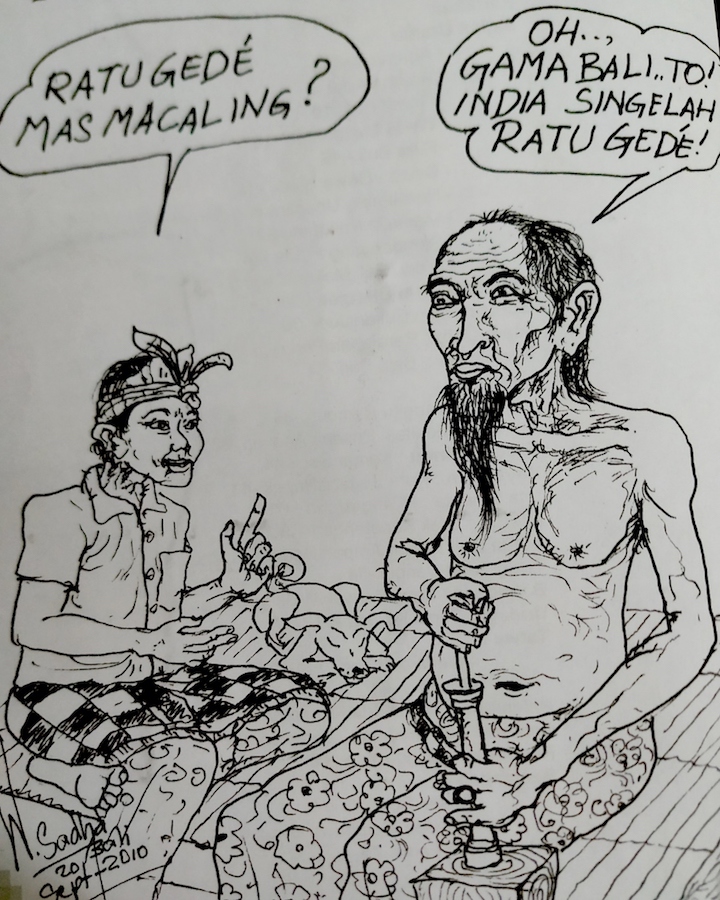

“He is a god from Balinese religion. In India they dont know such god.”

Illustration by Wayan Sadha, 2010

Once in Bali they won the support of King Waturenggong and commenced religious reforms that ensured their preeminence over indigenous priests. They also established their own lineages – Siwa and Buda — which begot all the priests today known as pedandas. These Siwa and Buda priests still officiate (puput = finalise) at all the great rituals, uttering the mantras that produce the holiest of the holy waters (tirta).

Their pedanda position warrants them the highest prestige. They live in large gria mansions, amid an array of mostly ‘commoner’ sisia disciples, thus enjoying a power that almost equates to that of the ruling princes. All the kings of the past indeed had their court pedanda, whose advice and mantras added an aura of sacredness to their politics. Yet, the beliefs and teachings of those pedandas were not only weirdly structured, mixing the Balinese ancestors’ cult with Indian myths and cosmological speculations, but they were also purposely esoteric, which kept them out of reach of ordinary ‘sudra’ commoners.

Then came colonisation, bringing the collapse of the old political order and domination by non-Balinese, but also bringing education. With education came new ideas: progress, democracy, and liberty. And, in their wake, the rediscovery of Mother India, with which all links had been cut since the 16th century*. It is then that the Balinese intellectuals had a big surprise: they found that their traditional weda were mere mantras, and not the “real” veda. Of course, if one reads the “real” vedas, they describe a social new classification system: one becomes a Brahmin if one holds a job linked to spirituality, a Ksatrya if one’s work is to protect the people; a Waisya if one is a trader, and a Sudra if one is an ordinary worker. But it is stated nowhere that one becomes a Brahmin, Ksatria or Sudra by birth.

These “revelations” were a godsend for progressive Balinese intellectuals. So the real Vedas were democratic! Amazing! There were no castes! If in Bali the local brahmana and satria aristocrats claim that they are entitled to inherited privileges, it means that they don’t practice “real” Hinduism. This had to change, they thought. Balinese religion should be reshaped to be in accordance with the newly discovered canonic text.

Balinese echoes of what Martin Luther did with the Bible 500 years ago in Europe when he unwittingly invented Protestantism.

The first thing was to revise history, so serious Balinese intellectuals said that when the Javanese invaded Bali in 1343, they pushed back into the mountain the previously ruling aristocrats and priests. They soon replaced these old rulers with their own new ruling classes, the satria and brahmana lineages (wangsa) of today’s Bali. This meant that the proud brahmanas and satrias of the pre-colonial years were, effectively, usurpers. They had no more right to become high priests and rulers than anyone else.

Having thus reread the caste system with the help of the Veda, and having revised history, our progressive intellectuals had now to transform reality. This took place following independence, after the highest satria lineages, that of the kings, had lost forever their right to rule. Before long, activists from commoners’ clans claimed that, having disposed of the satria kings, they likewise did not need the brahmanas high-priests to run their greatest ceremonies. They had their own holy men who could undertake all the rites requested and thus become high-priests for their own clan. And they soon put that into practice. The first to actually do so was a member of the pasek clan, who was ordained as a Sri Empu in 1952. Others soon followed, representing all the main clans of the island, until each clan had its own type of high-priest: Sri Empu, Bhujangga, Resi, Bhagawan, Dukuh, etc.

This means that there are now two types of high priests, the new, reformed ones whose legitimacy rests on ideal Indian references and clan peculiarities. Whereas the legitimacy of the traditional high-caste brahmana priests – the pedanda Siwa and pedanda Buda – rests on the role they have held for several centuries, and on the magical powers that naturally ensue.

At the beginning of the post-independence period, issues of caste and priesthood were not the most urgent. Hinduism had to organise and obtain recognition from the Indonesian government (1958). So the reformed and the traditional wings of Balinese Hinduism set aside their differences and cohabited within the same Hindu Affairs Society, the Parisada. But with time, the sisia (following) of traditional brahmana houses started shrinking, as educated people tended to affiliate with the new commoner priests. Inevitably tensions occurred more frequently and the two groups split.

But it was only an organisational split. Even today the two groups of priests may ‘steal’ one another’s followers, but there has been no genuine societal and theological split. The priests’ function next to one another, sometimes ignoring one another, at other times collaborating for island-wide ceremonies. Furthermore, the two types of priest have often similar looks, with hair buns and tiaras, which sets them up well above the fray, as if truly twice born. Last but not least, they don’t interfere in ordinary rites, which are the realm of pemangku temple priests and balian medium priests. The high-priests deal with the ‘cosmological’ aspects of Balinese religion, that of the Hindu gods, which have little to do with the ancestors’ cult at the core of Balinese religious practice.

Anyway, history is still present. A brahmana friend recently told me about the ‘new’ commoner priests. He said, “If they want to become high-priests, let them do it. In any case, when they are ordained, or when they prepare holy water, they cannot make do without replicating the rituals and repeating the mantras we created centuries ago. If they can make holy water, it is because of us.”

Thus the Balinese don’t curse one another with fatwas or papal bulls, and no holy war has been declared between reformers and traditionalists. They fight using holy water, and argue with humour. In the long run, both traditions – the modern and the old – will probably mingle within one another in an ongoing process of syncretisation. The God Rama from India will continue coexisting without problem with the ‘god of the river’ nearby. Why? Because in Bali it is not ‘believing’ that matters, it is ‘doing’ what is good and proper. Karma is more important than truth.

In conclusion, despite the differences that have come to being, no, the Balinese are definitely not turning into Hindu-Protestants!

Footnotes:

* It followed the fall of the Vijayanagara empire in the Dekkan (1565) and the subsequent islamisation of all trade in the Indian Ocean.

** Buda high-priests use Buddhist mantras and literary references within the mainly Shivaist system.